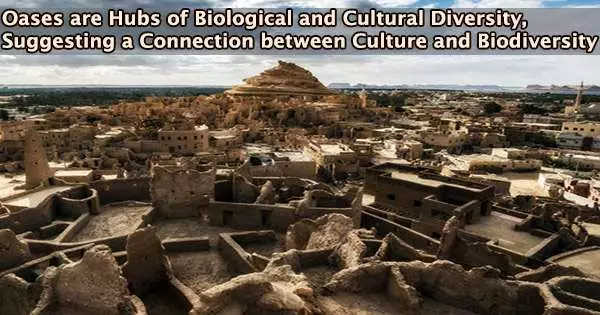

Oases in the Sahara Desert are lush, green pockets of vegetation and water surrounded by the arid desert landscape. These oases are essential for the survival of both plants and humans in the harsh desert environment.

A research team led by Prof. Dr. Klement Tockner, Director General of the Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung and Professor of Ecosystem Sciences at the Goethe University Frankfurt, has investigated the relationship between cultural and biological diversity for selected oases in the Sahara.

In their study, now published in the journal PLOS ONE, the researchers show that oases are centers of biocultural diversity, using Algeria as a concrete example. The researchers contend that as culture and biodiversity are particularly intertwined in these special desert ecosystems, both should be taken into account when developing strategies for their sustainable use and protection.

A quarter of the world’s languages, as well as a wide variety of nomadic cultures, can be found in arid regions. Deserts are home to a range of extremely well-adapted and unusual animals and plants, despite the fact that species richness in arid places is lower than in wet ecosystems like tropical forests.

At the same time, the distinct characteristics and isolation of various ecosystems make the diversity within species particularly noticeable. Oases green, fertile islands within desert areas play a central role in this.

“Foroases in the Sahara, the diversity of agriculturally used plant and animal species is particularly important,” explains the study’s corresponding author, Dr. Juan Antonio Hernández-Agüero, a former scientific assistant at the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt who now works at the VrijeUniversiteit Amsterdam.

“Date palm oases are a typical example. In addition to the economic importance of the fruits, they exhibit high genetic diversity and provide habitats and refuges for a variety of animals. Here, the close link between the evolution of human culture and biodiversity is particularly evident.”

The concept of biocultural diversity supports a holistic and interconnected view of nature and humans. Our study is intended as an impetus for a more profound analysis of the mechanisms of biocultural diversity in oases in order to develop the best possible sustainable use and protection concepts for these unique habitats.

Dr. Juan Antonio Hernández-Agüero

The scientists examined Algeria’s oases closely and examined the relationships between various elements of biological and cultural diversity, such as the number of animal and plant species and the number of ethnic groups and languages, in order to better understand the potential mechanisms of biocultural diversity in the Sahara.

“We studied 77 very different oases and 18 oasis groups. Collectively, the oases harbor 552 plant species, 14 amphibian species, 328 bird species, 98 mammal species, and 72 reptile species, although the diversity can be much higher. In addition, the Algerian oases are home to twelve ethnic populations, each speaking their own language, including five endangered languages,” says Hernández-Agüero.

“Thus, of the total of 22 languages found in Algeria a country with only moderate diversity from a global perspective over half are spoken in oases. Eight out of 10 endangered large vertebrate species in the Sahara-Sahel region find refugia here. Oases are obviously of immense importance for the biocultural diversity of the entire country. Moreover, at the level of individual oases, we found a strong correlation between the number of species and languages.”

The oases of the Sahara are changing as a result of globalization processes, industrialized agriculture, and tourism. Along with more conventional products like dates and olives, hotels and restaurants are now growing their own tomatoes and other crops. This is exacerbated by activities such as oil drilling and uranium mining.

“Over countless generations, traditional local cultivation practices have ensured the protection of biodiversity,” explains Prof. Dr. Klement Tockner. “It is therefore crucial to consider biological and cultural diversity together in order to sustainably use as well as protect oases in the Sahara and also globally in terms of their diversity and importance for humans. After all, around 450 million people in North Africa and Asia live in or near oases. Because of their natural resources, oases are among the most densely populated habitats in the world. And they are more severely threatened than ever before.”

“The concept of biocultural diversity supports a holistic and interconnected view of nature and humans,” adds Hernández-Agüero.

“Our study is intended as an impetus for a more profound analysis of the mechanisms of biocultural diversity in oases in order to develop the best possible sustainable use and protection concepts for these unique habitats,” he concludes.