In recent years we have seen major changes in the business world, including deregulation, the growing expectations of shareholders (the business owners) and the impact of new technology. These have led to a much more fast-changing and competitive environment that has radically altered the way in which businesses are managed.

This article discusses some of the management accounting methods that have been developed to help business maintain their competitiveness. Management accounting embraces both financial and non-financial measures. Financial measures have long been regarded as the most important measures for a business. They provide us with a valuable means of summarizing and evaluating business achievement, and there is no serious doubt about the continued importance of financial measures, in this role.

However, in recent years there has been increasing recognition that financial measures alone will not provide managers with the information that they require to manage business effectively. Non-financial measures should also be used to help gain a deeper understanding of the business and to achieve business objectives.

Financial measures portray aspects of business achievements (for example, sales, profits, return on capital employed and so on) that can help managers determine whether the business is increasing the wealth of its owners. This is vital in an increasingly competitive environment, but managers also need to understand what particular things drive the creation of wealth. These value drives, as they are often called, may be such things as employee satisfaction, customer loyalty and the level of product innovation. Often, they do not lend themselves to financial measurement. Non-financial measures, however, may be used to arrive at some indirect means of assessment.

- Employee satisfaction may be measure through the use of employee survey. This could be examine attitudes towards various aspects of the job, the degree of autonomy that is permitted, the level of recognition and reward received, the level of participation in decision making, the degree of support received in carrying out tasks and so on. Less direct measures of employee satisfaction may include employee turnover rates and employee productivity; however, other factors may have significant influence on these measures

- Customer loyalty may be measured through the proportion of total sales generated from existing customers, the number of repeated sales made by customers, the percentage of customers renewing subscriptions or other contracts and so on

- The level of product innovation may be measured through the number of innovations during a period compared with those of competitors, the percentage for sales attributable to recent product innovations, the number of innovations that are brought successfully to market and so on

Here is a very well known international business that focuses a lot of attention on non-financial measures:

- Pepsi-Cola attaches considerable importance to non-financial measures when assessing the success of the business. This is reflected in the fact that managers’ bonuses are linked to meeting targets based on non-financial measures, as well as more conventional financials measures. The non-financial measures included:

- Market-orientated measures, based on quality, customer attitudes and market share (known as marketplace profit and loss account); and

- Employee motivation, based on regular surveys

It has been argued that financial indicators are normally “lag” indicators, in that they tell us about outcomes. In other words, they measure the consequences arising from the management decisions that were made earlier. Non-financial measures can also be used as a “lag” indicator also, of course. They can, however, also be used as “lead” indicators by focusing on those things that drive the creation of wealth. It is argued that if we measure changes in these value drives, we may be able to predict changes in financial performance. For example, we may find from experience that if, during a particular period, there is a 10 per cent fall in the level of product innovation, this will lead to a 20 per cent fall in sales over the following three periods. In this case, the levels of product innovation can be regarded as a lead indicator that can alert managers to a future decline in sales unless corrective action is taken.

The Balanced Scorecard

One of the most impressive, and widely used, attempts to integrate the use of financial and non-financial measures has been the Balanced Scorecard[2]. The balanced scorecard is a strategic planning and management system that is used extensively in business and industry, government, and non-profit organizations worldwide to align business activities to the vision and strategy of the organization, improve internal and external communications, and monitor organization performance against strategic goals.

It was originated by Drs. Robert Kaplan (Harvard Business School) and David Norton as a performance measurement framework that added strategic non-financial performance measures to traditional financial metrics to give managers and executives a more ‘balanced’ view of organizational performance[3]. While the phrase balanced scorecard was coined in the early 1990s, the roots of the this type of approach are deep, and includes the pioneering work of General Electric on performance measurement reporting in the 1950’s and the work of French process engineers (who created the Tableau de Bord – literally, a “dashboard” of performance measures) in the early part of the 20th century.

The balanced scorecard has evolved from its early use as a simple performance measurement framework to a full strategic planning and management system. The “new” balanced scorecard transforms an organization’s strategic plan from an attractive but passive document into the “marching orders” for the organization on a daily basis. It provides a framework that not only provides performance measurements, but helps planners identify what should be done and measured. It enables executives to truly execute their strategies.

Kaplan and Norton describe the innovation of the balanced scorecard as follows:

“The balanced scorecard retains traditional financial measures. But financial measures tell the story of past events, an adequate story for industrial age companies for which investments in long-term capabilities and customer relationships were not critical for success. These financial measures are inadequate, however, for guiding and evaluating the journey that information age companies must make to create future value through investment in customers, suppliers, employees, processes, technology, and innovation.”

The Balanced Scorecard involves setting objectives and developing appropriate measures and targets in four main areas:

- Financial – This area will specify the financial returns required by shareholders and may involve the use of financial measures such as return on capital employed, net profit margin, percentage sales growth

- Customer – This area will specify the kind of customer and/or markets the business wishes to service and will establish appropriate measures such as customer satisfaction, new customer growth levels.

- Internal business process – This area will specify those business processes (for example, innovation, types of operations and after-sales service) that are important to the successes of the business. It will establish appropriate measures such as percentage of sales from new products, time to market for new products, product lifecycle tie and speed of response to customer complaints.

- Learning and growth – This area will specify the kind of people, the systems and the procedures that are necessary to deliver long-term business growth. This area is often the most difficult for the development of appropriate measures, however, examples of measures may include employee motivation, employee skills profiles and information systems capabilities.

The balanced scorecard does not prescribe the particular objectives, measures or targets that a business should adopt. This is a matter for the individual business to determine. It simply sets out the framework for developing a coherent set of objectives for the business and ensuring that they are then pursued in a systematic manner. This framework aims to strike a balance between the external measures relating to customers and shareholders, and the internal measures relating to internal business processes and learning growth. It also aims to strike a balance between the measures that portray outcomes (lag indicators) and measures that help predict future performances (lead indicators). Finally, the framework aims to strike a balance between “hard” financial measures and “soft” non-financial measures.

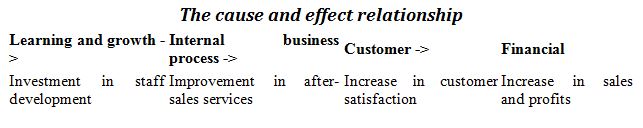

Although the Balanced Scorecard employs measures across a wide range of business activity, it does not seek to dilute the importance of financial measures and objectives. Kaplan and Norton emphasise the point that a Balanced Scorecard must reflect a concern for the financial objectives of the business and so measures and objectives in the other areas that have been identified must ultimately be related back to the financial objectives. There must be a clear cause and effect relationship. So, for example, an investment in staff development (in the learning and growth area) may lead to improved levels of after-sales service (internal business process area), which, in turn, may lead to higher levels of customer satisfaction (customer area) and, ultimately, higher sales revenue and profits (financial area)

Sir Terry Leahy, the chief executive of Tesco, speaking at the Leaders in London conference in London, October 2004, credited Professor Robert Kaplan, of Harvard Business School, with inspiring the explosion in growth at the supermarket chain. At the time, Tesco had revealed that half-year profits had surged 28 per cent to a record £805 million.[4]

“I have paid Robert Kaplan the only compliment he is interested in: putting his teaching into practice,” Sir Terry said. “He has had a big influence on Tesco.”

Sir Terry revealed that Tesco had implemented Professor Kaplan’s “Balanced Scorecard” approach to management through Tesco’s “Steering Wheel” system. The approach emphasises parts of a business that do not figure in conventional accounting. “The reason traditional business systems did a miserable job in helping companies to grow is because they ignore so called ‘intangibles’, such as customer relationships,” Professor Kaplan said at the same conference. The approach was meant to be an antidote to a culture “where everything is about selling more and spending less and anything else is background music,” he added.

Tesco’s version of the plan divides the business into four sections. Managers are asked to monitor customers, operations, staff and finances using a “traffic light” system where green indicates that targets are being met and red flags a problem. Sir Terry said that the method had been integral in differentiating the “two Tescos” – the unfashionable chain of the early 1990s, which held the No3 spot in Britain and operated only in the UK, and the modern day company, which leads the UK market and ranks No3 in the world.

“This system literally steers our business and our people,” Sir Terry said, adding that he was deeply suspicious of “management gobbledygook”.

It is important to recognise that the balanced scorecard by definition is not a complex thing – typically no more than about 20 measures spread across a mix of financial and non-financial topics, and easily reported manually (on paper, or using simple Office software).

The processes of collecting, reporting, and distributing balanced scorecard information can be labor intensive and prone to procedural problems (for example, getting all relevant people to return the information required by the required date). The simplest mechanism to use is to delegate these activities to an individual, and many balanced scorecards are reported via ad-hoc methods based around email, phone calls and office software.

In more complex organizations, where there are multiple balanced scorecards to report and/or a need for co-ordination of results between balanced scorecards (for example, if one level of balanced scorecard reports relies on information collected and reported at a lower level) the use of individual balanced scorecard reporters is problematic. Where these conditions apply, organisations use balanced scorecard reporting software to automate the production and distribution of these reports.

A recent survey[5], found that roughly 1/3 of organizations use office software to report their Balanced Scorecard, 1/3 use bespoke software developed specifically for their own use, and 1/3 use one of the many commercial packages available.

There are currently over 100 vendors of software suitable for Balanced Scorecard reporting (i.e. supporting data collection, reporting and analysis)

Growing Importance of Non-financial Performance Measures

Studies of price changes showed that in a well managed competitive economy, sustained cost reduction was achieved by firms over a long period as experience was accumulated. Thus those who have high market share should achieve the greatest returns, because this allowed them to accumulate experience. If true, this created a significant tension for management, because profit – as conventionally measured under normal accounting rules – could always be increased in the short term by selling off market share. Unless constraints were placed on management to require maintaining market share, and only profitability was emphasised, the long term health of the company could be sacrificed (Davis J. ‘Conceptual Issues in Strategic Management’, in New Developments in Public Sector Management: Strategic Planning and Review of Government Operations, ANU 1982)

Today’s management accounting information is inappropriate for manager’s planning and control. Many short term measures are appropriate for motivating and evaluating performance, but profitability based on requirements for external observers is not one of them. Bookkeeping has a long history, but was not expected to provide a form of management information until the 19th century. Many simple management accounting measures served the needs of both managers and owners. Others evolved to measure process performance, but not profit – though when firms had only one function – efficient performance of that task usually meant profitability. The development of conglomerate enterprises in the early 20th century required means for assessing performance of different divisions. Return on investment was developed. This has remained standard, though after the 1960s the competitive environment changed and this measure ceased to be the most relevant guide to future performance. US firms lost competitiveness because their actions were guided by ROI considerations which were inappropriate ways of assessing performance in the new environment (Johnson T. And Kaplan R., Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting, Harvard Business School Press, 1987)

There is a shift from treating financial measures as the foundation for performance measures, to being only one of several measures. Firms found that financial measures undercut strategy – and devised new measures where financial considerations were less significant. Need to know what measures truly predict long term success. It is now being shown that accrual accounting systems are obsolete – and often harmful. This relates to concern about short term focus of firms, which affects their competitiveness. Long term strategies were not done because of short term financial effects. Also staff play games to maximize financial measures so making them meaningless. Financial figures assess results of past decisions, but do not cover crucial factors for future performance (eg quality / customer satisfaction – which have different criteria). Benchmarking also makes people aware of large scope for improvement which may exist. Many companies described strategy in terms of customer service, innovation etc – but did not measure it. A coherent organization wide grammar is vital to measurements which are viable in rapidly changing structures. Such change is vital to competitive performance. Methods for measuring financial data are most sophisticated. Putting non-financial measures on an equal footing will be a major task. Incentives need to be aligned with performance measurements, but not through a formula – which is either too simple or too complex – judgment must be used (Eccles R. ‘The Performance Measurement Manifesto’, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb 1991)

Companies worldwide are transforming themselves for a world where competition is based more on information, and on ability to exploit intangible assets, than on their ability to invest in, and manage, tangible assets. Concept of balanced scorecard was introduced to complement financial measures with those related to: customers; internal business processes; and learning. Some have used this as cornerstone of a new strategic management system. Most organizations’ operational and management control systems are built around financial measures and targets which have nothing to do with strategy – but balanced scorecard allows processes which create link. Most organizations separate strategy formulation and financial budgeting, with most emphasis on the latter. Balanced scorecard allows these processes to be integrated – identifies strategic objectives, and critical drivers, and allows organizations various change programs to be managed. In turbulent environment, strategy must be constantly redeveloped. Budget and financial measures do not allow this – but strategic learning is possible. (Kaplan R. and Norton D., ‘Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System’, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb 1996)

Performance review can shed light on the real drivers of organizational value, and everyone must now redesign their approach to performance measurement. A balanced family of performance measures is required – which provide comprehensive view of whole organization, and are individually meaningful. Key is to discover how human, organizational and intellectual assets combine to create value. Measurement is more useful in defining goals than assessing performance – because measurement only refers to a model, not to the real situation. Measures should be closely aligned with current organizational strategies and objectives. Performance measures are used to: measure progress towards goals; calibrate conformance to policies; appraise individual performance; and assess performance of systems and procedures. Measures should be robust, simple, reliable; arise naturally from operations; be limited to controllable factors; hierarchical; and cover an appropriate period. For good results need: balanced set of measures, and ability to influence behavior.