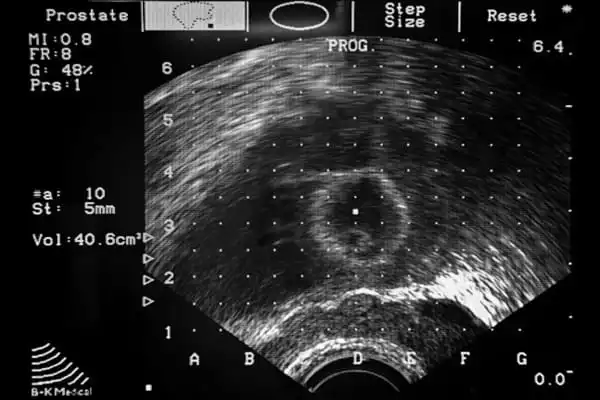

A prostate ultrasound is frequently used to diagnose prostate cancer early on. Prostate cancer is one of the most prevalent types of cancer in males and occurs in the prostate, a tiny gland that produces seminal fluid. According to new research, an ultrasound scan can be used to detect occurrences of prostate cancer.

In a clinical experiment involving 370 men, researchers from Imperial College London, University College London, and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust discovered that a novel form of ultrasound scan may accurately diagnose most prostate cancer cases.

When compared to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, ultrasound scans missed only 4.3 percent more clinically significant prostate cancer cases (cancer that should be treated rather than monitored).

MRI scans are both costly and time-consuming. The team believes that an ultrasound scan should be utilized as a first test in a community healthcare environment, as well as in poor and middle-income nations where high-quality MRI scans are difficult to obtain. They believe it might be used in conjunction with existing MRI scans to improve cancer detection. The study was published in the journal Lancet Oncology.

“Prostate cancer is the most often diagnosed malignancy in the UK,” said Professor Hashim Ahmed, main author of the study and Chair of Urology at Imperial College London. One in every six males will be diagnosed with the condition at some point in their lives, and that number is anticipated to climb.

Our research is the first to demonstrate that a certain type of ultrasound scan might be utilized as a prospective test for detecting clinically significant cases of prostate cancer. Although MRI scans are slightly superior, they can detect most cases of prostate cancer with high accuracy.

Professor Hashim Ahmed

“MRI scans are one of the tests we employ to diagnose prostate cancer.” Although successful, these scans are costly, take up to 40 minutes to complete, and are not widely available. In addition, some individuals, such as those with hip replacements or claustrophobia, are unable to have MRI scans. As cancer waiting lists grow as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an urgent need for more efficient and less expensive tests to diagnose prostate cancer.

“Our research is the first to demonstrate that a certain type of ultrasound scan might be utilized as a prospective test for detecting clinically significant cases of prostate cancer. Although MRI scans are slightly superior, they can detect most cases of prostate cancer with high accuracy. We believe that this test can be employed in low and middle-income regions where access to pricey MRI equipment is limited and prostate cancer cases are increasing.”

With around 52,300 new cases diagnosed each year, prostate cancer is the most frequent cancer in men in the UK. It occurs when cells in the prostate proliferate uncontrollably. Prostate cancer progresses slowly, and symptoms such as blood in the urine do not present until the disease has progressed. Males over the age of 50 are more likely to be affected, as are men with a family history of the disease. Black males are disproportionately affected by the disease, and prostate cancer mortality have already surpassed those from breast cancer.

A unique sort of magnetic resonance Imaging (MRI) scan called a multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) scan, which helps doctors identify if there is any cancer inside the prostate and how quickly the cancer is expected to grow, is one of the key tools for diagnosing prostate cancer. However, the scan takes 40 minutes and costs between £350 and £450.

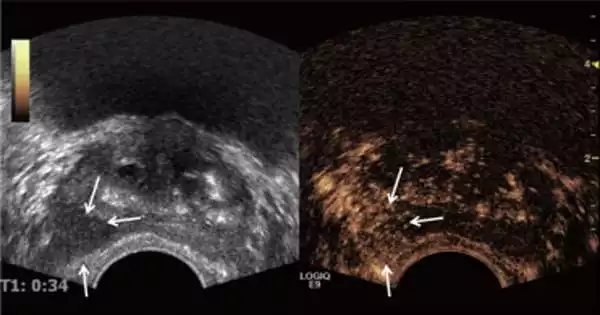

The current study looked at the use of a different type of imaging termed multiparametric ultrasound (mpUSS), which examines the prostate using soundwaves. To create images of the prostate, a device called a transducer is used in the test. It is inserted into the rectum and emits sound waves that reverberate off organs and other structures. These are then made into pictures of the organs.

The doctor performing the test additionally employs extra-special sorts of ultrasound imaging that assess the stiffness of the tissue as well as the amount of blood flow it has. These techniques are known as elastography, doppler, and contrast-enhancement with microbubbles. Cancers appear more plainly as they get more thick and have a higher blood supply. Although mpUSS is more commonly available than mpMRI, no large-scale research have been conducted to evaluate its usefulness as a test for detecting prostate cancer cases.

The team recruited 370 men at risk of prostate cancer for the new trial, named cancer diagnosis by multiparametric ultrasonography of the prostate (CADMUS). They were discovered after early testing such as a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, a blood test used to diagnose prostate cancer, and/or an abnormal digital rectal examination, which examines a person’s lower rectum, pelvic, and lower abdomen.

Between March 2016 and November 2019, the study was conducted at seven hospitals in the United Kingdom, including the principal site Charing Cross Hospital, which is part of the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust.

At different trips, the males had both mpUSS and mpMRI scans. This was followed by biopsies for 257 patients who had a positive mpUSS or mpMRI test result, which involved utilizing fine needles to extract small samples of tissue from the prostate to analyze under a microscope for malignancy. The findings of the tests were then compared by the team.

Malignancy was found in 133 men, with 83 of them having clinically serious cancer. Individually, mpUSS detected 66 cases of clinically serious cancer against 77 cases discovered by mpMRI.

Although mpUSS found 4.3% fewer clinically significant prostate tumors than mpMRI, the researchers estimated that this approach would result in 11.1% more individuals being biopsied. This was due to the mpUSS occasionally detecting abnormal spots even when there was no malignancy.

The researchers feel that the test can be utilized as an alternative to mpMRI as a first test for people at risk of prostate cancer, especially in cases when mpMRI is not possible. Because both imaging methods missed clinically significant malignancies found by the other, utilizing both would boost the diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancers when compared to using either test alone.

“Our results provide an accurate test for prostate cancer in people who were previously without one using a scan that is affordable and straightforward to do,” stated first author Dr Alistair Grey (UCL Division of Surgery & Interventional Science).