Seven months of moon mission training has brought spaceflight “much closer than it’s ever felt before,” according to a Canadian astronaut.

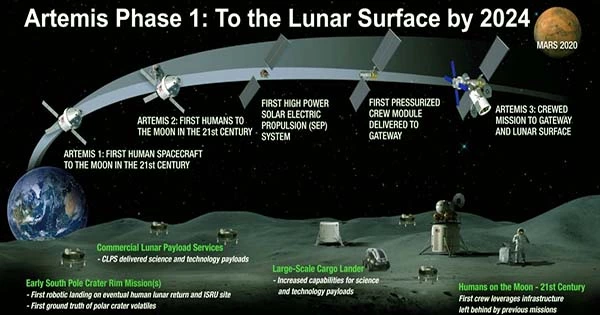

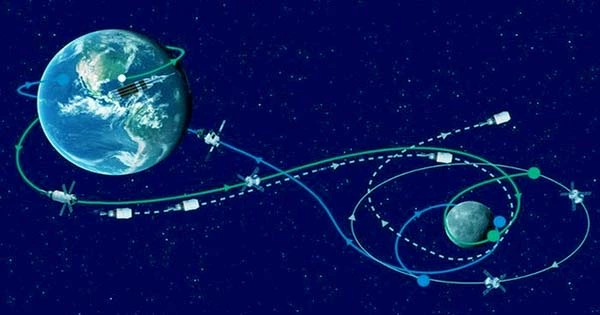

Jeremy Hansen is a mission specialist aboard Artemis 2, a spacecraft that will send four people around the moon in 2024. Hansen, a Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut, will fly into space for the first time on a significant mission: Artemis 2 will be the first astronaut mission to visit the moon in more than 50 years, and it will kick off human expeditions for NASA’s bigger Artemis program.

The Canadian Space Agency (CSA) chose Hansen in 2009, but he had to wait a time for a mission because Canada’s contributions to space are comparatively tiny, if mighty when compared to other agencies; for example, the CSA’s International Space Station (ISS) robotic contributions are 2.3%. However, he was sent to a number of senior positions on the ground. Examples include advising Canadian policymakers on space issues, mentoring and supervising the training schedules for the 2017 NASA astronaut class, and assisting in the development of a four-spacewalk marathon of procedures to repair ISS equipment that searches for evidence of dark matter.

With all of this experience behind him, Hansen says that ultimately donning a spacesuit for a mission is more of a continuation of what he’s been doing previously — a long journey of assisting other astronauts while recognizing Canada’s accomplishments in space.

“The only thing that feels different is this personal aspect of, ‘I’ve been working to actually fly in space and do the astronaut aspects,'” Hansen said in an exclusive 30-minute interview with Space.com on Friday (Oct. 27.) “It does feel closer, and much closer, than it has ever felt before.” So there’s that sensation, and it’s a lot of joy for me.”

Hansen will travel around the moon with three NASA astronauts (commander Reid Wiseman, pilot Victor Glover, and mission specialist Christina Koch) as part of an international collaboration and diversity mission. Thanks to CSA’s contribution to Canadarm3, which is being manufactured by the Canadian company MDA, Hansen will be the first non-American to exit Earth orbit. If all goes well, the robotic arm will service NASA’s proposed Gateway space station sometime in the next decade.

Hansen underlined that Artemis 2 is “very much a testing mission” in which the astronauts are all bringing their abilities to figure out the optimal path to the moon. The astronauts all know each other well and have gelled as a team, according to Hansen. When possible, even at airports or between training locations, the crew’s interactions focus on elements like as risk management and teamwork while working through those hazards.

The NASA astronauts have all already traveled on the ISS and each has unique abilities to contribute. Koch, who will be the first woman to walk on the moon, is a trained Antarctic scientist who spent nearly a year on the International Space Station. Glover, a former US Senate fellow and US Navy Captain, was the first Black astronaut on a long-duration ISS mission – and will be the first to depart Earth orbit as well. Wiseman, who previously flew carrier operations for the US Navy, will lead the quartet.

“We’re just creating the training, trying to figure out what we need with the team,” Hansen told reporters. “That’s a lot of fun. That’s a one-of-a-kind experience that I’m unlikely to have again.”

One example of the developing training processes is a simulator of Artemis 2’s Orion capsule. When images of the Artemis 2 crew testing out the hardware at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston surfaced recently, Hansen speculated that the impression may have been that everything was finished. While the sim is useful, more capabilities will be added; Hansen, like his Artemis 2 crewmates, is a military pilot with thousands of hours of experience to contribute.

“Our simulator is very, very limited, but we can get in it and go through some early procedures to the cruise phase of flight,” Hansen went on to say. “We’re able to work through turning off systems, resetting systems, and seeing failures in certain systems … we go in there two (astronauts) at a time and just work through these different simulation profiles.”

In September, the full Artemis 2 crew dressed up for a launch day, complete with a visit to the launch tower and a stroll across the gantry to where NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket will be waiting to send the astronauts off Earth one day. (The SLS and Orion are from Artemis 2 and were still under construction and unavailable at the time.)

Hansen stated that the opportunity gave great preparation for the crew and all ground staff in moving simulations from the tabletop to the launch location. They are learning how much time they need to allot for checklist items, what spare items may be required on-site, who transports what to the rocket, and other such questions.

During the launch simulation, Hansen and the team were focused on training, but he also took a minute to consider what it would be like when Artemis 2’s SLS is fuelled and ready for the lunar crew. “I suspect there will be moaning and groaning.” It’s going to be a lot of venting. “I don’t think it’ll be sitting there quietly; I imagine it’ll be talking to us,” he predicted.

“The other thought I had was, This is a really beautiful place to leave the planet,” Hansen continued, referring to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on Florida’s Space Coast. “You’re literally on the beach. As you ascend inside this massive rocket, you can see the ocean lapping against the coast. It’ll take you all the way to the moon. It’s just a really odd image to contemplate.”

Along with Koch, geology training has taken up some of Hansen’s time in recent months. In September, the Artemis 2 astronauts traveled to Kamestastin (also known as Mistastin) in northern Labrador with two astronauts from the 2017 class: NASA’s Raja Chari (who flew with ISS Expedition 66/67) and CSA’s Jenni Sidey-Gibbons (not yet assigned to a mission). According to CSA documentation, the crater is one of 31 known to have been produced by meteorites in Canada.

The site is rich in anorthosite, a rock found near the moon’s south pole, where future Artemis missions may land as early as 2025 or 2026. The distant excursion was designed to sharpen the astronauts’ geology skills, and was led by crater expert and planetary geologist Gordon Osinski of Western University in Ontario. The tour also provided an opportunity for the team to practice “expeditionary training,” or teamwork in distant situations. Hansen described Sidey-Gibbons as “one of the most skilled expeditionary skills teachers we have” in the Astronaut Office at JSC.

The lessons learned in Labrador will be valuable for the astronaut group, according to Hansen, especially since the corps already devotes one day each month to “core culture,” or building people skills. He described the meetings as “open conversations” concerning topics such as training debriefings, how people are feeling, and what they are learning.

Collaboration with locals in the field was also important to the geology trip, according to Hansen; the Mushuau Innu First Nation in what is now Labrador considers the crater to be sacred. Given that scientists value the crater’s surroundings for its anorthosite and rich geology, the intersection between “spirituality and science,” in Hansen’s words, was “unique, special, and powerful.”

“There’s this energy; they are very much on the path to humanity returning to the moon and understanding the moon in a new way,” he said of the Mushuau Innu elders, guardians, and community members he met. “It was neat that that resonated with them, that they will be part of this trip to the moon.”

The training has also been varied. The crew is learning how to utilize the Orion spacecraft’s five cameras to photograph the moon and Earth, as well as record their activities for “downlinks” to Mission Control. The astronauts recently spent time in a hospital cadaver lab and emergency room learning how to take care of wounds, stitch, do ultrasounds and catheters, and other routine medical procedures that may be required on their mission.

While the majority of Hansen’s time is now spent training, he and the other astronauts go on tours to promote awareness about Artemis 2 with various audiences and to gain insights from firms that may have expertise. Hansen and Wiseman, for example, spent time in the pits with the McLaren F1 team this month during the United States Grand Prix in Austin, Texas.

During a race, Hansen added, McLaren’s crew has the equivalent of a mission “capcom” (“capsule communicator”) communicating to the driver, as well as another member who feeds information to the capcom based on feedback from racing engineers. Sometimes, like in spaceflight, the team must make a decision in two or three seconds, and those judgments are debriefed in a “lessons learned” exercise. Hansen also stated that the Artemis teams expect that the McLaren crew would be able to visit Mission Control in Houston “to see what else they could glean” from spaceflight operations.

Hansen spoke with Space.com while in Toronto advertising the mission through broadcast and media appearances, as well as visits to two Canadian companies. Canadensys, for example, is providing hardware for Canada’s first lunar rover mission in 2026 or thereabouts. (Osinski will be in charge of the science on that initiative.) The second company, Kepler Communications, is developing a “Wi-Fi in space” system that will serve as a communications relay in space for satellites to send data back to Earth.

Hansen stated that he is learning a lot from the technical professionals at these companies. He went on to say that he was surprised to see that Canadensys generates nearly 80% of its business from exports, demonstrating the importance of Canadian space technology to the global economy. He stated that he tries to underscore Canada’s involvement in working under US leadership for Artemis whenever feasible. In conversations like this one, he discusses Canada’s well-known robotics specialization as well as new sectors such as artificial intelligence, food, and medical systems.

Hansen also recalled a trip on his Toronto tour during which he spoke to elementary school pupils. Given the rise of climate change and other concerns, one young woman spoke in front of a 600-person crowd about whether young people can expect a positive future on Earth. With someone that young concerned about the environment, Hansen said he felt “alarm bells” in his head.

“We need to remind them [students] that they can create a better future, but they must work for it.” You’ll have to focus and prioritize working together, bringing the globe together rather than merely dividing the world into portions. We’ll have to work together — and we’ll have to work hard to agree on things.”

When asked how his support group is doing — he is married with three teenagers and has a network of relatives and friends from all around the world helping him, in addition to a large group at CSA — Hansen said the community is “very inspired by this idea of going to the moon.” They are finding significance in the roles they have performed for many years while Hansen has been an astronaut, he said.

“Everyone on the team understands that doing this requires a large group of people. Nobody can do anything by themselves. So they feel that their labor is valuable not only in terms of completing the assignment but also in the altruistic sense that I’m always emphasizing: they’re doing a big service to humanity,” Hansen said.

“They’re leading by example, collaborating for the greater good of humanity.” Collaboration to solve challenges that matter for our future, not collaboration to tear each other down. “I think everyone feels like they’re on the winning team right now.”