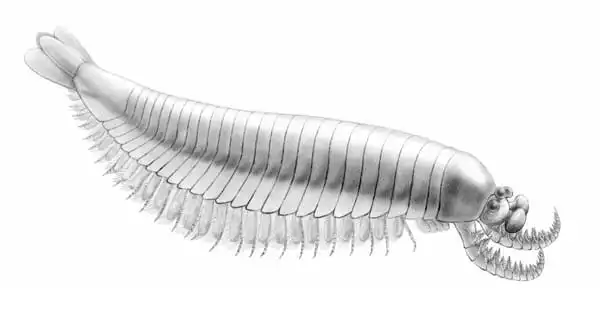

Opabinia regalis is an extinct stem-group arthropod discovered in British Columbia’s Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale Lagerstätte (505 million years ago). Opabinia was a soft-bodied animal with a segmented trunk and a fan-shaped tail that could grow up to 7 cm in length. The head has five eyes, a mouth under the head that faces backward, and a clawed proboscis that likely passed food to the mouth.

An international team of scientists has confirmed that a specimen previously thought to be a radiodont is, in fact, an opabiniid. The researchers used novel and robust phylogenetic methods to confirm Utaurora comosa as only the second opabiniid ever discovered, and the first in over a century.

The late Stephen Jay Gould, a former professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard, popularized the “weird wonder” stem-group arthropods Opabinia and Anomalocaris discovered in the Cambrian Burgess Shale in his book Wonderful Life, making them icons in popular culture. While the “terror of the Cambrian” Anomalocaris is a radiodont with many relatives, the five-eyed Opabinia, with its distinctive frontal proboscis, is the only opabiniid ever discovered. Until now, that is.

An international team of scientists led by Harvard University has confirmed that a specimen previously thought to be a radiodont is actually an opabiniid. The new study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, used novel and robust phylogenetic methods to confirm Utaurora comosa as only the second opabiniid ever discovered, and the first in more than a century.

The preliminary phylogenetic analysis revealed that it was most closely related to Opabinia. We followed up with more tests to interrogate that result using different evolutionary models and data sets to visualize the various types of relationships this fossil may have had.

Jo Wolfe

Utaurora comosa, discovered in the 500 million-year-old middle Cambrian Wheeler Formation of Utah, was first described as a radiodont in 2008. Stephen Pates, co-lead author and former postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology (OEB) at Harvard, first encountered the specimen as a graduate student at the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute & Natural History Museum. Pates was researching the diversity of radiodonts when he noticed this specimen did not appear to be a true radiodont. Pates worked with co-lead author Jo Wolfe, a postdoctoral fellow in OEB who studies the relationships of fossil and living arthropods, to determine where Utaurora fit in the tree of life after joining senior author Professor Javier Ortega-lab Hernández’s in OEB.

Opabiniids are the first group of animals to have a mouth that faces the back. Their dorsal intersegmental furrows foreshadow full body segmentation, while their lateral swimming flaps foreshadow appendages. Utaurora has characteristics and morphology in common with both radiodonts and Opabinia. While the anterior structure and eyes of Utaurora were poorly preserved – Opabinia is best known for its frontal proboscis and five eyes – the intersegmental furrows along the back and the paired serrated spines on the tail were fully visible.

Pates and Wolfe used phylogenetic analysis to compare Utaurora to 43 fossils and 11 living taxa of arthropods, radiodonts, and other panarthropods due to limited morphological observations.

“The preliminary phylogenetic analysis revealed that it was most closely related to Opabinia,” Wolfe explained. “We followed up with more tests to interrogate that result using different evolutionary models and data sets to visualize the various types of relationships this fossil may have had.”

Opabinia was discovered in the Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia, Canada, whereas Utaurora was discovered in Utah and, while still Cambrian, is a few million years younger than Opabinia. “This means Opabinia wasn’t the only opabiniid, and Opabinia wasn’t as unique a species as we thought,” Pates explained.

When Utaurora was first described as a radiodont in 2008, scientists assumed that opabiniids and radiodonts belonged to a monophyletic group known as ‘dinocarids.’ However, scientists have discovered over ten new species of radiodonts in the last 10 to 15 years, demonstrating that opabiniids and radiodonts are not the same.

“We also have more phylogenetic tools to examine our findings,” Pates added. “Based on the morphology alone, you could argue that Utaurora is a strange radiodont and that the ‘dinocarid’ concept should be revived. However, our phylogenetic dataset and analyses supported Utaurora as an opabiniid in 68 percent of the trees retrieved by data analysis, but only in 0.04 percent of the trees “or even a radiodont.”

“The discovery of Wonderful Life and the description of these fossils occurred prior to current evolutionary paradigms. The similarities between Opabinia and Anomalocaris were not fully appreciated at the time “Wolfe stated. “We now know that these animals represent extinct evolutionary stages that are related to modern arthropods. We also have tools that go beyond qualitatively comparing morphological features to determine a more definitive placement within the animal tree of life.”