Humans are presented with two options as soon as they consider life on other worlds. One would require 2,000 generations to live out their existence in the tight quarters of a spacecraft while adhering to a stringent population control policy, taking tens of thousands of years (with present technology). Mars is the alternative option.

The proximity of Mars, which prevents the need to force people out of airlocks when the spacecraft is at capacity, is among its many benefits. Additionally, an advance team would be able to establish the necessary infrastructure, and for maximum effectiveness, the squad should only consist of women.

In a study conducted by the Space Medicine Team at the European Space Agency in Germany and published in the journal Scientific Reports, it was discovered that compared to male astronauts, female astronauts require less water for hydration, total energy expenditure, oxygen (O2) consumption, carbon dioxide (CO2) production, and metabolic heat production.

In the study, “Effects of body size and countermeasure exercise on estimates of life support resources during all-female crewed exploration missions,” the team utilized an approach developed to estimate the effects of body “size” on life support requirements in male astronauts. Estimates for female astronauts were lower than for equivalent male astronauts for all metrics at all statures.

The study concludes that the female form is the most effective body type for space travel when taking into account the constrained space, energy, weight, and life support equipment crammed into a spacecraft on a lengthy voyage.

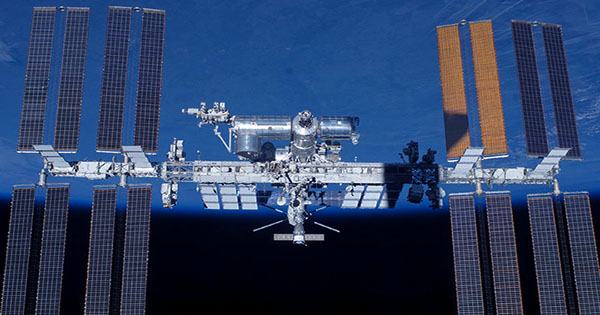

According to NASA, the cost of getting payloads to the International Space Station (ISS) is $93,400 per kg. The study found that on a 1080-day mission, a four-member all-female crew would require 1695 kg less food weight.

With some simple arithmetic, the mission could save over $158 million and free up 2.3 m3 of space (food packaging), the equivalent of approximately 4% of the habitable volume (60 m3) of a “Gateway” HALO module in NASA’s proposed lunar orbit space station. Both factors would be highly significant operationally, but there is more.

The influence of body size on total energy consumption in females was significantly smaller than in theoretical male astronauts in a prior study, with relative differences ranging from 5% to 29% lower.

Compared at the 50th percentile stature for US females (1.6m), the reductions were even more significant at 11% to 41%. This translates into reduced use of oxygen, production of CO2, metabolic heat, and water use.

The bodies of astronauts experience negative effects after being subjected to prolonged microgravity in space. Muscle atrophy, bone loss, and decreased aerobic and sensorimotor capability are all caused by physiological changes, which may have an impact on crewmember health and ability to do mission-related duties.

The term “countermeasure exercise” refers to physical activity performed in space that is intended to offset the physiological effects of being weightless. Astronauts need more water to rehydrate after these exercises (two 30-minute aerobic workouts, six days a week). They also produce more CO2 and heat during these workouts.

Smaller stature generally equates to less energy required, but missions requiring countermeasure training exacerbate this gap because larger bodies require more energy, use more oxygen, produce more CO2, and generate more heat.

The study also discovered that women lost 29% less water through sweating following a single session of aerobic countermeasure exercise, resulting in a need for 29% less water to rehydrate.

Theoretically, female astronauts have lower oxygen requirements while at rest and during exercise than male astronauts because they are smaller and have lower relative VO2max values (the rate at which the heart, lungs, and muscles can effectively use oxygen during exercise).

Functional workplaces have benefits beyond resource efficiency, particularly when several astronauts are working in a small space, as is frequently the case on the International Space Station (ISS). The astronauts on board the ISS have just enough room to stand and, if necessary, work back-to-back or shoulder to shoulder.

The proposed NASA Gateway vessel has smaller spaces, which makes it less comfortable for numerous crew members to work together. A smaller group might work just as effectively in smaller settings.

According to the study data and the shift toward smaller diameter habitat space for currently proposed mission modules, all-female crews may have several operational benefits during upcoming human space exploration missions, with shorter females showing the greatest operational improvement.