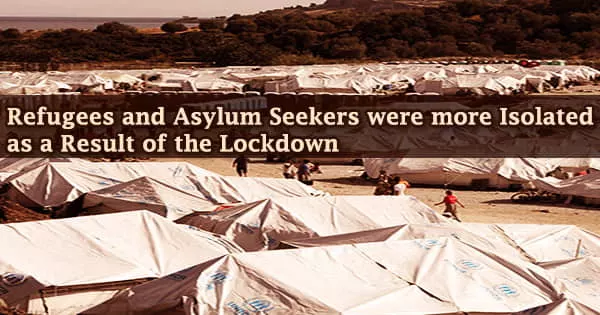

People who have fled war, violence, conflict, or persecution and crossed an international boundary in search of safety in another country are known as refugees. They’ve often been forced to run with nothing more than the clothes on their backs, abandoning their homes, belongings, jobs, and loved ones behind.

The term “asylum seeker” refers to someone whose application for asylum has yet to be processed. Approximately one million people seek refuge each year. Throughout 4.2 million people around the world were awaiting a judgment on their asylum petitions at the end of 2019.

According to Newcastle University academics, the first COVID-19 lockdown had a considerable negative impact on refugees and asylum seekers. Because they were required to stay at home, most were unable to visit the actual locations of support groups that give refugees and asylum seekers with information, assistance, and education.

As a result, many people felt more alone and lonely as a result of this. This was especially true for single moms with young children and single males who had been attempting to apply for asylum for several years and were already alone and without support networks.

Despite the sector’s positive response, which moved quickly and effectively to make services available online, digital inequality and a lack of access to smartphones, computers, or televisions meant that many refugees and asylum seekers were unable to access the online spaces that became critical for connectivity and wellbeing during the pandemic.

This wasn’t only due to their low income; it was exacerbated by Home Office procedures that hinder refugees and asylum seekers from accessing broadband or opening bank accounts.

The research has been published in a new report, “It’s like rubbing salt on the wound: the impacts of COVID-19 and lockdown on asylum seekers and refugees.”

Challenges and inequalities

Dr. Robin Finlay, co-author of the report, and a Research Associate in Newcastle University’s School of Geography, Politics, and Sociology, said: “For asylum seekers and refugees, the impacts of COVID-19 overlap with a range of challenges and inequalities that pre-date the pandemic. Many of the refugees and asylum seekers we spoke to said that their lives were already in a state of lockdown before the pandemic as they faced restrictions in several areas such as housing, education, finance, and employment. What the research shows is the pandemic has intensified the hostility of the already hostile environment.”

For asylum seekers and refugees, the impacts of COVID-19 overlap with a range of challenges and inequalities that pre-date the pandemic. Many of the refugees and asylum seekers we spoke to said that their lives were already in a state of lockdown before the pandemic as they faced restrictions in several areas such as housing, education, finance, and employment. What the research shows is the pandemic has intensified the hostility of the already hostile environment.

Dr. Robin Finlay

Peter Hopkins, Professor of Social Geography and co-author of the report, noted: “The closure of community spaces, which provide asylum seekers and refugees with a crucial way to develop a sense of local inclusion as well as being important for wellbeing, exacerbated the already high rates of social isolation and poor mental health experienced by this group.”

In Glasgow, Newcastle, and Gateshead, the research team interviewed 50 refugees and asylum seekers aged 19 to 50 from a variety of nations and regions, including Sudan, Nigeria, Syria, and Iraq.

A female asylum seeker from the Middle East said: “Before COVID, I used to attend community groups, especially the Kurdish Women’s Group. Coming to the UK I felt really alone and depressed because I felt isolated. But that group was open, and I could meet my fellow people the people who spoke my language and my mind was kind of away from all the stuff that I had left back home.”

“But now, I don’t have this and it’s dragging me down even more. I used to go there a lot, we used to do activities and talk about mental health, English classes, but now I am just home alone. It’s really hard.”

Chronic lack of funding

The researchers also spoke with 20 refugee and asylum-seeking organizations and conducted a nationwide poll of over 100 service providers, ranging from tiny organizations with a few employees to larger agencies with offices across the UK. Many groups indicated they had to stop providing services in person and relocate them online in order to continue to provide support.

As a result of the limited employment opportunities for asylum seekers and refugees, many volunteers with service providers, and some organizations the researchers spoke with are managed by refugees or have personnel with refugee backgrounds in significant positions. More than two-thirds (67%) of the service providers polled felt their volunteers were instrumental in their pandemic response.

Some organizations discussed how they established weekly doorstep visits, including grocery delivery, as a way to keep in touch with refugees and asylum seekers, while others said they offered devices, internet data, as well as clothes, furniture, and books.

Despite this, the research team found that only 39% of respondents were convinced that their organization had the resources it needed to support them during the pandemic, indicating a chronic lack of funding in the sector.

Overall, service providers claimed the epidemic had forced them to find new methods of working, with 60% stating they had achieved long-term improvements as a result.

“Those providing services for refugees and asylum seekers responded to the pandemic in a positive and flexible manner and stepped in to ensure they provided critical services as well as supporting the wellbeing of their staff and volunteers, highlighting the incredible commitment and dedication of their staff,” said Dr. Matthew Benwell, co-author of the report and Senior Lecturer in Human Geography.

However, we discovered that the vast majority of groups were highly concerned about the pandemic’s ongoing impact and the absence of government support for asylum seekers and refugees, despite already restricted resources.