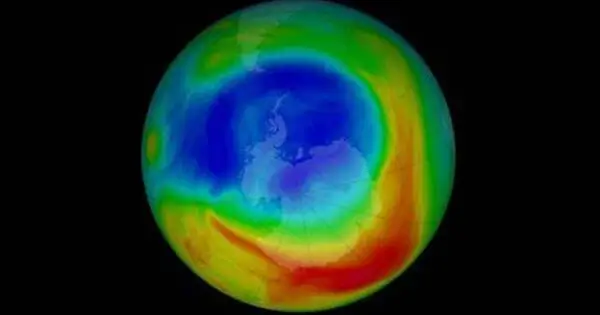

Ozone depletion is the thinning of the ozone layer in the Earth’s stratosphere. It consists of two connected processes seen since the late 1970s: a constant decline of roughly 4% in the total amount of ozone in Earth’s atmosphere, and a substantially bigger springtime decrease in stratospheric ozone (the ozone layer) around Earth’s polar regions. The latter event is known as the ozone hole. In addition to stratospheric occurrences, there are springtime polar troposphere ozone depletion events.

The ozone layer is critical because it absorbs the majority of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation, preventing it from reaching the Earth’s surface and causing a variety of health problems in humans, including skin cancer, cataracts, and immune system suppression, as well as damage to ecosystems and marine life.

Causes

The principal source of ozone depletion is the emissions of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), halons, and other ozone-depleting chemicals (ODS) into the atmosphere. These compounds were widely utilized in refrigeration, air conditioning, foam blowers, and aerosol propellants. When released into the atmosphere, they ascend to the stratosphere and are degraded by UV radiation, producing chlorine and bromine atoms. These atoms subsequently interact with ozone molecules, breaking them apart and contributing to ozone depletion.

Ozone depletion and the ozone hole are mostly caused by manmade chemicals, particularly halocarbon refrigerants, solvents, propellants, and foam-blowing agents (chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), HCFCs, halons), also known as ozone-depleting substances (ODS). These compounds are carried into the stratosphere via turbulent mixing after being emitted from the surface, which occurs far quicker than the molecules can settle. When they reach the stratosphere, they liberate atoms from the halogen group via photodissociation, catalyzing the breakdown of ozone (O3) into oxygen (O2). Both types of ozone depletion were shown to grow as halocarbon emissions rose.

How to Recover

The discovery of the ozone hole above Antarctica in the 1980s drew global attention to the issue of ozone destruction. In response, the international community acted, resulting in the Montreal Protocol, an international convention signed in 1987. The Montreal Protocol sought to phase out the manufacture and use of ozone-depleting chemicals. It has been widely recognized as a success since it has resulted in a significant reduction in atmospheric concentrations of these hazardous substances, allowing the ozone layer to gradually rebuild.

While the ozone layer appears to be recovering, there are still problems ahead. Some ozone-depleting compounds have lengthy atmospheric lives, which means they can remain in the atmosphere for many years. Additionally, there is ongoing monitoring and research to understand the interactions between ozone depletion and other environmental factors, such as climate change. Continued international cooperation and vigilance are necessary to ensure the protection and recovery of the ozone layer.