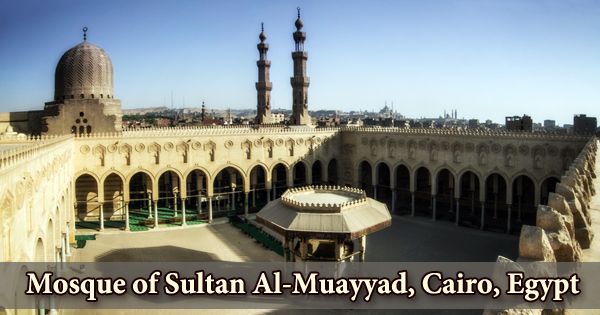

The Mosque of Sultan al-Mu’ayyad (Arabic: مسجد السلطان المؤيد) was built on the site of an old jail where the Mamluk sultan Al-Mu’ayyad Sayf Aldin Shaykh was imprisoned when he was a Mamluk soldier. It is a mosque located near to Bab Zuwayla in Cairo, Egypt; its construction began in 1415 and was completed in 1421. It is regarded as one of Egypt’s most remarkable specimens of Mamluk architecture, and the mosque and its minarets have become a landmark of Cairo due to its location. A Friday Mosque and a madrasa for four madhhabs were part of the compound. It took the site of a prison that had stood near to Bab Zuwayla.

From 1412 to 1421, Al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh, a Burji or Circassian Mamluk, was Sultan. According to al-Maqrizi, al-Mu’ayyad, a famous intriguer during a time of tremendous intrigues, was kidnapped and imprisoned on this spot during the reign of Faraj ibn Barquq. He was horribly afflicted by lice and fleas, and pledged at the time that if he ever gained power, he would turn the filthy prison into a “holy location for the teaching of academics.” It was built at a cost of forty thousand dinars by Sultan al-Mu’ayyad.

There were four front faces and a few entrances on the construction. The main gateway of the mosque is elegantly embellished with muqarnas and kufic calligraphic lettering. The madrasa became one of the most important scholastic institutions of the fifteenth century as a result of the sultan’s rich endowments. A substantial library was gathered, professorial positions were filled with the most distinguished scholars of the day, and Egypt’s most famous Quaranic exegete, Ibn Hajar al-‘Asqalani, was appointed as a lecturer in Shafi’i jurisprudence.

Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh died eleven years after assuming power in 1421. He had a reputation as a humble guy and one of Cairo’s major patrons of architecture throughout his reign. Several religious and secular constructions, including a khanqah at Giza, palaces along the Khalij el-Arab and the Nile, and the Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Mosque, were left behind when the sultan died. Sultan al Muayyad was imprisoned in the same site as the Mosque, where he was tortured and suffered greatly as a result, and he promised to turn the prison into a mosque and madrasa if he rose to power after his freedom was restored.

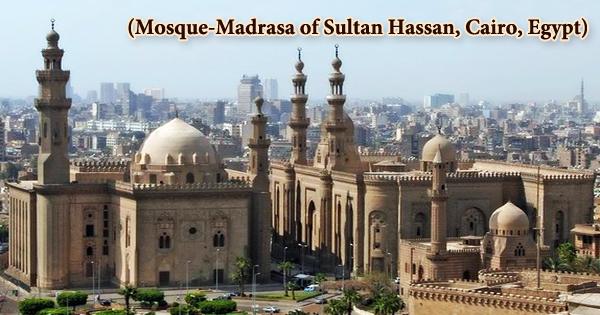

Because the mosque required so much marble, part of it was sourced from pre-existing structures. Many other features of the mosque, including the mosque’s columns and a stunning bronze entrance and chandelier, were cannibalized from other buildings. The door and chandelier in particular are well-known examples; both are thought to have come from Sultan Hassan’s Mosque-Madrassa. Unlike Barquq’s madrasa-khanqah, where khanqah Sufis and madrasa students shared a home and were exposed to each other’s teachings and religious practices, this madrasa was solely for Sufis. Its curriculum included the study of official religion according to the four rites.

The mosque’s twin minarets, positioned above Bab Zawila, give a unique photo opportunity because both are open to climb. The mausoleum of the Al Muayyad family may be found inside the mosque, inside a gorgeous marble tomb that was imported from various sites. Taking the door and chandelier from the old mosque was unlawful while the Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Mosque was being built, therefore taking them was comparable to robbery, despite the Sultan’s donations to the previous mosque. Although the new mosque was not formally completed until 1422, it was celebrated with an initial party in November 1419.

Sultan Al Muayyad made a commitment to himself that if he came to power, he would turn the prison where he was imprisoned into a magnificent institution for study. The last magnificent hypostyle mosque to be erected in Cairo was this one. A bending entryway and a burial chamber capped with a colossal dome, two Mamluk architectural characteristics, are among the features included into the hypostyle concept. The muqarnas entrance is framed by a pishtaq, or rectangular frame, which rises over the facade’s wall. The door, which is said to have been illegally taken from Sultan Hasan’s Madrasa, is a Mamluk metalwork masterpiece.

According to al-account Maqrizi’s of its origins, the mosque was built as a burial complex and for Friday prayers, but its primary use was as a madrasa for Sufi students. The mosque’s builder, Muhammad ibn al-Qazzaz, took use of the mosque’s proximity to Bab Zuwayla by employing its towers as buttresses and bases for the two identical minarets. The carved chevrons on the exterior of the stone dome, which can also be seen on the twin minarets’ octagonal second levels, are an exceptional example of this sort of surface ornamentation for carved masonry domes from this period.

Sultan Al Muyaddah spent a lot of money on the mosque and madrasa structures, which he funded with taxes and other donations from other mosques. One of the most well-known portions of his mosque was originally from the Sultan Hassan Mosque. The mosque was originally supposed to include a symmetrical pair of domed mausoleums flanking a prayer hall, but this ambition was stifled when the second mausoleum’s dome was not completed. Funerary apartments on both sides of the prayer hall house the Sultan and his son in one and female members of the Sultan’s family in the other.

From the mausoleum, one enters the congregational mosque’s sanctuary, which is a late example of the open courtyard plan on a vast scale in Cairo. The mosque had four facades initially, but it was in such bad shape in the late 1800s that the Comite reconstructed the western front and turned the courtyard into a garden. The Sultan’s chamber has a domed ceiling, as intended, but the women’s chamber has a flat ceiling. This dome is a scaled-down version of Faraj’s twin domes; the dome appears excessively small in comparison to the mosque’s size.

The Mu’ayyad Mosque is remains one of Cairo’s most magnificent mosques today, a testament to Sultan Mu’ayyad’s reputation as a renowned patron of the arts. Both the mihrab and the minbar are adorned in a historic style. The minbar is adorned with intricately carved wooden doors and panels, as well as a massive polychrome marble rosette above it. This is particularly unusual because this style is more commonly found on the floor than on the wall.

A hammam (bath) is located on the courtyard’s western side and is worth seeing. The sanctuary’s decoration is also of a quality and scale that is rarely seen later in the Mamluk period. The mihrab and minbar are both excellent specimens of the period’s style, while the ceilings, which were rebuilt in the early twentieth century, have the appearance of suspended carpets. In comparison to other mosques in the neighborhood, the mosque has a huge pavilion with an ablutions fountain in the center.

The original fountain was supposed to have marble columns with a gilded wooden dome above an awning, adding to the opulence of the structure. The ruins of a hammam, which was part of the mosque’s foundation, may be discovered just west of the mosque. The view from the top is well worth the climb because it provides a fantastic perspective of the mediaval city’s expanse and curves to the north and south. Carved cartouches signed and dated by the architect upon completion of each minaret may be found inside.

The inaugural event was memorable because it was attended by Sultan al-Mu’ayyad and his Mamluk entourage, and the water basin in the center of the enormous courtyard was filled with liquefied sugar, and sweets were offered. The mosque was restored once more in 2001, this time on the orders of Egypt’s Ministry of Culture. The renovations also include the reconstruction of the courtyard’s lost arches. The southern wall of al-Qahira has also been discovered. It’s on exhibit on the courtyard’s south side.

Information Sources: