When a large hurricane churns up storm surges and heavy, soaking rains, according to University of Rhode Island professors Andrew Davies and Coleen Suckling, the storm sweeps garbage from the land into our rivers and beaches.

Plastics, the ubiquitous consumer material found in many products and packaging, are among the items being transported. The issue is that plastic takes an unusually long time to decompose in the natural environment. Plastic waste is found in ports, estuaries, and on land.

However, most of it is still circulating in the water and has the potential to settle on the bottom. Two linked carbon-based fuels, oil, and natural gas are at the foundation of global climate change and the global plastics pollution problem.

Not only are these two major contributors to climate change, but they also play an important role in the production of plastics. The migration of garbage from land to our oceans, and vice versa, will only worsen as storms increase and grow more common.

Davies, an associate professor of biological sciences, and Suckling, an assistant professor of sustainable aquaculture, are now part of an international team of researchers, including those from the Zoological Society of London and Bangor University in Wales, who are investigating the compounding effect of climate change and plastics, an issue that is often overlooked.

Plastic pollution has an influence all across the world, from the summit of Mount Everest to the lowest depths of the ocean. Both are threatening ocean biodiversity, with climate change raising ocean temperatures and bleaching coral reefs, and plastic destroying ecosystems and harming or killing marine life. It’s not a case of which issue is most important, it’s recognizing that the two crises are interconnected and require joint solutions.

Professor Heather Koldewey

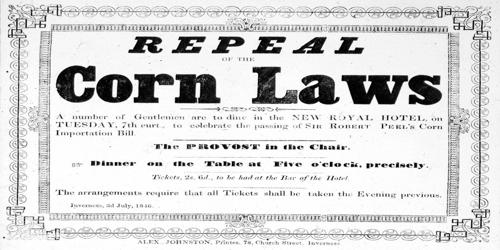

The researchers discovered three key links between the climate issue and plastic pollution, the first of which is how plastic contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions from manufacture to disposal. The second shows how extreme weather, such as hurricanes and floods, disseminate pollution and make it worse. The third factor to consider is the impact of climate change and plastic pollution on marine animals and ecosystems that are sensitive to both.

Helen Ford, a Ph.D. student at Bangor University who collaborated with Davies and Suckling at Bangor, lead the research. The team’s findings were published in the journal Science of the Total Environment in September. The study’s principal author was Professor Heather Koldewey, a senior technical specialist of the Zoological Society of London.

“Climate change is undoubtedly one of the most critical global threats of our time,” Koldewey said in a press announcement issued by the zoological society. “Plastic pollution has an influence all across the world, from the summit of Mount Everest to the lowest depths of the ocean. Both are threatening ocean biodiversity, with climate change raising ocean temperatures and bleaching coral reefs, and plastic destroying ecosystems and harming or killing marine life. It’s not a case of which issue is most important, it’s recognizing that the two crises are interconnected and require joint solutions.”

Davies said Ford organized the international team that conducted the study. “The premise of the paper addresses the fact that so many people view plastics pollution and climate change as separate things when they are not,” Davies said. “They arise from the same principle material, oil.”

“Climate change and plastic pollution have many similarities, including how we need to address them. We need international collaborations to address this problem, which essentially stems from the over-consumption of finite resources.”

Plastic pollution has an influence all across the world, from the summit of Mount Everest to the lowest depths of the ocean. Both are threatening ocean biodiversity, with climate change raising ocean temperatures and bleaching coral reefs, and plastic destroying ecosystems and harming or killing marine life.

“The whole area was flooded with floating white polystyrene particles. The storm had split apart the walkway floating platforms in this marina and spilled out the polystyrene contents, posing a pollution risk,” Suckling said. “This was at a site where an invasive species was being controlled, but plastics which spread from the site could increase the risk of transporting this invasive species.”

Scientists are investigating the capacity of plastics to carry invasive species hundreds of kilometers, according to Suckling.

“Since Hurricanes Henri and Ida, we have been looking at storm-induced transport of plastics,” Davies said. “We sent our students out to collect samples from Narragansett Bay before and after the storms so we could start seeing what the impact would be. We are working on that data now. We want to see what the impact of these storms is on plastics in our oceans.”

“The great thing about Narragansett Bay is it is so well studied. We are building on 60 years of research at URI or even longer,” Davies said.

Rhode Island is a perfect site to perform the job, according to Davies, because of the state’s competence in this area, which includes its institutions and administrative agencies.

“We have a wide range of disciplines, a relatively small number of stakeholders, and a wide range of habitats,” he said.

Suckling has published two publications on the effects of microplastics on marine life, notably sea urchins, since arriving at URI. One of them, which looks into how varied feeding patterns affect how sea urchins react to microplastics, was published in the online version of Science of the Total Environment in September 2020.

“It’s still a relatively new area of science, where we still have much to understand. My work has shown that when we look at sea urchin species with slightly different feeding habits, we observe species-specific responses to ingesting microplastics,” Suckling said.

According to Suckling, this shows the potential for eating behaviors to function as a possible indication for sensitivity to microplastic ingestion, which might be useful for impact assessments of plastic pollution and control measures.

Meanwhile, Davies is collaborating with Suckling on a Rhode Island Sea Grant study that looks at the linkages between climate change and plastics.

“What no one has really done until now is quick-start the conversation about plastics and climate change in a concerted way,” Suckling said. “We expect over the next several years, a lot more research will be done in the area.”

Suckling believes that if marine ecosystems or creatures are already stretched beyond their limits as a result of climate change, adding other challenges to the mix might drive them over the edge.