The funding for a satellite telescope to see if the Alpha Centauri system — the closest planetary system to Earth – includes Earth-like planets in its habitable zones has been authorized.

Although it may be suited for investigating a few additional stars, the project’s significance is nearly entirely dependent on what we will discover about these two stars. Fortunately, it costs a thousandth of the price of other space telescopes.

Only a few stars are close enough that sending probes to them within a human lifetime is even conceivable. Professor Pete Klupar of Breakthrough Watch stated in a statement, “These close planets are where mankind will take our first steps into interstellar space with high-speed, futuristic, robotic probes.” “We predict a handful of rocky planets like Earth circling at the correct distance for liquid surface water to be viable if we consider the closest few dozen stars.”

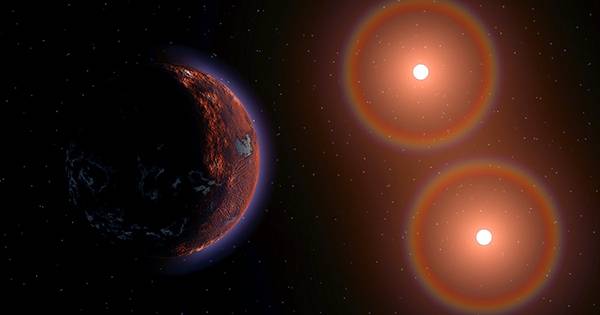

Planets have been discovered orbiting the nearest red dwarfs Proxima Centauri and Barnard’s star, but we have had less luck with planets closer to the Sun (with one exception). Alpha Centauri A and B are very intriguing since they are both quite close to and brightly similar to the Sun, yet we don’t even know if they have worlds to investigate.

Existing planet-finding methods are shockingly unsuitable for locating planets in the habitable zone of these variable sunlike stars, therefore Professor Peter Tuthill of the University of Sydney has devised a new way.

Because launching devices into space, particularly delicate instruments like telescopes, is so expensive, the standard strategy has been to pursue multi-functionality. Tuthill, on the other hand, is creating “a scalpel rather than a Swiss Army knife.” He plans to start in 2023 with financing from the Breakthrough Institute and the Australian Government.

The TOLIMAN telescope will be most suited for searching for planets in neighboring bright binary star systems, especially those in which the stars are of similar brightness. Therefore, it is fortunate that 4.3 light-years distant, we have a pair of stars that are practically ideally suited to TOLIMAN’s capabilities.

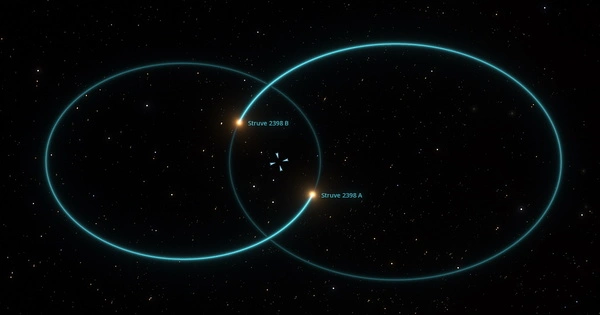

The name TOLIMAN derived from the Arabic term for Alpha Centauri. It creates a complicated pattern using a diffractive pupil lense that permits highly exact measurements of a star’s position (astrometry). It will detect minute shifts in star positions caused by the drag of any orbiting planets.

It’s comparable to the radial velocity approach, which led to the discovery of many of the early planets beyond our solar system, but it’s much more sensitive at small distances (astronomically speaking), allowing for the detection of lighter planets further away from their stars.

Unfortunately, astrometry not only loses capacity faster than radial velocity with distance, but it also requires a frame of reference, according to Tuthill. The Gaia satellite telescope utilizes distant background stars as a reference, but Tuthill told IFLScience “you need at least a meter [3-foot] broad telescope for that.” It costs billions of dollars to launch something that large and sensitive into orbit. TOLIMAN, on the other hand, goes considerably smaller, utilizing the two stars of Alpha Centuari as references. At habitable distances from either star, planets of even near to Earth mass will cause it to wobble in comparison to its partner.

The difficulty, according to Tuthill, is that we will not be able to determine which star is wobbling and which is stable, i.e., which one has the planet. Despite this, the stars are close enough in mass and brightness that their habitable zones have the same orbital period. The finding of a planet orbiting either star will encourage more research and exploration missions both from Earth and on the other side of the galaxy.