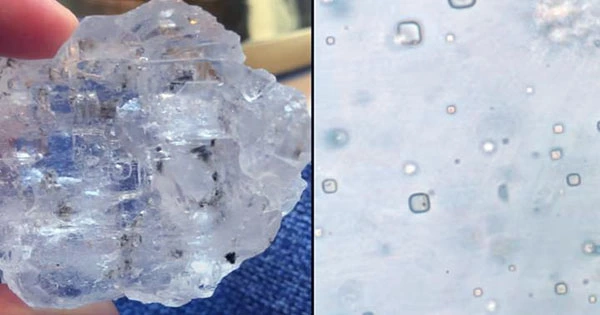

Scientists recently revealed the finding of ancient bacterial and algae cells inside an 830-million-year-old rock salt crystal, which might still be alive. The researchers have now revealed a little more about their new study, implying that they want to split open the crystal in the hopes of uncovering whether or not this ancient life is still alive. The scientists employed a variety of imaging techniques to identify well-preserved organic compounds contained within fluid inclusions buried in an 830-million-year-old fragment of rock salt, commonly known as halite, as first published in the journal Geology earlier this month. They claim that these things have a striking similarity to prokaryotes and algal cells.

Because crystalized rock salt cannot sustain ancient life on their own, the prospective microbes are not stuck within the crystals like an ant caught in amber. Small quantities of water and tiny life can be trapped in initial fluid inclusions as rock salt crystals develop from the evaporation of saline seawater. This remarkable gem may be seen in action in the video below. As the researcher carefully slides the crystal around, notice how a bubble appears within it — it’s within this little fluid-filled cavity that they discovered the potential signs of life.

Previous research has suggested that microscopic life may persist in a latent condition for hundreds of millions of years within the fluid inclusions of salt crystals, so the team is eager to find out if these small cells are still alive. In an interview with NPR, research author Kathy Benison, a geologist from West Virginia University, said they want to open up the crystal to see if the biological items are still alive or have died.

“There are little cubes of the original liquid that the salt was formed from. The fact that we found forms that are consistent with what we would anticipate from microbes was a pleasant surprise. And they could still be alive within that 830-million-year-old preserved microhabitat “NPR spoke with Benison. While reintroducing 830-million-year-old living forms into the current world may not appear to be the most disaster-proof strategy, she is convinced it will be carried out with extreme prudence.

“It sounds like a horrible B-movie,” Benison remarked, “but there’s been a lot of thorough work going on for years to try to find out how to accomplish it in the safest possible way.” Other scientists agreed with Benison that the accomplishment should not be a problem if done carefully and appropriately. After all, a creature that is hundreds of millions of years old is unlikely to be well-adapted to infecting or harming people. “An environmental creature that has never encountered a person will not be able to enter our bodies and cause sickness. So, from a scientific standpoint, I have no concerns about that “Bonnie Baxter, a biologist at Westminster College in Salt Lake City who was not engaged in the study, expressed her opinion.