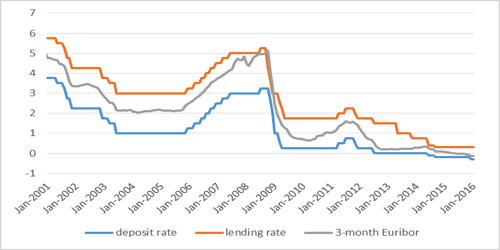

Negative interest rates occur when borrowers are credited interest rather than paying interest to lenders. Under a negative rate policy, financial institutions are required to pay interest for parking excess reserves with the central bank. Negative interest on excess reserves is an instrument of the unconventional monetary policy applied by central banks to encourage lending by making it costly for commercial banks to hold their excess reserves at central banks so they will lend more readily to the private sector. A negative interest rate policy brings the rate of interest paid on excess reserves below zero. Such a policy is usually a response to very slow economic growth, deflation, and deleveraging. Negative interest rates might be seen during deflationary periods when people or institutions are inclined to hoard money, rather than spend or lend it. That way, central banks penalize financial institutions for holding on to cash in the hope of prompting them to boost lending to businesses and consumers.

During economic downturns, central banks often lower interest rates to stimulate growth. With negative interest rates, banks charge you interest to keep cash with them, rather than paying you interest. Negative monetary policy rates are associated with particular friction because the remuneration of retail deposits tends to be floored at zero. Until late in the 20th century, it was thought that rates could not go below zero because banks would hold onto cash instead of paying a fee to deposit it. It turns out this was not quite right. Market interest rates are not a policy; rather they are influenced by various monetary policy choices, perhaps over a long period of time. Central banks in Europe and in Japan have demonstrated rates can go negative, and several have pushed them in that direction for the same reason they lowered them to zero in the first place—to provide stimulus and, where inflation is below target, to raise the inflation rate. While such a policy is widely considered valid only for economies in Europe and Japan with chronically low inflation and weak growth, the idea is attracting other supporters elsewhere – not least U.S. The notion is that negative rates will provide even more incentive for commercial banks to make loans. Aside from lowering borrowing costs, advocates of negative rates say they help weaken a country’s currency by making it a less attractive investment than other currencies.

The negative interest rate is meant to be an incentive for banks to make loans during a period in which they would rather hang on to funds. What might have looked like a potential lending project, by a bank, not worth funding even in a low-interest-rate environment might now look attractive if the alternative is being charged to store money at the central bank or holding a large amount of cash. But negative rates also narrow the margin that financial institutions earn from lending. If prolonged ultra-low rates hurt the health of financial institutions too much, they could stop lending and damage the economy.