Longline fishing poses the biggest threat to sharks that live in the open ocean, with fishers reportedly catching 20 million pelagic sharks each year while searching for tuna and other sought-after species.

Now, a new study published in Current Biology on November 21, 2022, shows that a new technology, known as “SharkGuard,” could allow longline fishing to continue while reversing the dramatic decline in endangered sharks worldwide.

“The main implication is that commercial longline fishing may continue, but it won’t always necessarily result in the mass bycatch of sharks and rays,” said Robert Enever of Fishtek Marine, Dartington, Devon, United Kingdom. “This is important in balancing the needs of the fishers with the needs of the environment and contributes to national and international biodiversity commitments for long-term sustainability.”

Based on data showing that more than 100 million sharks, skates, and rays are caught annually by commercial fisheries around the world, Enever and his colleagues recognized the urgent need to slow or even reverse the loss in global shark populations.

A quarter of sharks and rays also are now classified as threatened. They reasoned that shark deterrents that were showing promise in protecting divers and surfers from sharks would also find application in the tuna fishery to protect sharks from bycatch.

Against the relentless backdrop of stories of dramatic declines occurring across all species, it is important to remember that there are people working hard to find solutions. SharkGuard is an example of where, given the appropriate backing, it would be possible to roll the solution out on a sufficient scale to reverse the current decline in global shark populations.

Robert Enever

How does it work?

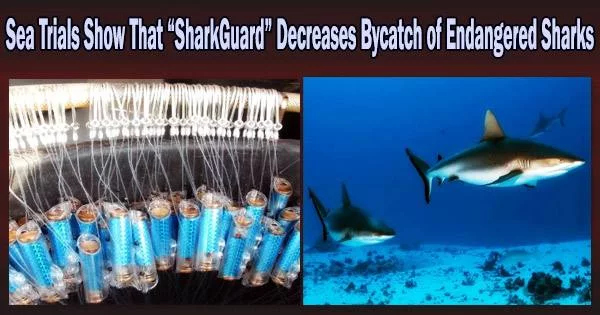

SharkGuard emits a small, localized, pulsing electric field. It produces an electric field around a baited hook when attached to the fishing line. The idea is to prevent sharks and rays from biting while still allowing other fish to be hooked. These animals can detect the electric signals via electroreceptors.

To find out how well it worked, the researchers ran sea trials in July and August 2021 in southern France. Two fishing vessels fished 22 longlines on 11 separate trips, deploying a total of more than 18,000 hooks. Their research revealed that compared to conventional control hooks, SharkGuard hooks considerably decreased the quantity of pelagic stingrays and blue sharks collected.

For sharks and rays, respectively, the catch rate of these species per unit effort decreased by 91% and 71%. SharkGuard on the hook did not have a substantial impact on the catch rates of bluefin tuna.

“The sharks do not take the bait and do not get (by)caught on the hooks,” Enever said.

The researchers point out that SharkGuard provides a more complete solution than catching and releasing bycaught animals, including sharks. Sharks and fishing equipment would interact far less if its use were expanded to encompass entire fisheries.

The gadget does, however, currently have some restrictions, such as the requirement for frequent battery replacements. They’re now working to overcome this barrier, so fishers could “fit and forget” it, while still protecting sharks and other bycatch species.

It’s expected that a full set of induction-charged SharkGuard devices for 2,000 hooks would cost around $20,000 and would last 3 to 5 years (~$4-7K per annum), which they note is a modest annual cost for most commercial tuna fishing operations.

They now advise retailers who want to improve the sustainability of their supply chain, as well as fishermen who suffer high shark and ray bycatch, to get in touch with Fishtek Marine as soon as sea testing and engineering advances are scheduled for commercialization.

“There is hope!” Enever said. “Against the relentless backdrop of stories of dramatic declines occurring across all species, it is important to remember that there are people working hard to find solutions. SharkGuard is an example of where, given the appropriate backing, it would be possible to roll the solution out on a sufficient scale to reverse the current decline in global shark populations.”