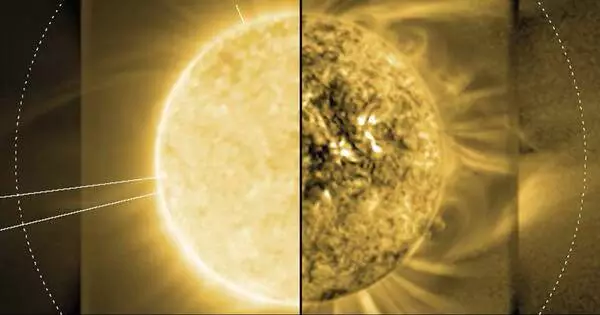

A star’s corona is the outermost layer of its atmosphere. It is made of plasma. The Sun’s corona extends millions of kilometers into space above the chromosphere. It is best seen during a total solar eclipse, but it can also be seen with a coronagraph. Spectroscopic measurements show that the corona is heavily ionized and that the plasma temperature exceeds 1000000 kelvins, making it much hotter than the Sun’s surface, known as the photosphere.

Web-like plasma structures have been discovered in the Sun’s middle corona by researchers. The researchers describe their novel new observation method, which involves imaging the middle corona in ultraviolet (UV) wavelength. The findings could help scientists better understand the origins of solar wind and how it interacts with the rest of the solar system.

Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), NASA, and the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research collaborated to discover web-like plasma structures in the Sun’s middle corona. In a new study published in Nature Astronomy, the researchers describe their innovative new observation method for imaging the middle corona in ultraviolet wavelength. The findings could help scientists better understand the origins of solar wind and how it interacts with the rest of the solar system.

We’ve known since the 1950s about the outflow of the solar wind. As the solar wind evolves, it can drive space weather and affect things like power grids, satellites, and astronauts.

Dr. Dan Seaton

Since 1995, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has observed the Sun’s corona with the Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) stationed aboard the NASA and European Space Agency Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft to monitor space weather that could affect the Earth. But LASCO has a gap in observations that obscures our view of the middle solar corona, where the solar wind originates.

“We’ve known since the 1950s about the outflow of the solar wind. As the solar wind evolves, it can drive space weather and affect things like power grids, satellites, and astronauts,” said SwRI Principal Scientist Dr. Dan Seaton, one of the authors of the study. “The origins of the solar wind itself and its structure remain somewhat mysterious. While we have a basic understanding of processes, we haven’t had observations like these before, so we had to work with a gap in information.”

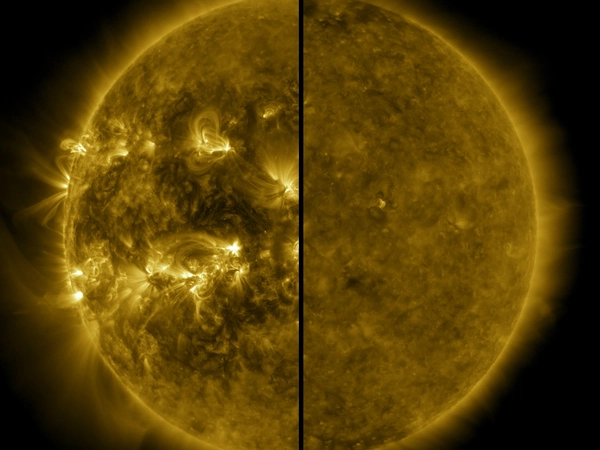

To find new ways to observe the Sun’s corona, Seaton suggested pointing a different instrument, the Solar Ultraviolet Imager (SUVI) on NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES), at either side of the Sun instead of directly at it and making UV observations for a month. What Seaton and his colleagues saw were elongated, web-like plasma structures in the Sun’s middle corona. Interactions within these structures release stored magnetic energy propelling particles into space.

“No one had monitored what the Sun’s corona was doing in UV at this height for that amount of time. We had no idea if it would work or what we would see,” he said. “The results were very exciting. For the first time, we have high-quality observations that completely unite our observations of the Sun and the heliosphere as a single system.”

Seaton believes these observations could lead to more comprehensive insights and even more exciting discoveries from missions like PUNCH (Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere), an SwRI-led NASA mission that will image how the Sun’s outer corona becomes the solar wind.

“Now that we can image the Sun’s middle corona, we can connect what PUNCH sees back to its origins and have a more complete view of how the solar wind interacts with the rest of the solar system,” Seaton said. “Prior to these observations, very few people believed you could observe the middle corona to these distances in UV. These studies have opened up a whole new approach to observing the corona on a large scale.”

The First Ultraviolet Imaging Of The Sun’s Middle Corona https://t.co/n5c9KBpgl6 #heliophysics #spaceweather pic.twitter.com/dwSxZ2XlUH

— SpaceRef (@SpaceRef) December 13, 2022