Even if global temperatures begin to fall after peaking this century due to climate change, the risks to biodiversity could last for decades, according to a new study from UCL and the University of Cape Town. The paper, published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, simulates the potential impacts on global biodiversity if temperatures rise by more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels before falling back.

The Paris Agreement, signed in 2015, aims to keep global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably 1.5 degrees Celsius. However, as global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, many scenarios now include a multiple decades-long’overshoot’ of the Paris Agreement limit, before accounting for the effects of potential carbon dioxide removal technology to reverse dangerous temperature rises by 2100.

Climate change and other human-caused factors are already causing an ongoing biodiversity crisis, with mass die-offs in forests and coral reefs, altered species distributions and reproductive events, and a slew of other negative consequences.

Co-author Dr Alex Pigot (UCL Centre for Biodiversity & Environment Research, UCL Biosciences) said: “We have investigated what will happen to global biodiversity if climate change is only brought under control after a temporary overshoot of the agreed target, to provide evidence that has long been missing from climate change research.

“We discovered that a large number of animal species will continue to live in dangerous conditions for decades after the global temperature reaches its peak. Even if we manage to halt global warming before species are irreversibly lost from ecosystems, the ecological disruption caused by unsafe temperatures may last another half century or more. Urgent action is required to avoid approaching, let alone exceeding, the 2°C limit.”

Our research shows that if we exceed the 2°C global warming target, we will pay a high price in terms of biodiversity loss, jeopardizing the provision of ecosystem services on which we all rely for a living. The prevention of temperature overshoots should come first, followed by limiting the duration and magnitude of any overshoots.

Dr. Alex Pigot

The study examined over 30,000 species in locations around the world and discovered that the chances of returning to pre-overshoot ‘normal’ are either uncertain or non-existent in more than a quarter of the locations studied.

The paper focuses on one overshoot scenario in which CO2 emissions continue to rise until 2040, then fall into negative territory after 2070 due to deep carbon cuts and widespread deployment of carbon dioxide removal technology. This means that global temperature rise will exceed 2°C for several decades this century before falling below this level around 2100. The researchers investigated when and how quickly a species in a specific location would be exposed to potentially dangerous temperatures, how long that exposure would last, how many species would be affected, and whether they would ever be de-exposed and return to their thermal niche.

In line with previous research published in Nature*, the research team discovered that, for most regions, exposure to unsafe temperatures will occur suddenly as further warming causes many species to be pushed beyond their thermal niche limits at the same time. However, due to constantly volatile climatic conditions within local sites and long-term changes to ecosystems, the return of these species to conditions comfortably within their thermal niches will be gradual and will lag behind the global temperature decline. The effective overshoot for biodiversity risks is estimated to be between 100 and 130 years, roughly double the actual temperature overshoot of around 60 years.

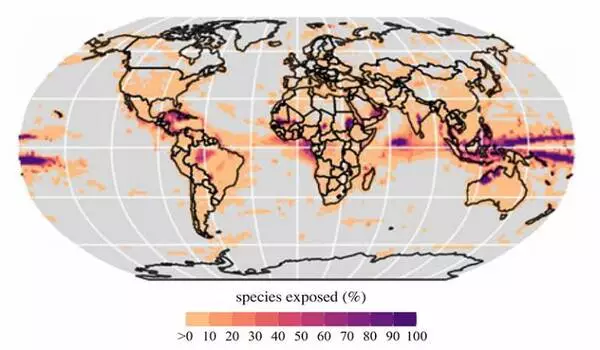

These threats primarily affect tropical regions, with over 90% of species in the Indo-Pacific, Central Indian Ocean, Northern Sub-Saharan Africa, and Northern Australia pushed outside of their thermal niches. Furthermore, in the Amazon, one of the world’s most species-rich regions, more than half of the species will be exposed to potentially dangerous climate conditions.

Concerningly, it is unknown whether the proportion of exposed species will ever return to pre-overshoot levels in about 19% of the total number of sites studied, including the Amazon. Furthermore, 8% of sites are expected to never return to those levels. This means that the overshoot can have irreversible effects on nature, such as species extinction and drastic changes in ecosystems.

Lead author Dr Andreas Meyer (African Climate and Development Initiative, University of Cape Town) said: “In the Amazon, this could mean replacement of forests with grasslands, and as a consequence, the loss of an important global carbon sink, which would have knock-on effects on multiple ecological and climatic systems as well as our ability to curtail global warming.”

The study emphasizes the importance of considering the entire picture of damage caused by overshoot scenarios, rather than focusing solely on ensuring the ‘final destination’ is within the agreed-upon temperature limits, which may understate the need for rapid and deep emissions reductions. Furthermore, the authors note that carbon dioxide removal technology itself is likely to have negative effects on ecosystems: large-scale forest planting or biofuels production, for example, require a lot of land and water and may even have secondary effects on the climate system.

Lead co-author Dr Joanne Bentley (African Climate and Development Initiative, University of Cape Town) said: “It is important to realise that there is no ‘silver bullet’ solution for mitigating climate change impacts. We have to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Many carbon dioxide removal technologies and nature-based solutions, such as afforestation, come with potential negative impacts.

“Our research shows that if we exceed the 2°C global warming target, we will pay a high price in terms of biodiversity loss, jeopardizing the provision of ecosystem services on which we all rely for a living. The prevention of temperature overshoots should come first, followed by limiting the duration and magnitude of any overshoots.”

According to co-author Christopher Trisos (University of Cape Town’s African Climate and Development Initiative), “Our findings are unambiguous. They should serve as a wake-up call that delaying emissions cuts will result in a temperature overshoot at an astronomical cost to nature and humans that unproven negative emission technologies will not be able to reverse.”