Many people may believe that tuberculosis (TB) is a condition from a bygone period. But it continues to claim more than a million deaths annually. The organism that causes TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is continuing to develop antibiotic resistance, which is making the issue worse.

Currently, scientists at San Diego State University have discovered uncommon genetic markers in M. tuberculosis that may enhance early detection of drug-resistant forms of the illness and aid in their prevention.

Searching for elusive variants

Clinicians cultivate samples of respiratory tract mucus and bombard them with antibiotics to determine if a patient has a strain of TB that is resistant to conventional treatment.

“But because TB grows so slowly, that takes weeks,” said San Diego State University professor of public health Faramarz Valafar. “In those weeks that patient is going around spreading TB that might be antibiotic-resistant.”

He claims the use of molecular diagnostic technologies is quicker. These test for typical genetic indicators of drug resistance and enable earlier therapy. However, TB strains with uncommon resistance mechanisms continue to evade molecular detection.

“They don’t have the common genetic markers, but they are resistant,” said Valafar. This leads clinicians to incorrectly conclude that standard TB drugs will kill the bacteria. “And so the patient is given the wrong medications and continues to infect others for weeks sometimes months before they realize that these drugs aren’t working. So we really want to prevent that.”

The search for uncommon genetic changes linked to resistance was headed by Derek Conkle-Gutierrez, a doctoral student in Valafar’s group. Samples of M. tuberculosis were gathered by the researchers from seven distinct nations where antibiotic resistance is widespread. Even though molecular diagnostics had missed some of the drug resistance in the samples, culture had shown that some of it existed.

“First we confirmed that they didn’t have the known markers and then we started looking for what other mutations are showing up exclusively in these unexplained resistant isolates,” said Conkle-Gutierrez.

The fear is that other pulmonary infections like COVID could overwhelm the immune system and trigger TB to go into its active phase. If this happens, TB will become a bigger problem in the Western world as well. We have already seen this in HIV co-infections. Even though HIV is not a pulmonary disease, because it weakens the immune system, it leads to activation of TB. Most patients who have HIV die from TB and not HIV.

Faramarz Valafar

The researchers discovered one group of uncommon genetic changes that may assist in preventing the common TB medicine kanamycin from hindering the virus’s capacity to generate the proteins it requires, leaving it harmless to the pathogen. The anti-TB medicine capreomycin may experience the same effects due to further mutations.

The study is published in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

“This manuscript identifies potential markers; confirmatory work for the selection of markers for the next generation of more comprehensive molecular diagnostic platforms lies ahead,” said Valafar.

“He says given the evolution of antibiotic resistance, molecular diagnostics will need to be updated frequently and be tailored to different regions of the world where antibiotic resistance in TB is common,” Conkle-Gutierrez agrees.

It takes a lot of time and money to go in and truly seek for these inexplicable cases, bring them in, and sequence them, but it’s necessary to do so in order to locate them and prevent them from spreading and leading to additional antibiotic resistance that goes unnoticed.

The widespread use of life-saving antibiotics may have revolutionized medicine, but bacterial diseases like M. tuberculosis swiftly developed resistance to them, as researchers discovered during the 20th century.

This is due to the fact that the bacteria strains that withstand the assault of these potent medications include modifications that enable them to endure and proliferate. The use of antibiotics in cattle and for non-bacterial diseases in people, such as those brought on by viruses, exacerbates this.

Tuberculosis is close to home

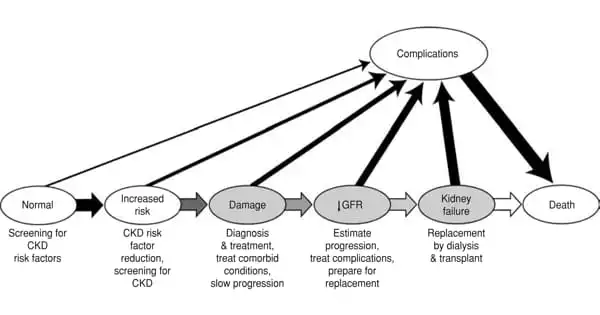

A quarter of the world’s population is thought to be affected by TB, which has two stages: latent and active. The immune system of the body controls the bacterial burden, thus the majority of people remain in the latent phase.

They continue to be symptom-free and are not spreadable. Of those infections, about 10% develop into active TB. After that, patients start to exhibit symptoms and spread the illness to others.

“It is a very important public health concern for the United States as well,” said Valafar, who says many people in this country have latent TB.

“The fear is that other pulmonary infections like COVID could overwhelm the immune system and trigger TB to go into its active phase. If this happens, TB will become a bigger problem in the Western world as well. We have already seen this in HIV co-infections. Even though HIV is not a pulmonary disease, because it weakens the immune system, it leads to activation of TB. Most patients who have HIV die from TB and not HIV.”

In the end, there is a dire need for a TB vaccination. Up till then, reducing morbidity requires better molecular diagnostics for the diagnosis of antibiotic resistance. In order to accomplish this, a funding has been been awarded to Valafar’s lab to directly sequencing drug-resistant TB from infected lung tissue.

“And that will really break through some barriers that the tuberculosis research community has been facing,” he said.