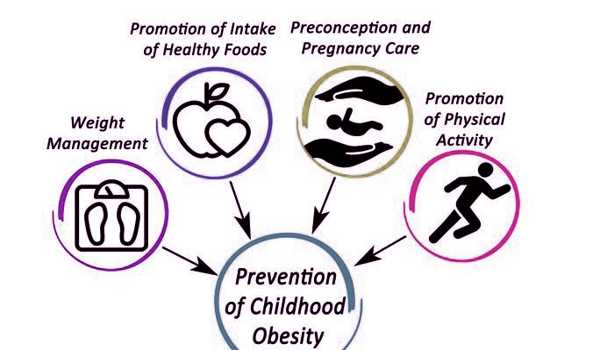

Typically, interventions to prevent childhood obesity do not focus on the first 1,000 days of life, a critical period during which environmental and nutritional cues can increase the risk of obesity. A new study shows that changing parents’ health behaviors and the way clinicians care for mothers and infants reduces excess weight gain in infants.

Childhood obesity rates in the United States are at an all-time high, but there are few interventions that promote healthy weight gain in children from infancy to age two – a critical period for the development and prevention of childhood obesity. A new study published in Pediatrics discovered that when low-income pregnant women received individualized health coaching in tandem with clinicians in community health centers and public health programs systematically changing how they delivered care to women and their infants, fewer infants gained excess weight.

“The majority of interventions to prevent childhood obesity attempt to change the behavior of the child’s parent or family,” says lead author Elsie Taveras, MD, MPH, chief of the Division of General Academic Pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). “However, a child’s health is also influenced by how well clinical and public-health systems interact with families and provide obesity-prevention care.”

A new study demonstrates how changing parents’ health behavior and how clinicians deliver care to mothers and infants decreased excess weight gain in infants.

Because it reaches all women and infants, the novel intervention known as the First 1,000 Days program has the potential to have a much broader impact on childhood obesity. “We can be much more effective at preventing childhood obesity if all obstetricians pay close attention to a woman’s excess weight gain during pregnancy and all pediatricians are trained in identifying problematic weight gain in infants, for example,” says Taveras, a professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School (HMS). The First 1,000 Days program is also unique in that it combats childhood obesity beginning in the first trimester of pregnancy and focuses on low-income families, who have the highest risk of obesity in children.

The researchers compared the weight outcomes of infants in women and infants who received the intervention versus those who received standard care. The intervention group consisted of 995 pregnant women in their first trimester and their infants who were being treated at two community health centers affiliated with Mass General Brigham. The control group included 650 pregnant women and their infants who received standard care at two other community health centers that served low-income patients.

The intervention had two goals: to encourage women and their infants to adopt healthy behaviors and to make systematic changes in the clinical care the women and infants received. The intervention’s systems-level components included, for example, standardizing obesity-prevention training for pediatric clinicians and staff, closely monitoring infant weight gain, screening pregnant women for adverse health behaviors and social determinants of health, and providing educational materials and text messages to families that promoted healthy feeding and sleeping habits of children.

In addition, women in the intervention group received individual support and coaching during pregnancy and the first six weeks postpartum on diet, physical activity, sleep and stress reduction.

Infants in the intervention group had a 54% lower risk of being overweight at six months and a 40% lower risk of being overweight at 12 months when compared to infants who received standard infant care. The children will be followed by the researchers until they are two years old. At six weeks postpartum, mothers at the intervention sites had slightly lower, but clinically insignificant, weight retention than mothers receiving standard care. However, more women in the intervention group had a postpartum visit with a primary care clinician than women in the control group.

“The first six weeks after delivery are critical for positively influencing a woman’s health trajectory,” Taveras says. “We may need a more robust intervention to achieve postpartum weight loss.”

Taveras adds that changing care systems has the potential to improve the health of all women and their babies at community health centers and public health programs. “We believe that by going beyond simply changing individual behaviors and risk factors, one parent at a time, we can achieve long-term reductions in childhood obesity.”

The research team will now look for the best ways to disseminate the intervention to other health systems that serve low-income families, as well as train frontline clinicians on how to incorporate the program for preventing childhood obesity into their practices. The Boston Foundation and the National Institutes of Health provided significant funding for this study.