For the first time, scientists modified plants’ microbiomes, increasing the abundance of ‘good’ bacteria that defend the plant against disease. The findings could significantly cut the use of environmentally harmful pesticides. A breakthrough might significantly reduce the use of pesticides while also opening up new options to improve plant health.

For the first time, scientists modified plants’ microbiomes, increasing the abundance of ‘good’ bacteria that defend the plant against disease. Researchers from the University of Southampton, China, and Austria reported their findings in Nature Communications, which might significantly cut the use of environmentally harmful pesticides.

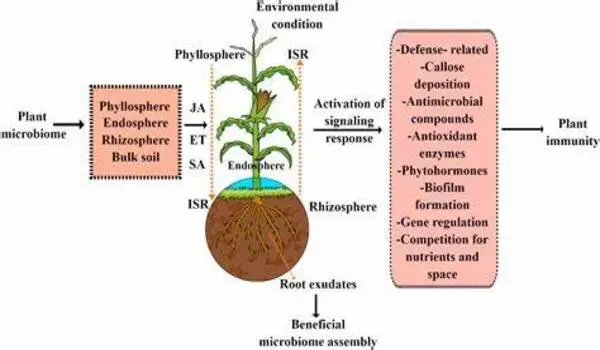

The importance of our microbiome, the diverse collection of microbes that dwell in and around our bodies, particularly in our stomachs, is becoming more widely recognized. Our gut microbiomes influence our metabolism, risk of illness, immune system, and even our mood.

For the first time, we’ve been able to change the makeup of a plant’s microbiome in a targeted way, boosting the numbers of beneficial bacteria that can protect the plant from other, harmful bacteria.

Dr Tomislav Cernava

Plants, too, have a wide range of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms that reside in their roots, stems, and leaves. For the past decade, scientists have conducted extensive research on plant microbiomes to better understand how they affect plant health and disease susceptibility.

“For the first time, we’ve been able to change the makeup of a plant’s microbiome in a targeted way, boosting the numbers of beneficial bacteria that can protect the plant from other, harmful bacteria,” says Dr Tomislav Cernava, co-author of the paper and Associate Professor in Plant-Microbe Interactions at the University of Southampton.

“This breakthrough could reduce reliance on pesticides, which are harmful to the environment. We’ve achieved this in rice crops, but the framework we’ve created could be applied to other plants and unlock other opportunities to improve their microbiome. For example, microbes that increase nutrient provision to crops could reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers.”

The international research team discovered that one specific gene found in the lignin biosynthesis cluster of the rice plant is involved in shaping its microbiome. Lignin is a complex polymer found in the cell walls of plants — the biomass of some plant species consists of more than 30 percent lignin.

First, the researchers observed that when this gene was deactivated, there was a decrease in the population of certain beneficial bacteria, confirming its importance in the makeup of the microbiome community.

The researchers then performed the converse, over-expressing the gene to increase production of a certain sort of metabolite — a tiny molecule produced by the host plant during its metabolic activities. This raised the proportion of beneficial bacteria in the plant’s microbiome.

When these altered plants were challenged to Xanthomonas oryzae, a disease that causes bacterial blight in rice crops, they proved significantly more resistant than wild-type rice.

Bacterial blight is frequent throughout Asia and can cause significant loss of rice production. It is typically handled with polluting pesticides, thus developing a crop with a protective microbiome could assist improve food security and the environment.

The research team are now exploring how they can influence the presence of other beneficial microbes to unlock various plant health benefits.