There has been much dispute on the history of teeth. Researchers wondered whether teeth grow out from within since certain fishy relatives had dermal denticles, which are structures on the skin that resemble teeth. Some even had “teeth” on their eyeballs. Or did they move into the mouth from the body? New studies aim to provide a solution.

The authors of a Penn State study that was presented in the Journal of Anatomy stated that “the origin of oral dentition has been an intriguing subject.”

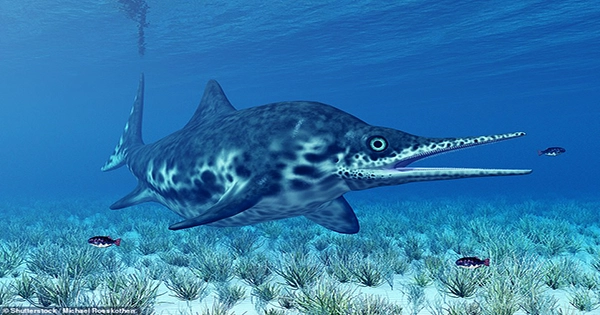

Following examinations into ancient sawfishes, Ischyrhiza Mira, discovered in rock formations in New Jersey, the controversy between “outside-in” and “inside-out” ideas for the origin of teeth has supposedly been resolved. And, according to the research, “outside-in” may have it.

For the majority of surviving toothed animals, eating and fighting are the two main purposes of their teeth. The lengthy rostrums of sawfishes are laced with unusual denticles that seem like they could serve as teeth in at least one of their primary purposes, which makes them extremely fascinating.

Researchers opted to look at the histological makeup of the teeth to gain a better understanding of the function of these sharp structures, as well as those that rest on their skin and in their mouths. They were able to determine that the pointed structures in the mouth were “considerably more complicated” than denticles elsewhere on the body using acid-etching methods and scanning electron microscopy.

How come? It’s true that eating may be a stressful experience, especially if you’re chowing down on live prey. Therefore, it seems sensible that there will be greater environmental demand for buildings to adapt to the more stresses they are subjected to.

The increased microstructural complexity found in the dentition of [sawsharks] is probably an adaptive reaction to resist mechanical stress brought on by feeding, according to the authors.

It is probable to explain why these structures are more complicated since the rostral and dental denticles are subjected to stronger stresses than those located more broadly across the skin, especially those at the peak of an animal’s noggin. At least in Ischyrhiza mira, the mechanical stresses connected to chewing, ripping, tearing, and self-defense possibly explain why these behaviors are more sophisticated.

So it makes sense that the simpler structures would exist closer to the place of origin where there was less mechanical stress. These structures’ internal architecture changed in response to their relocation within the mouth and increased responsibility.