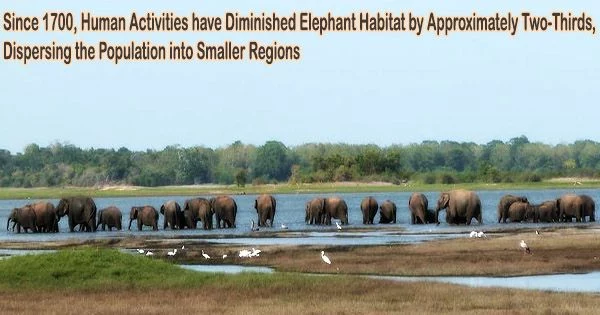

Asian elephants are one of the most endangered big species, despite their iconic position and long affiliation with humans. They are thought to number between 45,000 and 50,000 individuals globally and are threatened throughout Asia as a result of human activities such as deforestation, mining, dam construction, and road construction, which have harmed several ecosystems.

We investigated the centuries-long history of Asian landscapes that were historically excellent elephant habitat and were frequently managed by local groups prior to the colonial era in a recently published study. Understanding this history and re-establishing some of these relationships, in our opinion, may be the key to living with elephants and other huge wild creatures in the future.

How have humans affected wildlife?

It is difficult to quantify human impacts on wildlife in a region as huge and diverse as Asia over a century ago. Many species have little historical data. Museums, for example, only house specimens acquired from certain locations.

Many creatures have highly precise ecological requirements, and there is frequently insufficient data on these qualities at a fine scale going back a long time. For example, a species may favor specific microclimates or flora types that are only found at certain elevations.

For nearly two decades I’ve been studying Asian elephants. As a species, these animals are breathtakingly adaptable: They can live in seasonally dry forests, grasslands or the densest of rain forests.

We knew we could understand how land-use changes had affected elephants and other species in these areas if we could connect elephant habitat requirements to data sets demonstrating how these habitats changed over time.

Defining elephant ecosystems

Asian elephants’ home ranges can range from a few hundred to a few thousand square miles. However, because we couldn’t know where elephants would have been centuries ago, we had to simulate the possibilities based on where they are now.

We can discern regions where wild elephants may have lived in the past by recognizing the environmental features that match to where they dwell now. In principle, this should represent “good” habitat.

Many scientists today use this type of model to determine certain species’ climatic requirements and estimate how areas favorable for those species may alter in the face of future climate change scenarios. We applied the same logic retrospectively, using land-use and land-cover types instead of climate change projections.

We drew this information from the Land-Use Harmonization (LUH2) data set, released by a research group at the University of Maryland. The group mapped historical land-use categories by kind, beginning in 850, far before the emergence of nations as we know them today, with fewer significant population centers, and lasting up to 2015.

My co-authors and I (Shermin de Silva) first compiled records of where Asian elephants have been observed in the recent past. We limited our study to the 13 countries that today still contain wild elephants: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam.

We eliminated places where elephant populations are prone to clashes with humans, such as heavily farmed landscapes and plantations, to avoid categorizing these zones as “good” elephant habitat. We included places with less human impact, such as selectively cut woods, because they contain a lot of food for elephants.

Then, at our remaining locations, we utilized a machine-learning algorithm to assess what forms of land use and land cover existed. This allowed us to map out where elephants would live in the year 2000. We were able to construct maps of places that included acceptable habitat for elephants and show how those areas had evolved over time by applying our model to earlier and later years.

Dramatic declines

Land-use patterns on every continent changed dramatically beginning with the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s and continuing through the colonial era into the mid-20th century. Asia was no exception.

For most areas, we found that suitable elephant habitat took a steep dive around this time. We estimated that from 1700 through 2015 the total amount of suitable habitat decreased by 64%.

More than 1.2 million square miles (3 million square kilometers) of land were converted for plantations, industry and urban development. The majority of the shift in prospective elephant habitat happened in India and China, each of which underwent conversion in more than 80% of these landscapes.

In other parts of Southeast Asia, such as a vast hotspot of elephant habitat in central Thailand that was never colonized, habitat degradation occurred much later, in the mid-20th century. This coincides with logging during the so-called Green Revolution, which brought industrial agriculture to many regions of the world.

Could the past be the key to the future?

Looking back over centuries of land-use change reveals exactly how profoundly human actions have destroyed habitat for Asian elephants. We found that the losses we evaluated far exceeded projections of “catastrophic” human impacts on so-called wilderness or forests in recent decades.

Our data demonstrates that if you were an elephant in the 1700s, you could easily range across 40% of the habitat in Asia because it was one vast, connected area with multiple ecosystems where you might reside. This enabled gene flow among many elephant populations. But by 2015, human activities had so drastically fragmented the total suitable area for elephants that the largest patch of good habitat represented less than 7% of it.

Sri Lanka and peninsular Malaysia have a disproportionately high share of Asia’s wild elephant population, relative to available elephant habitat area. Thailand and Myanmar have smaller populations relative to area. Surprisingly, both of these countries have considerable captive or semi-captive elephant populations.

Today, less than half of the places with wild elephants have suitable habitat for them. Elephants’ use of increasingly human-dominated settings as a result leads to encounters that are damaging to both elephants and humans.

This long view of history, however, reminds us that protected areas alone cannot support elephant numbers because they are simply too small. Indeed, for millennia, human societies have molded these very landscapes.

Today, balancing human subsistence and livelihood demands with wildlife needs is a critical concern. Restoring traditional ways of land management and local care of these landscapes can be critical in the future protection and recovery of ecosystems that serve both people and wildlife.