Anastasios “Andy” Tzanidakis and James Davenport openly admit their fascination in strange stars. In search of “stars behaving strangely,” University of Washington astronomers came across Gaia17bpp when they received an automated signal from the Gaia survey. This star has steadily become brighter over a 2 1/2-year period, according to survey data.

As Tzanidakis will report on Jan. 10 at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle, follow-up analyses indicated that Gaia17bpp itself wasn’t changing. Instead, the star is probably a rare kind of binary system, and its apparent brightening marked the end of an uncommon stellar companion’s years-long shadow of the star.

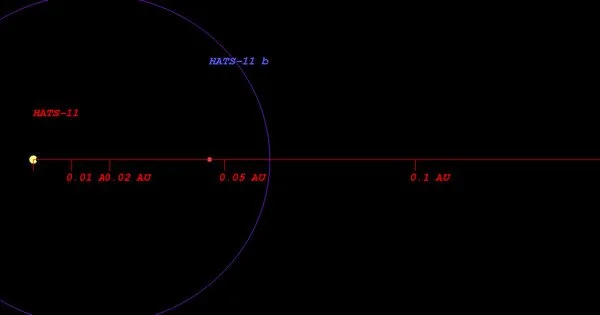

“We believe that this star is part of an exceptionally rare type of binary system, between a large, puffy older star Gaia17bpp and a small companion star that is surrounded by an expansive disk of dusty material,” said Tzanidakis, a UW doctoral student in astronomy. “Based on our analysis, these two stars orbit each other over an exceptionally long period of time as much as 1,000 years. So, catching this bright star being eclipsed by its dusty companion is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Tzanidakis and Davenport, a research assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Washington and associate director of the DiRAC Institute, had to undertake some detective work to get to this conclusion because the Gaia spacecraft’s observations of the star only dated back to 2014.

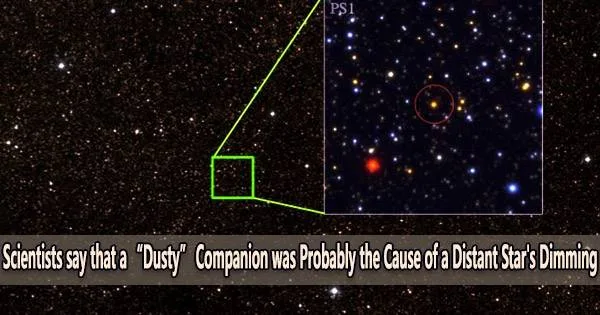

First, they stitched together Gaia’s observations of the star with observations by other missions stretching back to 2010 including Pan-STARRS1, WISE/NEOWISE and the Zwicky Transient Facility.

This was a serendipitous discovery. If we had been a few years off, we would’ve missed it. It also indicates that these types of binaries might be much more common. If so, we need to come up with theories about how this type of pairing even arose. It’s definitely an oddity, but it might be much more common than anyone has appreciated.

Anastasios “Andy” Tzanidakis

Along with the Gaia data, those observations demonstrated that Gaia17bpp dimmed by around 4.5 orders of magnitude, or 45,000 times. Between 2012 to 2019, or almost seven years, the star remained faint. That seven-year dull came to an end with the abrupt brightening that the Gaia scan had discovered.

No other stars near Gaia17bpp showed similar dimming behavior. Through the DASCH program, a digital catalog of more than a century’s worth of astro-photographic plates at Harvard, Tzanidakis and Davenport analyzed observations of the star stretching back to the 1950s.

“Over 66 years of observational history, we found no other signs of significant dimming in this star,” said Tzanidakis.

Gaia17bpp, according to the two, is a member of a unique variety of binary star system with a stellar companion that is only dusty.

“Based on the data currently available, this star appears to have a slow-moving companion that is surrounded by a large disk of material,” said Tzanidakis. “If that material were in the solar system, it would extend from the sun to Earth’s orbit, or farther.”

Over the years, a few more comparable, “dusty” systems have been discovered, most notably Epsilon Aurigae, a star in the constellation Auriga that is overshadowed by a very massive, faint companion for two out of every 27 years.

The system that Tzanidakis and Davenport found stands out among these few dusty binaries because it has by far the longest eclipse, lasting approximately seven years. Gaia17bpp and its partner are likewise so far apart from one another, unlike the Epsilon Aurigae binary, that it would be centuries or more before a keen observer on Earth experiences another similar eclipse.

The identity of the dusty companion in Epsilon Aurigae and other systems is up for debate. According to some preliminary evidence, Gaia17bpp’s companion may be a tiny, massive white dwarf star. The source of its debris disk is also a mystery.

“This was a serendipitous discovery,” said Tzanidakis. “If we had been a few years off, we would’ve missed it. It also indicates that these types of binaries might be much more common. If so, we need to come up with theories about how this type of pairing even arose. It’s definitely an oddity, but it might be much more common than anyone has appreciated.”

David Wang, a UW graduate student in astronomy, and Eric Bellm, a research assistant professor of astronomy at the UW, are additional team participants on this investigation.