The researchers discovered that a silica surface, such as sand, has little effect on slowing the movement of the plastics, but that natural organic matter formed by the decomposition of plant and animal remains can either temporarily or permanently trap the nanoscale plastic particles, depending on the type of plastic.

The findings, which were published in the journal Water Research, could aid researchers in developing better methods for filtering and cleaning up pervasive plastics in the environment. Indranil Chowdhury, assistant professor in WSU’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Mehnaz Shams and Iftaykhairul Alam, recent civil engineering graduates, are among the researchers.

“We’re looking into developing a filter that’s more efficient at removing these plastics,” Chowdhury explained. “People have noticed micro and nanoscale plastics escaping into our drinking water, and our current drinking water system is insufficient to remove these micro and nanoscale plastics. This is the first fundamental examination of those mechanisms.”

Washington State University researchers have shown the fundamental mechanisms that allow tiny pieces of plastic bags and foam packaging at the nanoscale to move through the environment.

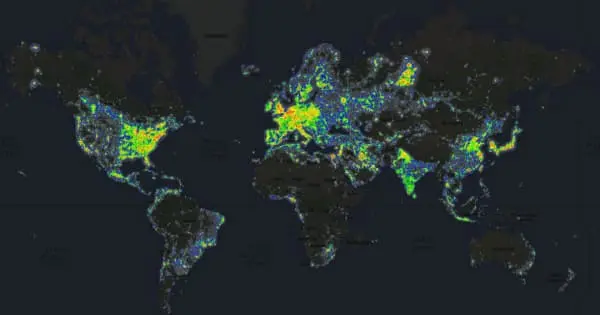

Plastics, which have been around since the 1950s, have properties that make them useful in modern society. They are water resistant, inexpensive, simple to manufacture, and useful for a wide range of applications. However, the accumulation of plastics is becoming a growing concern around the world, with massive patches of plastic garbage floating in the oceans and plastic waste appearing in the most remote areas.

“Plastics are a wonderful invention that is so simple to use, but they are extremely persistent in the environment,” Chowdhury explained.

Plastics degrade through chemical, mechanical, and biological processes to micro-and then nano-sized particles less than 100 nanometers in size after they are used. Despite the removal of micro and nanoscale plastics in some wastewater treatment plants, large amounts of micro and nanoscale plastics end up in the environment. According to Chowdhury, more than 90 percent of tap water in the United States contains nanoscale plastics, and a 2019 study found that people eat about five grams of plastic per week or the amount of plastic in a credit card. The health consequences of such environmental pollution are poorly understood.

“We don’t know the health effects, and the toxicity is still unknown,” Chowdhury said, “but we continue to drink these plastics every day.” The researchers studied the interactions with the environment of the tiniest particles of the two most common types of plastics, polyethylene, and polystyrene, as part of the new study to learn what might impede their movement. Polyethylene is a foamed plastic that is used in foam drinking cups and packaging materials, whereas polystyrene is a plastic that is used in plastic bags, milk cartons, and food packaging.

The researchers discovered that polyethylene particles from plastic bags move easily through the environment, whether they pass through a silica surface like sand or natural organic matter. Sand and plastic particles repel each other in the same way that like-poles of a magnet repel each other, so the plastic does not stick to the sand particles. Plastic particles cling to natural organic material, which is abundant in the natural aquatic environment but only for a short time. They are easily washed away by changing the chemistry of the water.

“That’s bad news for polyethylene in the environment,” Chowdhury explained. “It does not adhere to the silica surface very well, and if it adheres to the surface of natural organic matter, it can be re-mobilized. According to these findings, nanoscale polyethylene plastics may escape from our drinking water treatment processes, particularly filtration.”

The researchers discovered better news in the case of polystyrene particles. Organic matter, unlike a silica surface, was able to stop its movement. The polystyrene particles adhered to the organic matter and remained in place. The researchers hope that the findings will eventually aid in the development of filtration systems for water treatment facilities to remove nanoscale plastic particles.

Since scientists learned more about microplastic pollution in the oceans, they’ve been collaborating with governments and businesses to prevent more plastics from entering the sea. As a result, many soap companies, including big names like Unilever, Johnson & Johnson, and Proctor & Gamble, have been phasing microbeads out of many of their products in time for the ban. The ban does not apply to products that you apply to your skin, such as sunscreen and make-up.