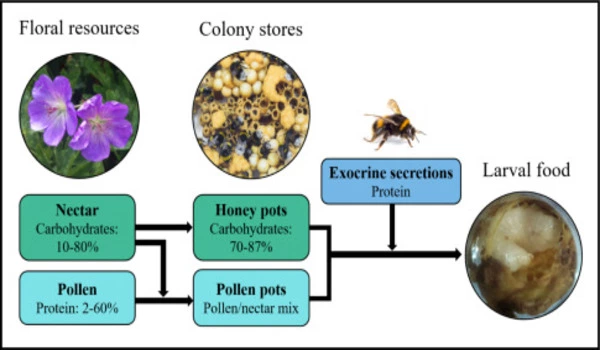

There are certain elements in bumble bee diets that can be considered the “bee’s knees” or the best choices for their nutrition. Like other bees, bumble bees primarily feed on nectar and pollen. Their dietary preferences, however, can vary depending on the species and the availability of food sources in their environment.

A new study has identified the best dietary options for bumble bees in Ohio and the Upper Midwest. Over the course of two years, researchers observed nearly 23,000 bumble bee-flower interactions and discovered that these bees do not always choose the most abundant flowers in their foraging area, implying that they have more discerning dietary preferences than one might expect.

Bumble bees are important pollinators because they are large, strong, and social bees that can fly long distances. However, like other pollinators threatened by habitat loss, climate change, and disease, the numbers of some species are dwindling.

According to the researchers, this new data can help guide planting decisions for both professional and amateur conservationists.

Getting over 20,000 observations of individual identified bumble bees visiting particular flower species is pretty incredible for a dataset. Having flower associations as well as estimates of flower abundance was critical for this project, so we counted the flowers as well.

Karen Goodell

“Getting over 20,000 observations of an individual identified bumble bees visiting particular flower species is pretty incredible for a dataset,” said Karen Goodell, senior author of the study and professor of evolution, ecology, and organismal biology at Ohio State University’s Newark campus. “Having flower associations as well as estimates of flower abundance was critical for this project, so we counted the flowers as well.”

The top flower species preferred by an aggregate of bumble bee species in Ohio are milkweed, native thistles, morning glory, purple coneflower, bee balm, beardtongue, red clover, vetch, and rosinweed, or cup plant. Culver’s root and wild indigo were two other “bee magnet” plants that were crawling with the fuzzy buzzers.

The study was published recently in the journal Ecosphere.

Researchers observed only 10 of the 16 bumble bee species previously found in Ohio, eight of which were abundant enough to include in the analysis – including the American Bumble Bee (Bombus pensylvanicus), which is under consideration for inclusion on the Federal Endangered Species List. The Common Eastern Bumble Bee (Bombus impatiens) was the most frequently observed species, with 11,555 visits total, compared to only 31 observations of the American Bumble Bee.

In fact, despite the extensive sampling, the authors are confident in the range of preferred flowers for only the three most common species. For the five less common species, researchers didn’t witness enough bee-flower interactions to fully account for what they eat. That sparseness of data on the rarer species speaks to the need for this comprehensive analysis, researchers said.

“It’s really important to know what species we do have and what they like to eat, because any of them could become rare,” Goodell said. “It’s not like we’re doing a fantastic job of taking care of our natural areas. The more information we have about their preferences, the better we can manage their habitat.”

During the summer months of 2017 and 2018, the research team visited 228 locations in Ohio for a total of 477 hours and observed bumble bees interacting with 96 different species of wildflowers. Unmanaged fields, restored roadsides and meadows, and planted urban patches and hayfields were among the sites.

The data analysis revealed strong nonrandom patterns of bumble bee visits to flowers, implying that the bees chose specific plants in greater proportion than their availability would imply. The researchers used a selection index to determine bees’ flower preferences, which compared the frequency of bumble bee species visits to the overall percent abundance of the flowers.

“What we were trying to get at was, if everything else is equal, what do they actually prefer?” said first author Jessie Lanterman Novotny, an Ohio State PhD student and postdoctoral researcher in Goodell’s lab who led much of the project. “There were less abundant flowers that bees actively sought out; they didn’t always eat what was most abundant.” They also avoided certain plants: no matter how many of a certain flower there were, they said, ‘No thanks.'”

The researchers identified a few plants, including alsike clover, black-eyed Susan, and prairie cone flower, that are abundant and commonly used in pollinator conservation plantings and seed mixes but that bumble bees consistently ignore. Five of the eight bumble bee species also were strongly drawn to non-native plants, which poses a dilemma for conservation planters focused on preserving native plant species.