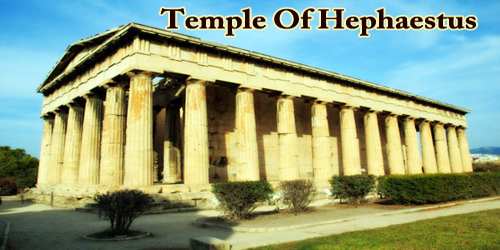

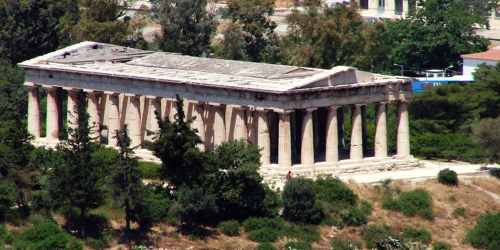

The Temple of Hephaestus or Hephaisteion (also “Hephesteum”; Ancient Greek: Ἡφαιστεῖον, Greek: Ναός Ηφαίστου) or earlier as the Theseion (also “Theseum”; Ancient Greek: Θησεῖον, Greek: Θησείο), is the best-preserved ancient temple in Greece. It was dedicated to Hephaestus, the ancient god of fire and Athena, goddess of pottery and crafts. It is a Doric peripteral temple and is located at the north-west side of the Agora of Athens, on top of the Agoraios Kolonos hill. From the 7th century until 1834, it served as the Greek Orthodox church of Saint George Akamates. The building’s condition has been maintained due to its history of varied use.

According to the archeologists, the temple was built around 450 B.C. at the western edge of the city, on top of Agoreos Koronos hill, and it is a classic example of Dorian architecture. The temple was designed by Iktinus, one of the talented architects who also worked on Parthenon, However, many other craftsmen worked at this fantastic temple.

Greek god Hephaestus was the son of Zeus and Hera, and a god of blacksmiths, metallurgy, and craftsmen. He was also the blacksmith of the gods, which was a pretty big job.

However, he may not have been the only deity worshipped here. Archeologists also suspect that this was a temple to Athena Ergani, the patron saint of Athens in the specific role as protector of potters and cottage industries. So, overall this seems to have been a temple dedicated to artisans and craftspeople of all kinds. For a long time, people around Athens believed this to be a temple of Theseus, the mythological hero, but a preponderance of metallurgy workshops and other crafts nearby support the theory that this was a place to worship Hephaestus and Athena Ergani.

Archaeological evidence suggests that there was no earlier building on the site except for a small sanctuary that was burned during the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC. The name Theseion or Temple of Theseus was attributed to the monument under the assumption it housed the remains of the Athenian hero Theseus, brought back to the city from the island of Skyros by Kimon in 475 BC, but refuted after inscriptions from within the temple associated it firmly with Hephaestus.

The temple disposed of a pronaos (anteroom) and an opisthodomos (back section), both distyle (two-columned) in antis. On the exterior, it was surrounded by a Doric colonnade having six columns on the narrow sides and thirteen columns on the longer sides. The entire building, from the crepis (stone base) to the roof, was made of marble produced in the quarries of Pendeli mountain (in Attica), while the architectural sculptures that adorned the temple were of marble produced in the quarries on the island of Paros. On the interior of the cella was a two-part colonnade forming the letter Π and at the far end was a pedestal, that supported the bronze ceremonial statues of Hephaestus and Athena, created by the sculptor Alkamenis; according to the traveler and geographer Pausanias, they were probably executed between 421 and 415 BC. The lavish sculptural decoration of the temple featured highly interesting metopes that adorned the east and the west side of the external colonnade. The east side numbered ten metopes that were visible from the Agora: they depicted nine of the feats of Hercules.

The pediment of the temple also seems to have been decorated with larger sculptures (which was a common practice in the Greek world). In this case, archeologists believe that the sculptures depict the hero Theseus and the people known as the Lapiths battling against the centaurs. We call this scene the Centauromachy. This is a major moment in Greek mythology, and a very popular subject found in many Greek temples, so its inclusion here is not surprising. However, it could explain why people thought this temple was dedicated to Theseus.

Construction started in 449 BC, and some scholars believe the building not to have been completed for some three decades, funds and workers having been redirected towards the Parthenon. The western frieze was completed between 445–440 BC, while the eastern frieze, the western pediment, and several changes in the building’s interior are dated by these scholars to 435–430 BC, largely on stylistic grounds. It was only during the Peace of Nicias (421–415 BC) that the roof was completed and the cult images were installed. The temple was officially inaugurated in 416–415 BC.

Notable sculptural representations also adorned the pediments of the temple. The west pediment depicted the fight of the Centaurs and the east pediment the reception of Hercules on mount Olympus or the birth of goddess Athena. Several among these sculptures inspired statues that were found in the surroundings of the temple, such as the fragmented and partially preserved complex of two feminine figures, one of which transports the other on her shoulders as if trying to save her life or the trunk of a dressed feminine figure where the movement is intensely underlined; the latter could be one of the acroteria (ornamental corner pieces) of the temple.

From the 7th century A.D. till 1834, this temple was an Orthodox church dedicated to Saint George Akamatus. The last Holy Mass took place in February 1833, when King Otto arrived in Greece. In the 19th century, the temple was used as a burial place for the non-Orthodox Europeans and philhellenes. Actually, the archeological excavations revealed many graves.

In 1834, King Otto ordered the building to be used as a museum where it actually remained as such until 1934. Today, this temple is one of the greatest ancient monuments in Greece. Reconstruction and excavation works are still carried out.

Information Sources: