Scientists discovered that modern ocean biodiversity, which is at its highest level ever, was attained by long-term stability of the position of so-called biodiversity hotspots, locations with a very high number of species. The discoveries, reported in Nature, were made possible by a ground-breaking model that reconstructs the diversity of marine organisms from their origin 550 million years ago to the present, using plate tectonics and climatic factors such as ocean temperature and food supply.

The new model, unlike the fossil record, is free of gaps and sampling biases since the model’s history of variety is numerically simulated rather than reconstructed from fossil data. The model demonstrates that the increase in diversity is true and is linked to the formation of variety hotspots over the last 200 million years, when the Earth’s climatic circumstances were largely stable.

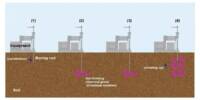

The research team employed a palaeogeographic model to monitor the motions of continents and the seafloor across geological time, as well as a paleo-Earth system model to reconstruct the environmental conditions of ancient oceans, to prepare the work. In the model, each tracked region accumulates diversity over time at a rate controlled by the environmental conditions of each region and at each time.

Our approach resolves some of the previous debates about whether the record of fossils in the rocks is good enough to provide a clear pattern of biodiversity change through deep time.

Prof Michael Benton

“Our approach resolves some of the previous debates about whether the record of fossils in the rocks is good enough to provide a clear pattern of biodiversity change through deep time,” explained co-author Prof Michael Benton of the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences.

Until now, understanding of the global-scale history of biodiversity and the origins of modern biodiversity has been based on the fossil record, which shows that life on our planet has been subjected to at least five catastrophic extinctions during the last half billion years. The Permian-Triassic mass extinction, the biggest of all time, wiped out more than 90 percent of marine species, threatening ecosystems. Life in the oceans is more diversified than ever today, 250 million years later.

“The question is how did we get to where we are,” said the ICM-CSIC researcher and project leader Pedro Cermeño. “Gaps in the fossil record require the use of a new computational approach to reconstruct the history of life. Our model is able to recreate the geographic distribution of modern ocean diversity, especially the hotspots, and reveals the mechanisms that have created them.”

For the past fifty years, palaeontologists have argued about the quality of the fossil record. “We were not sure whether it is good enough to give a reasonable picture of past diversity and details of how life recovered after mass extinctions,” said Prof Benton.

Carmen Garca-Comas, an ICM-CSIC researcher who led the study, added: “It was thrilling to see that the dynamics of global diversity emerging from our regional diversification model were similar to those observed in the fossil record. This lends credence to the model’s application in reconstructing the geographic distributions of diversity over time, allowing us to determine when and how marine biodiversity hotspots emerged.”

The new model also sheds insight on one of the most contentious issues in evolutionary ecology: whether or not the Earth’s diversity has a limit. According to ecological theory, as diversity increases and biological interactions, such as competition, become more intense, the process of diversification grinds to a standstill, and the appearance and establishment of a new species will inevitably result in the extinction of an old one.

However, some scientists claim that because Earth’s ecosystems are so diverse, there will always be room for more species. Our findings harmonize both points of view. While the majority of the seas have levels of diversity much below their maximum, places holding diversity hotspots may be near to their limit.

“This modelling tool is really powerful as it allows us to explore a lot of things, including what would have happened if some of the big mass extinctions had never happened or if they had happened at another time in Earth’s history,” stated Mr. Cermeño.

Human meddling in the natural functioning of Earth systems has caused the sixth great mass extinction, according to researchers. According to the United Nations, as many species have vanished in the last century as would be extinct in 10,000 years given a typical, non-extinction situation. Furthermore, 25% of the species assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature are currently threatened with extinction.

“Our study underscores that, if current trends continue, projected diversity loss might take millions of years to recover, arguably beyond the lifespan of our species,” Prof Benton said.