Despite dating from 200,000-160,000 years ago, the partially patched together skull of an early human possesses a brain capacity at the greater end of modern standards. The discovery suggests that huge brains appeared sooner than previously thought, though it is unclear what this means for intellect. The skull’s owner’s species is unknown, but it’s likely that this is the first Denisovan skull ever discovered, marking a significant step forward in our understanding of this fascinating population.

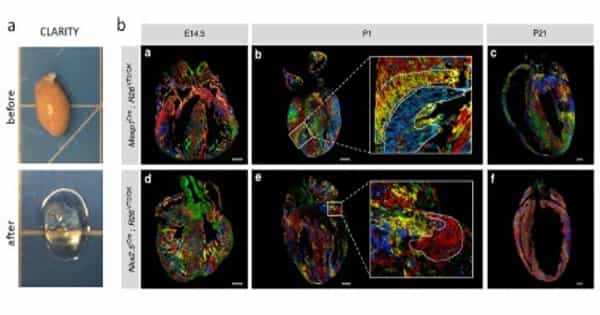

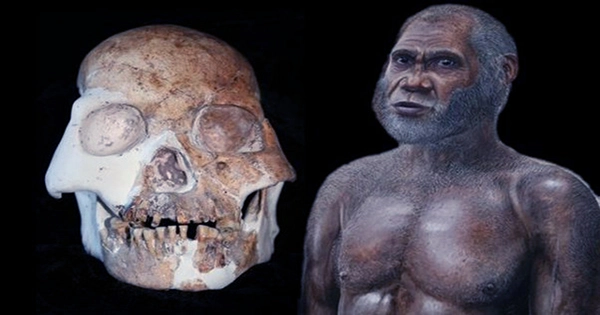

The 21 hominid fossil fragments have discovered at a location near Xujiayao, northern China, during the 1970s. They estimated to come from at least ten persons based on their ages and the bones discovered, making it impossible to group those with a similar source. However, a team led by Dr. Xiu-Jie Wu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences re-examined three fragments of skull from the Xujiayao site and found that they are almost probably from the same individual, according to a research published in the Journal of Human Evolution. Despite the fact that some components are missing, the three fragments precisely aligned at various spots (as seen above).

According to Wu, this could only do with CT scans, which were not accessible at the time of the discovery. They cover the majority of the back of a skull, providing a solid indication of overall skull capacity. It is impossible to measure cranial capacity correctly from incomplete skulls, especially when working with a species we do not know much about. “The shape of the modern human skull is more rounded/ encephalized with different proportions than in other Homo taxa,” according to the report. Because we do not know what the front of this person’s head looked like, there is certain to be some uncertainty.

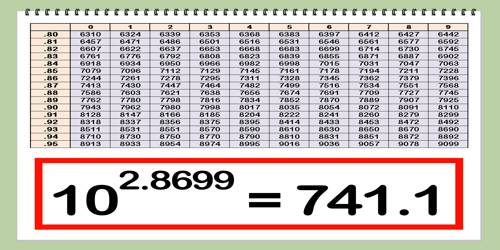

Nonetheless, Wu and co-authors conclude that the brain capacity was 1,700 cm3, which is more than the average for a modern human. The person in issue is thought to have been an adolescent boy, who Wu told IFLScience “should be quite near to an adult” while still having some growing to go. No one can be positive of the skull’s species without DNA from Xujiayao or matching skull sections from other sites. However, Wu told IFLScience that she believes it came from a Denisovan for two reasons. Not only do the ages match, but also “both Xujiayao and Xuchang have mosaic traits of Neanderthals, Asian archaic, and modern humans,” much like a Denisovan would.

Only a few teeth and bone fragments from the Denisova Cave in Siberia, from which the species derives its name, and a jawbone recovered high on the Tibetan Plateau, provide physical proof of Denisovans. The discovery of a portion of a skull that shows brain size adds to our knowledge of this intriguing branch of the human family tree. Australopithecine brain sizes expanded slowly over the 2 billion years they lived, but this trend accelerated with the emergence of the genus Homo. Nonetheless, exceptions have appeared to what was once thought to be a straightforward pattern of growing skull size.

Because their brain sizes matched an earlier epoch, Homo naledi once assumed too be much older than its 300,000-400,000 years. Similarly, Homo floresiensis, the relatively recent “hobbits,” were small-brained by today’s standards. The Xujiayao skull looks to be the polar opposite of the Xujiayao skull, with a brain size that is more modern than the ice age before last.

We cannot tell if the man in issue was an outlier or if he came from a species at least as big-brained as we did because we only have a single, partial skull. The original Homo sapiens skulls, dating back more than 300,000 years, were much smaller, measuring 1,300-1,400 cm3. Anthropologists are fascinated by brain size since it serves as a proxy for intelligence to some extent.

The match, though, is not ideal. Blue whales would be orders of magnitude smarter than dolphins if they had larger brains to conduct the same work. In order to adapt to cold conditions, brains can generate more insulation, which increases the size of the skull without adding any intelligence. The Denisovans lived in frigid climates, and the bones we have from them are large, thus their intelligence may have exaggerated by their head size.