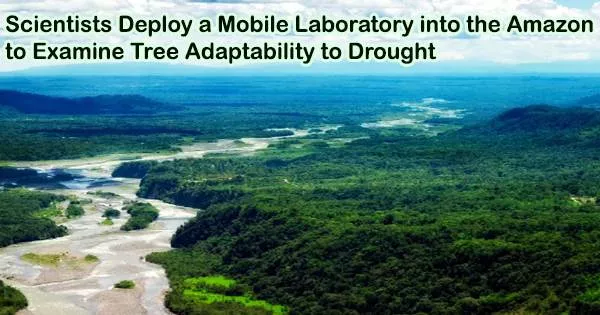

Dr. Julia Tavares, an ecologist, frequently has to examine how to collect data from remote sites. Nothing, however, had prepared her for the hurdles she would confront when she began her Ph.D. at the University of Leeds.

As a PhD researcher in the School of Geography, she organized and subsequently led a trip into the Amazon rainforest to collect data from the prominent trees that existed in Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia.

The project entailed supervising the collection of hundreds of tissue samples, which had to be done in the middle of the night, all in the name of cutting-edge science.

The researchers worked in high humidity and temperatures that reached 30°C by 8 a.m. and more than 35°C by lunchtime. And the hot, humid weather came clouds of mosquitoes.

The project, which involved 80 scientists and support employees, looked at how different tree species have adapted to drought and how sensitive different forest zones would be to future climate change.

It was the first study of the water stress experienced by trees throughout the Amazon basin and how they might cope if, as some climate models suggest, the Amazon warms dramatically and rainfall patterns alter.

The findings of the research have been published today, Wednesday, April 26 (2023), in the journal Nature.

Sampling from the tree canopy

Samples were taken from more than 540 trees. These were the major canopy species, with some reaching heights of more than 30 meters. The tissue samples were utilized to determine how hydrated the trees were over a 24-hour period.

I consider this study very important because it helps us to understand how forests will behave with the effect of climate change. Especially in the Amazon Cerrado transition areas, which are more susceptible to climate extremes than in the core areas.

Dr. Halina Soares Jancoski

The scientists needed to measure hydration during periods of low and high-water stress. To do this, sampling was conducted at three a.m., when the rainforest was completely dark and plants were replenishing their water levels, then again at lunchtime.

As part of the mission, the scientific team transported a mobile laboratory packed in 16 flight cases into the forest, along with massive nitrogen gas cylinders.

Dr. Tavares said, “We had a team of expert tree climbers whose job it was to use ropes and climbing gear to ascend the trees and get the samples.”

“We would survey the site the day before we intended to take the samples. Remember, we were working in a dense rainforest and some of the sampling was happening at night, so we needed to mark the trees and the branches that we wanted for the tissue samples.”

The tree climbers utilized telescopic scissors, which can reach out across the forest and pluck the branch they were looking for.

Dr. Carol Signori-Muller, an ecophysiologist formerly at University of Campinas, Brazil, and now with the University of Exeter, said the rainforest is a beautiful and fantastic place that took on a different character at night.

She said, “At night it is very dark. The moonlight can be blocked out by the dense overhead vegetation. And it is very silent.”

“There is hardly any sound from the birds. All you can hear are the croaking of frogs or the movement of branches. You become attuned to the sounds around you because you need to be aware that something can suddenly appear from behind a bush.”

A jaguar emerged from the foliage during one of the daylight sample sessions and began playing with the ropes tied to the climbing gear, much like a cat would with a ball of wool.

Dr. Tavares added, “The team had to stop what we were doing and keep away and just watch the jaguar, who did end up destroying some of the climbing gear.”

The scientists and support staff would camp or stay in field station housing while traveling to the several forest locations in four-by-four vehicles or by boat.

The team wore long boots to protect themselves from the snakes that live in the rainforest.

The study’s findings will aid in identifying rainforest zones most vulnerable to climate change, allowing conservationists to direct resources and policies toward particular places.

Dr. Halina Soares Jancoski, who took part in the expedition while at the State University of Mato Grosso in Brazil and is now with the Environment Secretariat of the Municipality of Nova Xavantina, in the central west region of Brazil, said, “I consider this study very important because it helps us to understand how forests will behave with the effect of climate change. Especially in the Amazon Cerrado transition areas, which are more susceptible to climate extremes than in the core areas.”

Dr. Tavares added, “At the start of my Ph.D., if you said to me that I would be involved in a major expedition into the Amazon and would have led a scientific collaboration into one of the most important ecological questions facing this hugely important ecosystem, I would have thought you were joking.”

“But, together with an amazing team, that is exactly what we have done.”