Novel research shows that a reduced neural response to receiving rewards in teens predicts the first onset of depression, but not anxiety or suicidality. This is independent of pre-existing depressive or anxiety symptoms, as well as age or sex, which are already strong risk factors for depression. The study in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, published by Elsevier, is a step toward using brain science to understand and assess mental health risks.

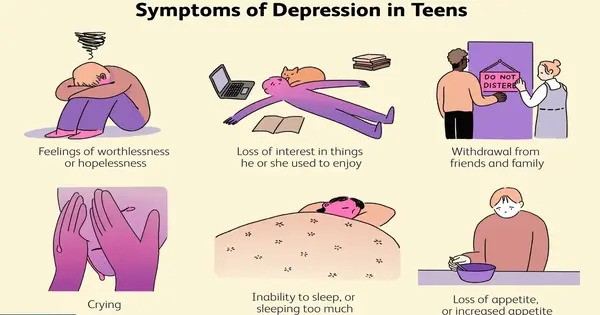

Mood and anxiety disorders among youth are a growing concern and have long-lasting consequences. Very few studies have identified premorbid neural markers that indicate the risk of the onset of these disorders in a teen’s life. This is particularly important given that 50% of children who experience one episode of depression or anxiety will go on to experience a second. Among those who have had two episodes, 80% will go on to have a third or more.

Investigators at the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, followed a group of 145 teens (64.8% female) with a family history of depressive or anxiety disorders, which put them at very high risk for developing these disorders themselves. Participating families were part of the Calgary Biopsychosocial Risk for Adolescent Internalizing Disorders (CBRAID) study, a longitudinal research program examining premorbid risk factors for first-lifetime onsets of mood and anxiety disorders in adolescence.

Researchers conducted nine- and 18-month follow-ups to assess whether participants had developed a major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or suicidal ideation. They found that a blunted response to reward feedback (also known as reward positivity) while playing a game during an EEG scan in which teens were told they either won or lost predicted the first onset of depression, but not anxiety or suicidality. This may suggest that teens who feel less pleasure or satisfaction when receiving rewards are particularly vulnerable to developing depression for the first time in their life.

Depression, anxiety, and suicidality are strongly linked, and are highly disabling and common problems that typically begin during adolescence. Reward processing is closely linked to depression and anxiety. However, little is known about if a blunted response to rewards precedes these conditions and confers risk for depression, anxiety, or suicidality.

Gia-Huy L. Hoang

First author Gia-Huy L. Hoang, second-year master’s student in neuroscience, University of Calgary, adds, “Evidence shows that kids with depressive or anxiety disorders, which often occur at the same time, generally exhibit a blunted response to rewards. Our research suggests that the brain’s response to rewards may be a marker that specifically indicates a risk for depression, rather than for anxiety or suicidality, in teens. Using EEG to measure how the brain responds to rewards is a simple and low-cost method to measure this response.”

Editor-in-Chief of Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging Cameron S. Carter, MD, University of California Irvine, comments, “Depression, anxiety, and suicidality are strongly linked, and are highly disabling and common problems that typically begin during adolescence. Reward processing is closely linked to depression and anxiety. However, little is known about if a blunted response to rewards precedes these conditions and confers risk for depression, anxiety, or suicidality. Research into specific biomarkers that can identify the risk of first-lifetime onsets of these conditions is highly important to understand and assess mental health risks.”

Senior investigator Daniel C. Kopala-Sibley, PhD, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Alberta Children Hospital Research Institute, The Mathison Centre for Mental Health Research & Education, and Department of Psychiatry, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, concludes, “Our findings are important as we work towards understanding the brain bases of why teens become depressed for the first time in their lives, which may ultimately further our ability to identify those at risk and intervene with them to prevent the onset of these disorders.”