According to new research from the University of Colorado Boulder published in JAMA Pediatrics, nearly one in every five school-aged children and preteens now take melatonin for sleep, and some parents routinely give the hormone to preschoolers. This worries the authors, who point out that there is little data on the products’ safety and efficacy, and that such dietary supplements are not fully regulated by the Food and Drug Administration.

“We hope this paper raises awareness for parents and clinicians while also raising the alarm for the scientific community,” said lead author Lauren Hartstein, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in CU Boulder’s Sleep and Development Lab. “We are not claiming that melatonin is always harmful to children. However, much more research is required before we can confidently state that it is safe for children to take long-term.”

We hope this paper raises awareness for parents and clinicians while also raising the alarm for the scientific community. We are not claiming that melatonin is always harmful to children. However, much more research is required before we can confidently state that it is safe for children to take long-term.

Lauren Hartstein

Calls to poison control centers up

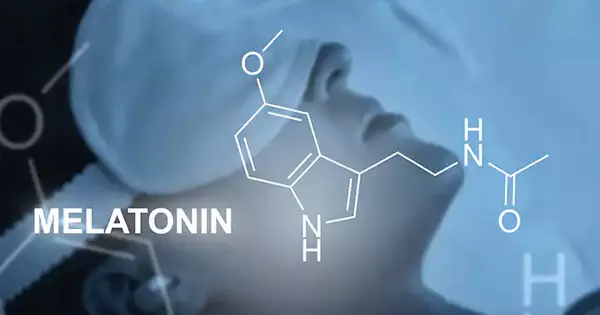

Melatonin is naturally produced in the pineal gland to signal the body that it is time to sleep and to regulate its circadian rhythm (the 24-hour physiological cycle). The hormone is classified as a drug in many countries and is only available with a prescription.

In the United States, however, chemically synthesized or animal-derived melatonin is available as a dietary supplement over the counter, and it is increasingly available in child-friendly gummies.

“All of a sudden, in 2022, we started noticing a lot of parents telling us that their healthy child was regularly taking melatonin,” said Hartstein, who researches how environmental cues, such as light at night, influence children’s sleep quality and melatonin production.

During 2017-18, only about 1.3% of U.S. parents reported that their children used melatonin. To get a sense of the current prevalence of use, Hartstein and colleagues surveyed about 1,000 parents in the first half of 2023.

Among children ages 5 to 9, 18.5% surveyed had been given melatonin in the previous 30 days. For preteens ages 10 to 13, that number rose to 19.4%. Nearly 6% of preschoolers ages 1 to 4 had used melatonin in the previous month.

Preschoolers who used melatonin had been taking it for a median length of a year. Grade-schoolers and preteens had used it for median lengths of 18 and 21 months, respectively. The older the child, the greater the dosage, with preschoolers taking anywhere from 0.25 to 2 mg and preteens taking up to 10 mg.

A need for caution

In a study published in April, researchers analyzed 25 melatonin gummy products and found that 22 contained different amounts of melatonin than the label indicated. One had more than three times the amount on the label. One had none at all. In addition, some melatonin supplements have been found to contain other concerning substances, such as serotonin.

“Parents may not actually know what they are giving to their children when administering these supplements,” Hartstein said. Some scientists are also concerned that giving melatonin to children whose brains and bodies are still developing may affect the timing of puberty.

The few small-scale human studies that have investigated this have produced inconclusive results. Gummies, in particular, pose an additional risk because they resemble and taste like candy. The authors note that between 2012 and 2021, reports of melatonin ingestion to poison control centers increased 530%, with the majority of cases occurring in children under the age of five. More than 94% of the incidents were unintentional, and 85% were asymptomatic.

A place for judicious use

Co-author Julie Boergers, Ph.D., a psychologist and pediatric sleep specialist at Rhode Island Hospital and the Alpert Medical School of Brown University, said that when used under the supervision of a health care provider, melatonin can be a useful short-term aid, particularly in youth with autism or severe sleep problems.

“But it is almost never a first-line treatment,” she said, noting that she often recommends that families look to behavioral changes first and use melatonin only temporarily. “Although it’s typically well-tolerated, whenever we’re using any kind of medication or supplement in a young, developing body we want to exercise caution.”

Anecdotally, she has heard from parents that the supplement often works well at first, but that children may require higher doses over time to achieve the same effect. According to Hartstein, introducing melatonin early in life may have another unintended consequence: It could imply that if you have trouble sleeping, a pill is the solution.

The authors emphasize that the study was small and does not necessarily represent usage across the country. Nonetheless, it is telling.

“If this many kids are taking melatonin, that suggests there are a lot of underlying sleep issues out there that need to be addressed,” said Hartstein. “Addressing the symptom doesn’t necessarily address the cause.”