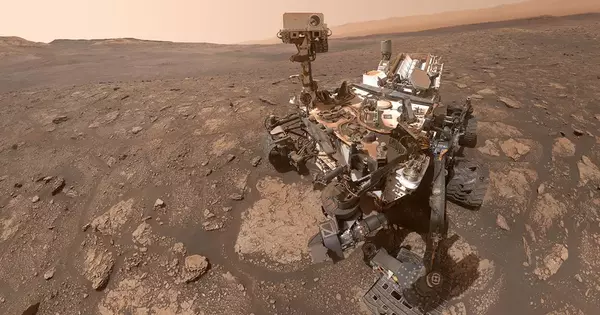

According to scientists, the first audio recordings from Mars reveal a quiet planet with occasional gusts of wind where two different speeds of sound would have a strange delayed effect on hearing. After NASA’s Perseverance rover landed on Mars last February, its two microphones began recording, allowing scientists to hear what it’s like on Mars for the first time. The scientists published their first analysis of the five hours of sound picked up by Perseverance’s microphones in the journal Nature.

The acoustic environment of Mars has been recorded for the first time by NASA’s Perseverance rover, which has been surveying the Red Planet’s surface since February 2021. An international team1, led by Paul Sabatier, an academic at the University of Toulouse III, and including scientists from the CNRS and ISAE-SUPAERO, analyzed the sounds, which were obtained using the SuperCam instrument built in France under the authority of the French space agency CNES.

Perseverance first recorded sounds from Mars on February 19, 2021, the day after it arrived. These sounds are audible to humans and range between 20 Hz and 20 kHz. First and foremost, they reveal that Mars is quiet, so quiet that the scientists mistook the microphone for broken on several occasions.

Paul Sabatier

For 50 years, interplanetary probes have returned thousands of striking images of the surface of Mars, but never a single sound. Now, NASA’s Perseverance mission has put an end to this deafening silence by recording the first ever Martian sounds. The scientific team1 for the French-US SuperCam2 instrument installed on Perseverance was convinced that the study of the soundscape of Mars could advance our understanding of the planet. This scientific challenge led them to design a microphone dedicated to the exploration of Mars, at ISAE-SUPAERO in Toulouse, France.

Perseverance first recorded sounds from Mars on February 19, 2021, the day after it arrived. These sounds are audible to humans and range between 20 Hz and 20 kHz. First and foremost, they reveal that Mars is quiet, so quiet that the scientists mistook the microphone for broken on several occasions. Aside from the wind, it is obvious that natural sound sources are scarce.

The audio revealed previously unknown turbulence on Mars, according to Sylvestre Maurice, the study’s main author and scientific co-director of the shoebox-sized SuperCam mounted on the rover’s mast, which houses the main microphone.

The international team listened to flights by the tiny Ingenuity helicopter, a sister craft to Perseverance, and heard the rover’s laser zap rocks to study their chemical composition — which made a “clack clack” sound, Maurice told AFP.

In addition to this investigation, the scientists focused on the sounds generated by the rover itself3, including the shock waves produced by the impact of the SuperCam laser on rocks, and flights by the Ingenuity helicopter. By studying the propagation on Mars of these sounds, whose behaviour is very well well understood on Earth, they were able to accurately characterise the acoustic properties of the Martian atmosphere.

The researchers show that the speed of sound is lower on Mars than on Earth: 240 m/s, as compared to 340 m/s on our planet. However, the most surprising thing is that it turns out that there are actually two speeds of sound on Mars, one for high-pitched sounds and one for low frequencies. Sound attenuation is greater on Mars than on Earth, especially for high frequencies, which, unlike low frequencies, are attenuated very quickly, even at short distances.

All of these factors would make it difficult for two people standing only five metres apart to have a conversation. They are caused by the composition of the Martian atmosphere (96 percent CO2, compared to 0.04 percent on Earth) and the extremely low atmospheric surface pressure (170 times lower than on Earth).

After one year, a total of five hours of acoustic environment recordings have been obtained. An in-depth analysis of these sounds has revealed the sound produced by the turbulence of the Martian atmosphere. The study of this turbulence at scales 1000 times smaller than anything previously known should improve our understanding of the interaction of Mars’ atmosphere with its surface. In the future, the use of other robots equipped with microphones could help us to better understand planetary atmospheres.