Non-alcoholic beverages are rich in nutrients and bioactive compounds that have the potential to influence human health and increase or decrease the risk of chronic diseases. A wide range of beverage constituents are absorbed in the gut, circulated in the bloodstream, and excreted in urine. They could be used as compliance markers in intervention studies or as biomarkers of intake to improve beverage consumption measurements in cohort studies and uncover new associations with disease outcomes that were previously missed when using dietary questionnaires.

In search of new biomarkers for nutrition and health studies, a research team from the Leibniz Institute for Food Systems Biology at the Technical University of Munich (LSB) identified and structurally characterized three metabolites that could be considered specific markers for individual coffee consumption. These are degradation products of a class of substances that are produced in large quantities during coffee roasting but are rarely found in other foods. This, along with the fact that the potential biomarkers can be detected in very small amounts of urine, makes them appealing for future human studies.

Coffee is by far the most popular hot beverage in Germany, according to Statista. On average, each person consumes 168 liters of water per year. It is not only a stimulant, but it also has health benefits. Numerous observational studies, for example, show that moderate coffee consumption is associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes or liver disease.

Our findings help advance biomarker research. Food-specific biomarkers are important tools to explore the health effects of food. Therefore, part of our scientific work at LSB is also focused on finding biomarkers for food consumption.”

Roman Lang

Biomarkers rather than self-reporting

However, in terms of coffee consumption, such observational studies rely on participants’ self-reports, which are difficult to verify. “Complementary studies in which coffee consumption could be objectively verified using biomarkers would thus be desirable in order to determine the health value of coffee even more reliably,” says Roman Lang, head of the LSB’s Biosystems Chemistry & Human Metabolism research group.

Although earlier studies had already pointed to biomarker candidates, research on this had stalled for years. The substances previously detected were metabolic intermediates or breakdown products (metabolites) of various coffee compounds whose urine concentrations correlated strongly with the level of coffee consumption. At the time, however, the researchers had not succeeded in clearly identifying the molecular structure of the metabolites.

Use of high-performance analytical technologies

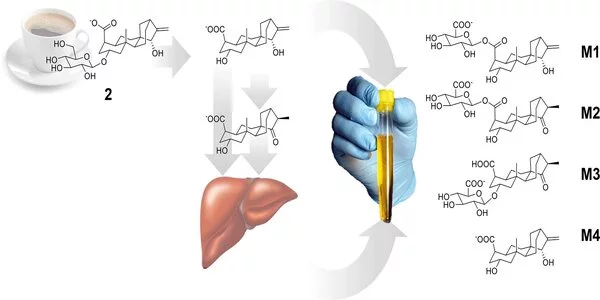

Therefore, as part of a pilot study, Roman Lang’s team examined the urine samples of six people after they had consumed 400 ml of coffee three hours earlier. With the help of high-performance analytical technologies and self-produced reference substances, the team succeeded in identifying three candidate biomarkers in the urine and, for the first time, in clearly determining their chemical structure. These are a glucuronic acid conjugate of atractyligenin, whose glycosides are present in relatively high concentrations in coffee beverages, and two glucuronic acid derivatives of an atractyligenin oxidation product.

“Our findings help advance biomarker research,” says Roman Lang. Dose-response studies, pharmacokinetics and human studies with much larger numbers of subjects must now follow to test the biomarker suitability of the identified compounds, he adds. Veronika Somoza, director of the Freising-based Leibniz Institute adds, “Food-specific biomarkers are important tools to explore the health effects of food. Therefore, part of our scientific work at LSB is also focused on finding biomarkers for food consumption.”

Function of glucuronic acid conjugates

In human metabolism, glucuronic acid serves in particular the so-called “detoxification” of nonpolar substances. The latter include, for example, ingested drugs or plant substances, but also endogenous steroid hormones. The body converts the substances to glucuronides in the liver by binding them to glucuronic acid. These glucuronic acid conjugates are much more water-soluble than the original substances and can thus be easily excreted in the urine via the kidneys.