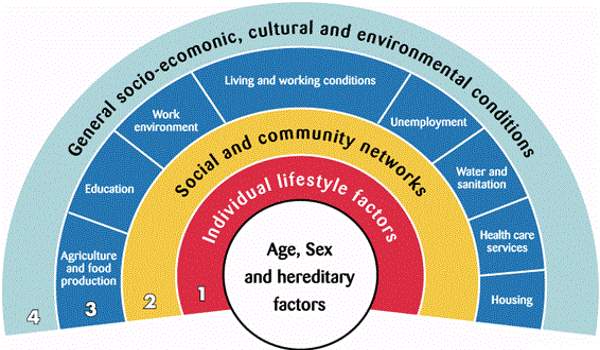

If health is a causal factor in economic status and spreads from generation to generation, it may have an impact on intergenerational mobility. Genetics, parental behaviors, and the home environment, or a combination of these factors, can all pass on health from parent to child.

Epidemiologists — scientists who study population health — don’t just mean poverty when they say there’s more inequality. Poverty and poor health go hand in hand. However, epidemiological research shows that high levels of inequality have a negative impact on the health of even the wealthy, primarily because, according to researchers, inequality reduces social cohesion, a dynamic that leads to increased stress, fear, and insecurity for everyone.

A new study finds that structural racism, as measured by the racial economic mobility gap between Black and White people with similar parental income (as an indicator of similar childhood socioeconomic status), is strongly associated with Black-White mortality disparities in the United States, both in a recent birth cohort and across all ages. These findings, published in Cancer Epidemiology, indicate that the effects of structural racism on mortality have persisted in a similar magnitude across generations over the last century.

A new study suggests structural racism measured by the racial economic mobility gap between Black and White persons with a similar parental income is strongly associated with Black-White disparities in mortality in the USA, both in a recent birth cohort and in all ages combined.

Social inequalities and discriminatory policies based on race/ethnicity, also known as structural racism, are major contributors to health disparities. Structural racism can have a negative impact on the economic, social, service, and physical living environments, resulting in fewer educational and job opportunities, lower-income, poorer housing, transportation, and public safety, food insecurity, and limited health care.

This is one of the few studies that looks at the link between structural racism and death from a variety of causes. Researchers from the American Cancer Society, led by Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, examined county-level data on economic mobility and death from all causes, heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), injury/violence, all malignant cancers, and 14 cancer types in all ages combined, as well as all-cause mortality in people aged 30-39 years. Data for the 30-39 year age group covered 69 percent of individuals in that age group nationally, and data for all ages combined covered 82 percent to 90 percent of the U.S. population.

“While more research is needed to identify the factors mediating these associations and appropriate interventions to mitigate them, equitable and widespread implementation of proven interventions to increase health equity, such as equitable access to care and preventive measures, can help reduce health disparities,” Dr. Islami said.

If the economic status into which a child is born influences her health, which in turn influences economic status in adulthood, health could affect intergenerational mobility. There are various hypotheses regarding how health at a young age may affect health—and possibly educational or employment—outcomes later in life.

Death rates in the United States are higher among non-Hispanic Black (Black) people than among non-Hispanic White (White) people, according to the findings. Based on data from 471 counties, a one percentile increase in the economic mobility gap was associated with a 6.8 percent increase in the Black-White mortality gap among males and a 10.7 percent increase in the Black-White mortality gap among females aged 30-39 years.

Based on data from 1,572 counties, the corresponding percentages for males were 10.2 percent and 14.8 percent for females, equating to an increase in the mortality gap of 18.4 and 14.0 deaths per 100,000, respectively. Similarly, for major causes of death, such as COPD, injury/violence, and cancers of the lung, liver, and cervix, strong associations between economic mobility gap and mortality gap were found at all ages.

“Dismantling structural racism will necessitate increased efforts to implement meaningful institutional changes, as well as broad societal engagement to create equitable local, state, and federal policies,” the authors write. “The findings of this study could help advocate for and inform public policies to improve equity, as well as establish a benchmark for measuring progress in reducing structural racism and its negative health effects.”

Several studies’ evidence suggests that there is a link between income inequality and health and social problems. Further correlation analysis, however, would be beneficial in testing how sensitive the findings are to: different measures of social stratification; different measures of income inequality; variations in the countries chosen; and the treatment of outliers.