An Overview of Inflation

Measures:

Inflation is usually estimated by calculating the inflation rate of a price index, usually the Consumer Price Index.[24] The Consumer Price Index measures prices of a selection of goods and services purchased by a “typical consumer”.[25] The inflation rate is the percentage rate of change of a price index over time.

For instance, in January 2007, the U.S. Consumer Price Index was 202.416, and in January 2008 it was 211.080. The formula for calculating the annual percentage rate inflation in the CPI over the course of 2007 is

The resulting inflation rate for the CPI in this one year period is 4.28%, meaning the general level of prices for typical U.S. consumers rose by approximately four percent in 2007.[26]

Other widely used price indices for calculating price inflation include the following:

Producer price indices (PPIs) which measures average changes in prices received by domestic producers for their output. This differs from the CPI in that price subsidization, profits, and taxes may cause the amount received by the producer to differ from what the consumer paid. There is also typically a delay between an increase in the PPI and any eventual increase in the CPI. Producer price index measures the pressure being put on producers by the costs of their raw materials. This could be “passed on” to consumers, or it could be absorbed by profits, or offset by increasing productivity. In India and the United States, an earlier version of the PPI was called the Wholesale Price Index.

Commodity price indices, which measure the price of a selection of commodities. In the present commodity price indices are weighted by the relative importance of the components to the “all in” cost of an employee.

Core price indices: because food and oil prices can change quickly due to changes in supply and demand conditions in the food and oil markets, it can be difficult to detect the long run trend in price levels when those prices are included. Therefore most statistical agencies also report a measure of ‘core inflation’, which removes the most volatile components (such as food and oil) from a broad price index like the CPI. Because core inflation is less affected by short run supply and demand conditions in specific markets, central banks rely on it to better measure the inflationary impact of current monetary policy.

Other common measures of inflation are:

GDP deflator is a measure of the price of all the goods and services included in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The US Commerce Department publishes a deflator series for US GDP, defined as its nominal GDP measure divided by its real GDP measure.

Regional inflation The Bureau of Labor Statistics breaks down CPI-U calculations down to different regions of the US.

Historical inflation before collecting consistent econometric data became standard for governments, and for the purpose of comparing absolute, rather than relative standards of living, various economists have calculated imputed inflation figures. Most inflation data before the early 20th century is imputed based on the known costs of goods, rather than compiled at the time. It is also used to adjust for the differences in real standard of living for the presence of technology.

Asset price inflation is an undue increase in the prices of real or financial assets, such as stock (equity) and real estate. While there is no widely accepted index of this type, some central bankers have suggested that it would be better to aim at stabilizing a wider general price level inflation measure that includes some asset prices, instead of stabilizing CPI or core inflation only. The reason is that by raising interest rates when stock prices or real estate prices rise, and lowering them when these asset prices fall, central banks might be more successful in avoiding bubbles and crashes in asset prices.

Issuing in Measuring

Measuring inflation in an economy requires objective means of differentiating changes in nominal prices on a common set of goods and services, and distinguishing them from those price shifts resulting from changes in value such as volume, quality, or performance. For example, if the price of a 10 oz. can of corn changes from $0.90 to $1.00 over the course of a year, with no change in quality, then this price difference represents inflation. This single price change would not, however, represent general inflation in an overall economy. To measure overall inflation, the price change of a large “basket” of representative goods and services is measured. This is the purpose of a price index, which is the combined price of a “basket” of many goods and services. The combined price is the sum of the weighted average prices of items in the “basket”. A weighted price is calculated by multiplying the unit price of an item to the number of those items the average consumer purchases. Weighted pricing is a necessary means to measuring the impact of individual unit price changes on the economy’s overall inflation. The Consumer Price Index, for example, uses data collected by surveying households to determine what proportion of the typical consumer’s overall spending is spent on specific goods and services, and weights the average prices of those items accordingly. Those weighted average prices are combined to calculate the overall price. To better relate price changes over time, indexes typically choose a “base year” price and assign it a value of 100. Index prices in subsequent years are then expressed in relation to the base year price.[10]

Inflation measures are often modified over time, either for the relative weight of goods in the basket, or in the way in which goods and services from the present are compared with goods and services from the past. Over time adjustments are made to the type of goods and services selected in order to reflect changes in the sorts of goods and services purchased by ‘typical consumers’. New products may be introduced, older products disappear, the quality of existing products may change, and consumer preferences can shift. Both the sorts of goods and services which are included in the “basket” and the weighted price used in inflation measures will be changed over time in order to keep pace with the changing marketplace.

Inflation numbers are often seasonally adjusted in order to differentiate expected cyclical cost shifts. For example, home heating costs are expected to rise in colder months, and seasonal adjustments are often used when measuring for inflation to compensate for cyclical spikes in energy or fuel demand. Inflation numbers may be averaged or otherwise subjected to statistical techniques in order to remove statistical noise and volatility of individual prices.

When looking at inflation economic institutions may focus only on certain kinds of prices, or special indices, such as the core inflation index which is used by central banks to formulate monetary policy.

Most inflation indices are calculated from weighted averages of selected price changes. This necessarily introduces distortion, and can lead to legitimate disputes about what the true inflation rate is. This problem can be overcome by including all available price changes in the calculation, and then choosing the median value.

General Effects of Inflation

An increase in the general level of prices implies a decrease in the purchasing power of the currency. That is, when the general level of prices rises, each monetary unit buys fewer goods and services.[28] The effect of inflation is not distributed evenly in the economy, and as a consequence there are hidden costs to some and benefits to others from this decrease in the purchasing power of money. For example, with inflation, lenders or depositors who are paid a fixed rate of interest on loans or deposits will lose purchasing power from their interest earnings, while their borrowers benefit. Individuals or institutions with cash assets will experience a decline in the purchasing power of their holdings. Increases in payments to workers and pensioners often lag behind inflation, especially for those with fixed payments.

Increases in the price level (inflation) erodes the real value of money (the functional currency) and other items with an underlying monetary nature (e.g. loans and bonds). However, inflation has no effect on the real value of non-monetary items, (e.g. goods and commodities, gold, real estate).

Negative Effects

High or unpredictable inflation rates are regarded as harmful to an overall economy. They add inefficiencies in the market, and make it difficult for companies to budget or plan long-term. Inflation can act as a drag on productivity as companies are forced to shift resources away from products and services in order to focus on profit and losses from currency inflation. Uncertainty about the future purchasing power of money discourages investment and saving. And inflation can impose hidden tax increases, as inflated earnings push taxpayers into higher income tax rates unless the tax brackets are indexed to inflation.

With high inflation, purchasing power is redistributed from those on fixed nominal incomes, such as some pensioners whose pensions are not indexed to the price level, towards those with variable incomes whose earnings may better keep pace with the inflation.[10] This redistribution of purchasing power will also occur between international trading partners. Where fixed exchange rates are imposed, higher inflation in one economy than another will cause the first economy’s exports to become more expensive and affect the balance of trade.

There can also be negative impacts to trade from an increased instability in currency exchange prices caused by unpredictable inflation.

Cost-push inflation

High inflation can prompt employees to demand rapid wage increases, to keep up with consumer prices. Rising wages in turn can help fuel inflation. In the case of collective bargaining, wage growth will be set as a function of inflationary expectations, which will be higher when inflation is high. This can cause a wage spiral. In a sense, inflation begets further inflationary expectations, which beget further inflation.

Hoarding

People buy consumer durables as stores of wealth in the absence of viable alternatives as a means of getting rid of excess cash before it is devalued, creating shortages of the hoarded objects.

Hyperinflation

If inflation gets totally out of control (in the upward direction), it can grossly interfere with the normal workings of the economy, hurting its ability to supply goods. Hyperinflation can lead to the abandonment of the use of the country’s currency, leading to the inefficiencies of barter.

Allocate efficiency

A change in the supply or demand for a good will normally cause its relative price to change, signaling to buyers and sellers that they should re-allocate resources in response to the new market conditions. But when prices are constantly changing due to inflation, price changes due to genuine relative price signals are difficult to distinguish from price changes due to general inflation, so agents are slow to respond to them. The result is a loss of allocative efficiency.

Shoe leather cost

High inflation increases the opportunity cost of holding cash balances and can induce people to hold a greater portion of their assets in interest paying accounts. However, since cash is still needed in order to carry out transactions this means that more “trips to the bank” are necessary in order to make withdrawals, proverbially wearing out the “shoe leather” with each trip.

Menu costs

With high inflation, firms must change their prices often in order to keep up with economy-wide changes. But often changing prices is itself a costly activity whether explicitly, as with the need to print new menus, or implicitly.

Business cycles

According to the Austrian Business Cycle Theory, inflation sets off the business cycle. Austrian economists hold this to be the most damaging effect of inflation. According to Austrian theory, artificially low interest rates and the associated increase in the money supply lead to reckless, speculative borrowing, resulting in clusters of malinvestments, which eventually have to be liquidated as they become unsustainable.

Positive Effects:

Labor-market adjustments

Keynesians believe that nominal wages are slow to adjust downwards. This can lead to prolonged disequilibrium and high unemployment in the labor market. Since inflation would lower the real wage if nominal wages are kept constant, Keynesians argue that some inflation is good for the economy, as it would allow labor markets to reach equilibrium faster.

Debt relief

Debtors who have debts with a fixed nominal rate of interest will see a reduction in the “real” interest rate as the inflation rate rises. The “real” interest on a loan is the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. (R=n-i) For example if you take a loan where the stated interest rate is 6% and the inflation rate is at 3%, the real interest rate that you are paying for the loan is 3%. It would also hold true that if you had a loan at a fixed interest rate of 6% and the inflation rate jumped to 20% you would have a real interest rate of -14%. Banks and other lenders adjust for this inflation risk either by including an inflation premium in the costs of lending the money by creating a higher initial stated interest rate or by setting the interest at a variable rate.

Room to maneuver

The primary tools for controlling the money supply are the ability to set the discount rate, the rate at which banks can borrow from the central bank, and open market operations which are the central bank’s interventions into the bonds market with the aim of affecting the nominal interest rate. If an economy finds itself in a recession with already low, or even zero, nominal interest rates, then the bank cannot cut these rates further (since negative nominal interest rates are impossible) in order to stimulate the economy – this situation is known as a liquidity trap. A moderate level of inflation tends to ensure that nominal interest rates stay sufficiently above zero so that if the need arises the bank can cut the nominal interest rate.

Tobin effect

The Nobel Prize winning economist James Tobin at one point argued that a moderate level of inflation can increase investment in an economy leading to faster growth or at least a higher steady state level of income. This is due to the fact that inflation lowers the real return on monetary assets relative to real assets, such as physical capital. To avoid this effect of inflation, investors would switch from holding their assets as money (or a similar, susceptible-to-inflation, form) to investing in real capital projects. See Tobin monetary model

Causes of Inflation

Historically, a great deal of economic literature was concerned with the question of what causes inflation and what effect it has. There were different schools of thought as to the causes of inflation. Most can be divided into two broad areas: quality theories of inflation and quantity theories of inflation. The quality theory of inflation rests on the expectation of a seller accepting currency to be able to exchange that currency at a later time for goods that are desirable as a buyer. The quantity theory of inflation rests on the quantity equation of money, that relates the money supply, its velocity, and the nominal value of exchanges. Adam Smith and David Hume proposed a quantity theory of inflation for money, and a quality theory of inflation for production.[citation needed]

Currently, the quantity theory of money is widely accepted as an accurate model of inflation in the long run. Consequently, there is now broad agreement among economists that in the long run, the inflation rate is essentially dependent on the growth rate of money supply. However, in the short and medium term inflation may be affected by supply and demand pressures in the economy, and influenced by the relative elasticity of wages, prices and interest rates.[34] The question of whether the short-term effects last long enough to be important is the central topic of debate between monetarist and Keynesian economists. In monetarism prices and wages adjust quickly enough to make other factors merely marginal behavior on a general trend-line. In the Keynesian view, prices and wages adjust at different rates, and these differences have enough effects on real output to be “long term” in the view of people in an economy.

Keynesian view

Keynesian economic theory proposes that changes in money supply do not directly affect prices, and that visible inflation is the result of pressures in the economy expressing themselves in prices. The supply of money is a major, but not the only, cause of inflation.

There are three major types of inflation, as part of what Robert J. Gordon calls the “triangle model”

Demand-pull inflation is caused by increases in aggregate demand due to increased private and government spending, etc. Demand inflation is constructive to a faster rate of economic growth since the excess demand and favourable market conditions will stimulate investment and expansion.

Cost-push inflation, also called “supply shock inflation,” is caused by a drop in aggregate supply (potential output). This may be due to natural disasters, or increased prices of inputs. For example, a sudden decrease in the supply of oil, leading to increased oil prices, can cause cost-push inflation. Producers for whom oil is a part of their costs could then pass this on to consumers in the form of increased prices.

Built-in inflation is induced by adaptive expectations, and is often linked to the “price/wage spiral”. It involves workers trying to keep their wages up with prices (above the rate of inflation), and firms passing these higher labor costs on to their customers as higher prices, leading to a ‘vicious circle’. Built-in inflation reflects events in the past, and so might be seen as hangover inflation.

Demand-pull theory states that the rate of inflation accelerates whenever aggregate demand is increased beyond the ability of the economy to produce (its potential output). Hence, any factor that increases aggregate demand can cause inflation. However, in the long run, aggregate demand can be held above productive capacity only by increasing the quantity of money in circulation faster than the real growth rate of the economy. Another (although much less common) cause can be a rapid decline in the demand for money, as happened in Europe during the Black Death, or in the Japanese occupied territories just before the defeat of Japan in 1945.

The effect of money on inflation is most obvious when governments finance spending in a crisis, such as a civil war, by printing money excessively. This sometimes leads to hyperinflation, a condition where prices can double in a month or less. Money supply is also thought to play a major role in determining moderate levels of inflation, although there are differences of opinion on how important it is. For example, Monetarist economists believe that the link is very strong; Keynesian economists, by contrast, typically emphasize the role of aggregate demand in the economy rather than the money supply in determining inflation. That is, for Keynesians, the money supply is only one determinant of aggregate demand.

Some Keynesian economists also disagree with the notion that central banks fully control the money supply, arguing that central banks have little control, since the money supply adapts to the demand for bank credit issued by commercial banks. This is known as the theory of endogenous money, and has been advocated strongly by post-Keynesians as far back as the. 1960s.

Monetarist view

For more details on this topic, see Monetarists.

Monetarists believe the most significant factor influencing inflation or deflation is how fast the money supply grows or shrinks. They consider fiscal policy, or government spending and taxation, as ineffective in controlling inflation.[38] According to the famous monetarist economist Milton Friedman, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”[39] Some monetarists, however, will qualify this by making an exception for very short-term circumstances.

Monetarists assert that the empirical study of monetary history shows that inflation has always been a monetary phenomenon. The quantity theory of money, simply stated, says that any change the amount of money in a system will change the price level. This theory begins with the equation of exchange:

Where

M is the nominal quantity of money.

V is the velocity of money in final expenditures;

P is the general price level;

Q is an index of the real value of final expenditures;

In this formula, the general price level is related to the level of real economic activity (Q), the quantity of money (M) and the velocity of money (V). The formula is an identity because the velocity of money (V) is defined to be the ratio of final nominal expenditure to the quantity of money (M).

Monetarists assume that the velocity of money is unaffected by monetary policy (at least in the long run), and the real value of output is determined in the long run by the productive capacity of the economy. Under these assumptions, the primary driver of the change in the general price level is changes in the quantity of money. With exogenous velocity (that is, velocity being determined externally and not being influenced by monetary policy), the money supply determines the value of nominal output (which equals final expenditure) in the short run. In practice, velocity is not exogenous in the short run, and so the formula does not necessarily imply a stable short-run relationship between the money supply and nominal output. However, in the long run, changes in velocity are assumed to be determined by the evolution of the payments mechanism. If velocity is relatively unaffected by monetary policy, the long-run rate of increase in prices (the inflation rate) is equal to the long run growth rate of the money supply plus the exogenous long-run rate of velocity growth minus the long run growth rate of real output.

Unemployment

A connection between inflation and unemployment has been drawn since the emergence of large scale unemployment in the 19th century, and connections continue to be drawn this today. In Marxian economics, the unemployed serve as a reserve army of labour, which restrain wage inflation. In the 20th century, similar concepts in Keynesian economics include the NAIRU (Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment) and the Phillips curve.

Rational expectations theory

Main article: Rational expectations theory

Rational expectations theory holds that economic actors look rationally into the future when trying to maximize their well-being, and do not respond solely to immediate opportunity costs and pressures. In this view, while generally grounded in monetarism, future expectations and strategies are important for inflation as well.

A core assertion of rational expectations theory is that actors will seek to “head off” central-bank decisions by acting in ways that fulfill predictions of higher inflation. This means that central banks must establish their credibility in fighting inflation, or economic actors will make bets that the central bank will expand the money supply rapidly enough to prevent recession, even at the expense of exacerbating inflation. Thus, if a central bank has a reputation as being “soft” on inflation, when it announces a new policy of fighting inflation with restrictive monetary growth economic agents will not believe that the policy will persist; their inflationary expectations will remain high, and so will inflation. On the other hand, if the central bank has a reputation of being “tough” on inflation, then such a policy announcement will be believed and inflationary expectations will come down rapidly, thus allowing inflation itself to come down rapidly with minimal economic disruption.

Austrian theory

The Austrian School asserts that inflation is an increase in the money supply, rising prices are merely consequences and this semantic difference is important in defining inflation.[40] Austrian economists believe there is no material difference between the concepts of monetary inflation and general price inflation. Austrian economists measure monetary inflation by calculating the growth of new units of money that are available for immediate use in exchange, that have been created over time.[41][42][43] This interpretation of inflation implies that inflation is always a distinct action taken by the central government or its central bank, which permits or allows an increase in the money supply.[44] In addition to state-induced monetary expansion, the Austrian School also maintains that the effects of increasing the money supply are magnified by credit expansion, as a result of the fractional-reserve banking system employed in most economic and financial systems in the world.[45]

Austrians argue that the state uses inflation as one of the three means by which it can fund its activities (inflation tax), the other two being taxation and borrowing.[46] Various forms of military spending is often cited as a reason for resorting to inflation and borrowing, as this can be a short term way of acquiring marketable resources and is often favored by desperate, indebted governments

In other cases, Austrians argue that the government actually creates economic recessions and depressions, by creating artificial booms that distort the structure of production. The central bank may try to avoid or defer the widespread bankruptcies and insolvencies which cause economic recessions or depressions by artificially trying to “stimulate” the economy through “encouraging” money supply growth and further borrowing via artificially low interest rates.[48] Accordingly, many Austrian economists support the abolition of the central banks and the fractional-reserve banking system, and advocate returning to a 100 percent gold standard, or less frequently, free banking. They argue this would constrain unsustainable and volatile fractional-reserve banking practices, ensuring that money supply growth (and inflation) would never spiral out of control.

Inflation in Bangladesh

Overview of Inflation in Bangladesh

Substantial debate is still going on among economists regarding the causes of inflation. While monetarists view money supply as the only factor causing inflation through the demand channel, many believe in the supply side phenomena as important sources of inflation. According to the latter, movements in cost, either by restraining or easing the supply side, force inflation to move in a similar direction. History is replete with quite a few major examples of inflation that appeared to be the consequences of supply side disturbances. USA is said to have experienced remarkable inflation led by oil-shocks in 1971-74, 1979-80 and 1990 (Dornbush and Fischer 1994). Moreover, recent surge of global inflation is also believed to be an instance of inflation emanating from the oil crisis. In the Bangladesh economy, a series of incidents occurred over the recent couple of years prompting researchers to recognize the significant role of supply side phenomena in fueling inflation in Bangladesh. This policy note attempts to empirically examine the extent to which the recent inflationary

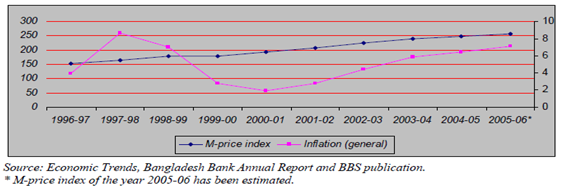

Analysis of the Recent Trends in Inflation

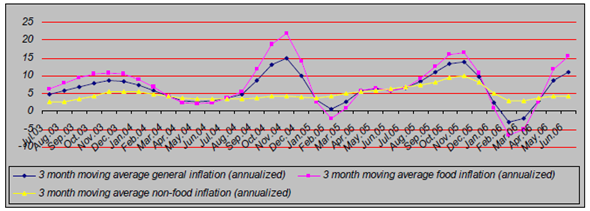

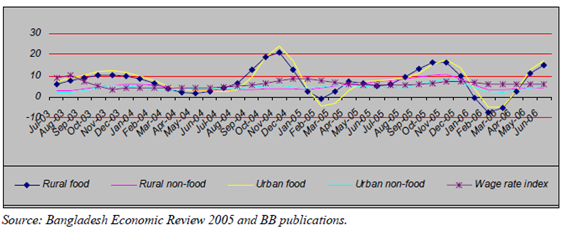

Figure-1 demonstrates the trends of Bangladesh inflation by depicting month-wise data of general, food and non-food consumer price inflation (annualized 3-month moving average) from FY03 to FY06. The purpose of using 3-month average instead of traditional

12-month in calculating inflation is to capture the dynamics implicit in the recent price data. It is observed from the figure that inflation maintained a highly erratic movement ranging from 14.82 percent in November ’04 to (-) 3.04 percent in February ’06. The volatility of the inflation behavior can be largely attributed to the food sector. The food inflation seems to have severely fluctuated within the range between (-) 6.75 in February ’06 to 21.88 in November ’04. By contrast, the non-food sector inflation showed a relatively steady pattern reflecting less seasonality. The fluctuation in food inflation is, in part, a manifestation of the typical seasonality in food production and the developments in the global commodity market. It would, therefore, be important to recognize the role of the cost/supply side phenomena in explaining Bangladesh inflation. As seen in the Figure-1, the inflation rate was over 5 percent during a significant number of months. It is also evident that the incidence of high food inflation is responsible for this situation. Except for a few instances, food inflation continued to be well above non-food inflation during the whole period. Moreover, whereas non-food inflation hardly exceeded 5 percent, the food inflation was higher than 5 percent almost as a rule. An analysis of the latest trends reveals that general and food inflation simultaneously started declining after November ‘05, reaching the lowest level in February ‘06 and then registering a sharp uptrend to end up with 11.02 and 15.53 percent respectively in the last month of FY06. The non-food inflation, although moderate, followed a similar pattern before reaching 4.3 percent at the end of the period. These trends appear to capture a broader seasonal behavior of prices in Bangladesh at least as seen in the data from FY04 to FY06. The surge in food inflation in the 4th quarter of FY06 does not appear to be related to seasonality, as the behavior of food prices in the comparable period of the previous two years, i.e., FY05 and FY04 indicates little volatility. The actual inflation in the latter dates ranged between 2.67 percent (FY04) and 6.27 percent (FY05). Further exploration of the source of the FY06 (4th quarter) price hike therefore appears urgent.

Bangladesh’s consumers’ price index (CPI) inflation rose to 9.06 percent in February 2010, up from 8.99 percent of the previous month; the rate of inflation went up by 0.07 percentage point in February, over that of the previous month, mainly because of the increase in prices of food items.

The inflationary pressures on economy has slightly gone up during the period due mainly to the increase in prices of food items in the local market as well as in the global markets.

The existing upward trend of inflation might continue in the third quarters but it particularly in food inflationary pressure would decline in the fourth quarters of the current fiscal year due to arrival of new rice crop along with the government’s market intervention.

Historical Trends of Inflation and Growth of Economy

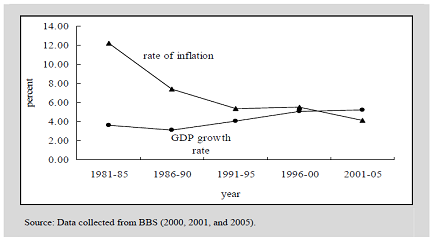

Bangladesh is the youngest country in the South Asian region. Following the launching of a series of comprehensive stabilization measures, the economy of Bangladesh mostly restored both robust economic growth and macro-economic stability in early 1990s from the backdrop of the deep macro-economic crisis of the period since independence (Bhattacharyya, 2004). In particular, the economy has experienced accelerated economic growth during the early 1990s in comparison with the 1980s. However, after that period, the economy experienced most severe exigency states like increasing inflationary pressures, deteriorating government’s budgetary balances and decreasing foreign exchange reserves (Mahmud, 1997). During the first half of the 1980s the country experienced a double-digit episode of inflation while the growth rate of GDP was below 4-percent level as illustrated in

Figure1. The GDP growth rate declined moderately during the second half of 1980s when inflation rate gradually decreased to below 8-percent. However, a moderate rate of inflation and an increasing rate of GDP growth are observed throughout the 1990s. Throughout the first half of the 1990s, inflation rate was, on average, 5.37 percent, while GDP growth rate was 4.06 percent. Although inflation rate increased, on average, to 5.52 percent in the second half of the 1990s, the growth rate of GDP continued to increase. The increasing trend of inflation rate during the latter half of 1990s had been corrected since the beginning of the new decade after 1990s and was observed at 4.14 percent, on average, during 2001 to 2005, when growth rate of GDP was, on average, 5.19 percent.

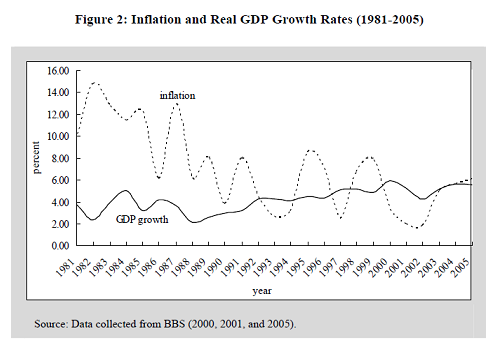

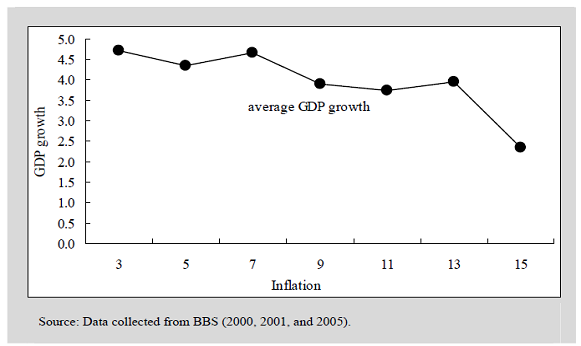

Figure 2 depicts the historical trends of inflation rate and real GDP growth rate of Bangladesh during the period of 1981 to 2005. Although it is unwise to conclude anything simply on the basis of a visual inspection of Figure 2, however, it illustrates more or less an inverse relationship between rate of inflation and GDP growth rate in Bangladesh throughout this period. Moreover, to understand the historical nature of the relationship between inflation and economic growth in Bangladesh more accurately, the sample covering 1981 to 2005 is grouped into 7 observations. Initially, the range of inflation is selected on the basis of the maximum and minimum levels of inflation from the whole sample. For instance, if inflation rate is 3-percent or less, it is assigned at level 3. Similarly, the level is 5, if inflation rate is more than 3-percent but less than or equal to 5-percent. Subsequently, within this range of inflation, average GDP growth rates are calculated against each linear level of inflation. For illustration, what is the average GDP growth rate when inflation rates are 3 percent or less during the period from 1981 to 2005 and so on? In this context,

Figure 3 illustrates a positive relationship between inflation and GDP growth up to the inflation rate of 7 percent (approximately) and a negative relationship is observed after that level of inflation rate.

Reasons for inflation in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has no specific reason of inflation at present. Inflation is increasing more and more for several reasons. But all reasons are not equally important. Some reasons influence more and some reasons influence less. Our economists, businessmen and other involved parties with economics have identified nine reasons of inflation after the observation of last several months.

Economist, policy makers and multilateral capital donors have different explanations about the causes of inflation in countries like Bangladesh. A brief look at a few of such explanations merits attention for shaping and re-shaping of appropriate policies to help curb inflation. Here below is a brief critical overview of such explanations.

One of the causes of inflation, explained as such, relates to food prices in the international market. Bangladesh being a food importing country, any rise in food prices in the world market can push up the domestic prices of those commodities. In the not too distant past, the prices of essential commodities, like rice, wheat and edible oil, increased significantly in the international markets. So, domestic prices of those items shot up phenomenally then.

Then the link between rising prosperity and inflation is sought to be proved by many. Despite all its problems, Bangladesh has been performing well, in terms of economic growth over the last 10 years. Its gross domestic product (GDP) base is not small, in absolute volume terms. It is the 50th largest economy in a sample of 177 countries. Not many developing countries have grown faster than Bangladesh with bigger GDP volumes since the early 1990s. Those who seek to link inflation and GDP growth performance state that the high growth rate of GDP and the per capita GDP in particular has led to the creation of excess demand in the Bangladesh economy. This has resulted in a demand-pull inflation.

Then there is the growth of money supply that is directly related to the price situation. ‘Inflation is a monetary phenomenon’, so is explained by a good number of economists as well as some of the donor agencies. It is, thus, stated to be caused by the excessive supply of money in the economy. Bangladesh Bank has otherwise been found to be guided by the monetarist approach to inflation — and that is not without some good reason. If has been following a rather “cautious” monetary policy. Many consider it as a pragmatic step.

Labor Cost

Wage, the labor cost, is often seen as the key reason behind cost-push inflation. Wage increase without any commensurate increase in productivity kicks off a wage-price spiral, allowing for sustained inflation. Analysis of the movements of nominal wage rate inflation generally gives an idea about the labor cost scenario. The time path of the nominal wage inflation portrayed in Figure-2 suggests that in Bangladesh, the wage inflation has been pretty stable at above 5 percent per annum with some short-term fluctuations over the period from July ‘03 to June ‘06. Under the assumption of little or no improvement of workers’ productivity growth, wage inflation at such high level is an indication of cost escalation over time. However, whether the accelerated cost has translated into inflation is not clearly observable in the figure. An analysis of the correlation matrix presented in Box-1 is useful in exploring the precise link between labor cost and inflation. It is seen from the matrix that wage rate inflation has statistically significant association only with rural food inflation (coefficient of 0.22) at the 10-percent level of significance during the period from FY00 to FY06. It, therefore, appears that wage inflation cannot be a dominant factor in explaining the price behavior in Bangladesh. This is what one would normally expect in a labor surplus environment.

Fig: Labor Cost and Inflation (annualized 3-month moving average)

Import Cost Typically import occupies a significant place in the Bangladesh economy, accounting for as high as above 20 percent or more of GDP in FY06. At the margin, most of the essential food items (for example, sugar, rice, wheat, onion and edible oil) and, more generally, machineries, intermediate goods and raw materials used in production are imported. Cost of imports can, therefore, be expected to have a substantial influence on domestic inflation directly (through final goods) or indirectly (through intermediate goods). According to available statistics, import price index (MPI) of Bangladesh has continuously soared over time which is reflected by an almost straight upward curve in

Figure: Import Cost and Inflation (12-month moving average)

Figure-3. The figure also depicts the inflation trend. Comparison among the trends in import price index and inflation provides an observation about the relationship between these indices. It is seen that although during the period from FY97 to FY01 the relationship is somewhat ambiguous, the co-movement from FY01 onward appears robust. To verify this relationship, a separate correlation matrix has been constructed using yearly data for the period from FY01 to FY06. The correlation analysis, presented in the Box-2, reveals that while the relationships between import price index and categories of non-food inflation (urban and rural) are insignificant, the former is found to have economically as well as statistically highly significant association with the categories of food inflation (urban and rural). The positive association is suggestive of the hypothesis that the surge in inflation is in part a supply side phenomenon. Evidently, the reasons for increase in import price are twofold- exchange rate depreciation and increase in international commodity prices.

Exchange Rate

Exchange rate exerts inflationary pressure mainly via import prices. Historically, exchange rate in Bangladesh exhibited steady increase over time. The period average BDT-USD exchange rate was recorded at 61.39 during FY05 in comparison to 40.20 and 50.31 during FY95 and FY00 respectively. The comparable FY06 figure rose to 67.08 as the currency remained under pressure during the first three quarters of the fiscal year. The inflation in the fourth quarter of FY06 (Figure-1) seems to have been prompted by a sharp increase in the exchange rate throughout the second quarter and part of the third quarter of the same fiscal. The contribution of the exchange rate depreciation to inflationary pressure has been attested to by the results of the said correlation analysis (Box-1). Accordingly, exchange rate is seen to be uniformly correlated with all categories of inflation (rural food, rural non-food, urban food and urban non-food) at the 1-percent level of significance, the coefficients being 0.34, 0.29, 0.36 and 0.37 respectively.

Oil Price

Being a fundamental input of production, oil constitutes a significant portion of production cost in every sector of the economy. In spite of some recent adjustments in the administered price of energy products, much of the increased cost of imported fuel has not been passed on to end users, especially on diesel and kerosene. However, the correlation analysis (Box-1) provides evidence that an increase in the diesel price (proxy for oil price) stimulates inflation via increases in both food and non-food prices in both urban and rural areas. This is plausibly due to the fact that diesel is used intensively regardless of sector (food or non-food, urban or rural). The correlation coefficients are estimated as 0.36, 0.30, 0.41 and 0.32 for rural food, rural non-food, urban food and urban non-food sector respectively.

Supply Shortage

Production in agriculture and fisheries sectors in Bangladesh is still subject to the whims of nature to a notable extent. It has been claimed that one of the main causes of the high food inflation throughout the FY05 was poor harvest of aus, aman and wheat crops. The yearly production of these three crops went down by 18.12, 14.76 and 22.11 percent respectively in FY05 over the FY04.An instance of price hike due to this fall of production is that the price (per kg) of aman rice rose within the range of BDT 16 to 19 in FY05 from the range of BDT 14 to 16 in FY04.

Market Syndication

Unfair cartel among the suppliers might seriously hamper the course of the economy by engendering inflation via the creation of a false supply shortage even during a period of robust growth in production. Such an undesirable event allegedly occurred in FY06 when the food inflation remained high (7.76 percent) in the same fiscal year despite the growth in food production (4.49 percentvis-à-vis 2.21 percent in FY05). Monopolistic control of several food items such as sugar, onion, pulses and edible oil by market syndication seems to have led this situation. Obviously such manipulation is a type of supply side disturbance.

Policy Implications

The above analysis carries an important signal for the policy makers. In an effort to subdue inflation they have to keep a sharp eye not only on the demand phenomena, but also on the cost behavior in the relevant period. Unfortunately, there is hardly any market oriented policy move on the part of fiscal or monetary authorities that can be taken for checking the cost induced inflation. On the fiscal side, although cutting down of the indirect tax on commodities is often proposed as a remedial measure, it only makes a temporary contribution to reducing inflation. Long term continuation of such policy may cause continuous erosion of the government exchequer. Some also argue in favor of government control on wage increases that are not supported by the corresponding increase in productivity to resist wage-price spiral. In Bangladesh, however, the presence of powerful trade unions tends to render the implementation of such control almost impossible. On a positive note, however, our analysis did not find any noteworthy impact of wage growth on inflation. It is widely recognized, however, that government can effectively use its legal powers to break up the market syndication and thus improve competitiveness of the distribution network.

On the monetary side, in the absence of any direct controlling instrument, Bangladesh Bank can initiate some case specific counter-action. Bangladesh Bank can take over some responsibilities such as monitoring modalities of Letter of Credit (L/C) operation so that market forces determines the exchange rate in a process that remains free from much speculative transactions. One example of a move in this direction is that the Governor of Bangladesh Bank, in a recent monthly bankers’ meeting, advised the bankers to settle their liabilities against local L/C in foreign exchange through Bangladesh Bank clearing account instead of their nostro account. It is estimated that BDT 200 million worth of foreign exchange will be saved if this advice comes into effect. Though indirectly, Control Mechanism of Inflation

Policies to control inflation need to focus on the underlying causes of inflation in the economy. For example if the main cause is excess demand for goods and services, then government policy should look to reduce the level of aggregate demand. If cost-push inflation is the root cause, production costs need to be controlled for the problem to be reduced.

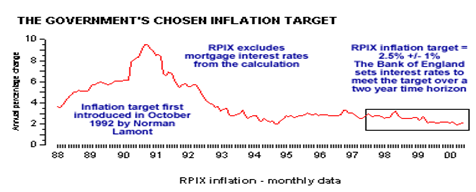

Monetary Policy – Interest Rates

Since May 1997, the Bank of England has had operational independence in the setting of official interest rates in the United Kingdom. They set interest rates with the aim of keeping inflation under control over the next two years.

Monetary policy can control the growth of demand through an increase in interest rates and a contraction in the real money supply. For example, in the late 1980s, interest rates went up to 15% because of the excessive growth in the economy and contributed to the recession of the early 1990s. This is shown in the chart above

Higher interest rates reduce aggregate demand in three ways;

- Discouraging borrowing by both households and companies

- Increasing the rate of saving (the opportunity cost of spending has increased)

- The rise in mortgage interest payments will reduce homeowners’ real ‘effective’ disposable income and their ability to spend. Increased mortgage costs will also reduce market demand in the housing market

Business investment may also fall, as the cost of borrowing funds will increase. Some planned investment projects will now become unprofitable and, as a result, aggregate demand will fall.

Higher interest rates could also be used to limit monetary inflation. A rise in real interest rates should reduce the demand for lending and therefore reduce the growth of broad money.

Fiscal Policy

- Higher direct taxes (causing a fall in disposable income)

- Lower Government spending

- A reduction in the amount the government sector borrows each year (PSNCR)

These fiscal policies increase the rate of leakages from the circular flow and reduce injections into the circular flow of income and will reduce demand pull inflation at the cost of slower growth and unemployment.

An Appreciation Of The Exchange Rate

An appreciation in the pound sterling makes British exports more expensive and should reduce the volume of exports and aggregate demand. It also provides UK firms with an incentive to keep costs down to remain competitive in the world market. A stronger pound reduces import prices. And this makes firms’ raw materials and components cheaper; therefore helping them control costs.

A rise in the value of the exchange rate might be achieved by an increase in interest rates or through the purchase of sterling via Central Bank intervention in the foreign exchange markets.

Direct Wage Controls – Incomes Policies

Incomes policies (or direct wage controls) set limits on the rate of growth of wages and have the potential to reduce cost inflation. The Government has not used such a policy since the late 1970s, but it does still try to influence wage growth by restricting pay rises in the public sector and by setting cash limits for the pay of public sector employees.

In the private sector the government may try moral suasion to persuade firms and employees to exercise moderation in wage negotiations. This is rarely sufficient on its own. Wage inflation normally falls when the economy is heading into recession and unemployment starts to rise. This causes greater job insecurity and some workers may trade off lower pay claims for some degree of employment protection.

Long-Term Policies to Control Inflation

Labour Market Reforms

The weakening of trade union power, the growth of part-time and temporary working along with the expansion of flexible working hours are all moves that have increased flexibility in the labour market. If this does allow firms to control their labour costs it may reduce cost push inflationary pressure.

Certainly in recent years the UK economy has not seen the acceleration in wage inflation normally associated with several years of sustained economic growth and falling inflation. One reason is that rising job insecurity inside a flexible labour market has tilted the balance of power away from employees towards employers.

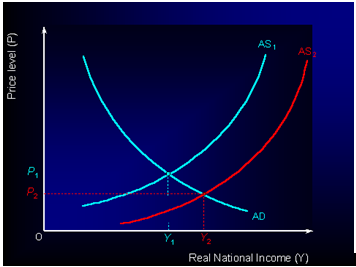

Supply Side Reforms

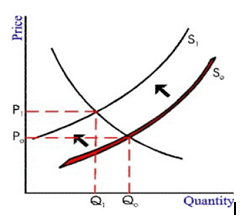

If a greater output can be produced at a lower cost per unit, then the economy can achieve sustained economic growth without inflation. An increase in aggregate supply is often a key long term objective of Government economic policy. In the diagram below we see the benefits of an outward shift in the short run aggregate supply curve. The equilibrium level of real national income increases and the average price level falls.

Supply side reforms seek to increase the productive capacity of the economy in the long run and raise the trend rate of growth of labour and capital productivity. A number of supply-side policies have been introduced into the British economy in recent years. Productivity gains help to control unit labour costs (an important cause of cost-push inflation) and put less pressure on producers to raise their prices.

The key to controlling inflation in the long run is for the authorities to keep control of aggregate demand (through fiscal and monetary policy) and at the same time seek to achieve improvements to the supply side of the economy. The credibility of inflation control policies can often be enhanced by the introduction of inflation targets.

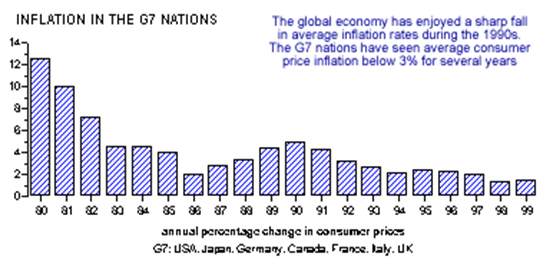

Many countries operate inflation targets. The number of countries with explicit inflation targets increased almost sevenfold between 1990 and 1998 from 8 to 54. Since October 1992, the British Government has pursued an explicit inflation target for the economy. When Labor came to power in May 1997, they set the target for RPIX inflation at 2.5% (+ or – 1%) for the next five years.

The Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee sets interest rates with a view to meeting the inflation target over the next two years. If RPIX inflation moves 1% either side of the 2.5% target, the Governor of the Bank has to write an open letter to the Chancellor explaining the reasons for the inflation undershoot / overshoot and the steps the MPC are taking to bring inflation within the target zone again. Over the last seven years, RPIX inflation in the UK has stayed within 1% of the target measure. The 1990s has seen a return to the low, stable inflation last seen in the 1960s.

Advantages of an Inflation Target

An effective inflation target can have several economic benefits:

- It can reduce inflationary expectations if people believe a low inflation target will be met. This will then reflect in the wage demands of people in work. If employees expect low inflation they may be prepared to accept a slower growth of pay. This reduces the risk of cost-push inflation in the economy. A fall in inflation expectations can cause an inward shift of the Phillips Curve.

- A target gives monetary policy a clear anchor and improves the accountability and transparency of economic policy-making. The quarterly Bank of England Inflation Report is a highly detailed assessment of economic trends and the Bank’s best guess about future movements in inflation. All A-Level Economists and Degree students should make a habit of reading it!

- Sustained low inflation improves prospects for higher levels of capital investment in both manufacturing and service industries. This is because businesses will not demand such high nominal rates of return on potential investment projects if they believe that inflation will remain low and stable.

- A Bank of England report in August 1999 argued that inflation targets have been successful in reducing inflation expectations and improving people’s understanding of the inflation process

Potential Disadvantages of An Inflation Target

- The main drawback is that a narrow inflation target is risky for an open economy such as the UK. Am open economy relies heavily on exports and imports and imposes few restrictions on free trade between countries.

- Fluctuations in the exchange rate and changes in inflation rates in other countries or in the prices of imported goods and services can push the domestic inflation rate higher and lead to increases in interest rates. Higher interest rates have the effect of damaging economic growth and employment.

- There is a danger that strict adherence to a tough inflation target may lead to the economy operating well below its long-run productive potential. This can create much higher unemployment – which in itself generates economic and social costs.

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy involves government expenditure and revenue, through taxes, borrowing and printing money. Anti-inflationary fiscal policy would focus on with- drawing purchasing power from the public so that they spend less, relieving the upward pressure on prices. This can be done by raising taxes and borrowing from the public without spending the proceeds. As the origin of inflation in most developing countries has been increasing government claim on productive resources (required for public sector projects), a decrease in government expenditure leaving taxes undiminished may still be more effective. Fiscal policy is regarded as ‘deliberate manipulation of the relation between government expenditure and government receipts with a view to maneuvering the level of aggregate demand in the desired direction”

Manipulation of aggregate demand is not the only way fiscal policy can target inflation. Spending money in a way that increases the supply of goods and services can also help governments check the rising trend in prices.

It has been rightly observed that inflation as we know it (i.e. a sustained rise in prices) is a modern phenomenon. The price level was stable for nearly a century till 1914. But a number of factors, among which debt financing of the two world wars was only one, caused most countries to experience rising prices since the middle of the century till the eighties. The same period also saw a phenomenal rise in public spending which globally reached 43% of the GDP by 1980. As a result inflation is commonly perceived as a consequence of rising public expenditure. This, however, may not always be true.4 One has to examine specific cases to arrive at a conclusion.

Prevention and Control

There are two significant differences between fiscal policies designed to control already existing inflation and those designed to prevent inflation from afflicting an economy which at the time is free of inflation. The first difference relates to time horizon and the speed at which a policy measure is carried out. The second relates to the size of the change required in the relevant variables e.g. government expenditure, taxes, etc. Policies designed to control inflation have to have an impact now. They must be fast acting showing their results in a matter of months. This in turn may require big reduction in government expenditure, large increases in taxes, huge amounts of domestic borrowing etc. Given these measures successfully implemented over a short period of time aggregate demand will decrease and the trend of prices to rise will be checked. The big question is how far it is possible and desirable to do so.

Let us have a look at the way government decides how much to spend. Part of government expenditure relates to the core of governance, no government can function without these. They can be reduced if they are inflated but there is a limit to such reduction. Expenditure on salaries and offices of the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government come under this category.

Reduction in Public Expenditure

It is only when we come to the other public goods and the welfare activities of the government that reduction in government expenditure becomes a real possibility. But the actual scope of such reduction depends on the historical path followed by (the increase in) government expenditure. Modern day governments have shown little ability to reduce expenditure on education and health care. For a developing country the idea of reducing expenditure on education and health care is still the less appealing. Reducing the current levels of expenditure on education and health care are nowhere a real option. In fact any attempt to do so would be economically disastrous and politically suicidal for the regime.

It has been rightly observed that public expenditure increases as the national output increases. It is very difficult to predict a reduction in public expenditure in an economy where the real output is increasing.

Increase in Tax Revenues

One should also consider the possibility of tax evasion and even coaxing people to pay ‘donations’ —- over and above taxes — to enable their government do good things for them. The likely gains in revenue terms are however, likely to be more than counterbalanced by two other certain changes. There are certain indirect taxes on basic necessities of life. Then there is mandatory lowering of tariffs and custom duties as part of ones belonging to a world set to reduce them globally. Let us now turn to the other policy measure, withdrawal of purchasing power from the public through increased taxation and domestic borrowing not accompanied by a corresponding rise in public expenditure. This in fact is only a textbook proposition insofar as the developing countries are concerned. These countries are not able to meet even current levels of public expenditure through all the taxes and domestic borrowing they can manage, thereby taking recourse to printing new money. As regards an Islamic economy domestic borrowing ceases to be an option as no interest can be paid to the lenders. A resort to compulsory borrowing free of interest as suggested by some1 would be hardly feasible in political terms. Additional taxation with the sole purpose of withdrawing some purchasing power and freezing it implies that the money should be paid back when the time comes to defreeze it. That makes it akin to compulsory borrowing. There is no empirical evidence of any developing country ever having adopted these policies successfully.

Increasing the Supply of Goods and Services

That leaves us with the last option noted under the heading fiscal policy: spending money in a way that increases supply of goods and services. This spending does not have to be done by the government itself. Tax reduction that encourages private investment may serve the same purpose. Lowering corporation taxes and lowering or scrapping capital gains taxes, even scaling down the income taxes may boost production by increasing the incentive to work and the incentive to save. Another possible measure is to restructure the subsidies in favor of the intermediate industries whose products are needed for expanding the production of consumer goods. Building the infrastructure — roads, bridges, irrigation systems, electricity and telecommunication, etc. — at public cost and making them available to the private sector at affordable prices has also been a favorite policy of mid-century developmental planning. These can be adopted after due consideration of the lessons from the past.

Even though each one of these policies is slow acting and of modest impact their cumulative impact over time would be significant. There can be no definite way to check the rising trend in prices than to arrange for increasing the supply of the very things whose prices are increasing. Fiscal policy has no other way to make a durable contribution to solve the problem of inflation since the two other options examined above are limited in scope and not practical. Unlike the impact of anti-inflationary monetary policy which may be immediate but temporary, the impact of supply increasing fiscal policies is slow but durable.

In seems the scope for reducing public expenditure from their current levels is very limited insofar the contemporary Muslim countries are concerned. The same applies to the possibility of withdrawing purchasing power from the public without spending the proceeds. This leaves us with the slow acting option of trying to maneuver public expenditure and taxation in a way that increases the incentives to work, save and invest and / or directly contributes to increasing the supply of goods and services.

Economic policies taken by Bangladesh Government

The control of inflation has become one of the dominant objectives of government economic policy in many countries. Effective policies to control inflation need to focus on the underlying causes of inflation in the economy. For example if the main cause is excess demand for goods and services, then government policy should look to reduce the level of aggregate demand. If cost-push inflation is the root cause, production costs need to be controlled for the problem to be reduced.

- · Procurement and Distribution of Food grains by Public Sector: To increase the operation of the PFDS, the government decided to intensify public sector procurement from domestic sources, import 8 lac metric tonnes of food grains and to increase distribution under non-priced channels such as TR, GR, FFW and VGD.

- · One important fiscal measure taken by the government was to reduce import duties and para-tarrifs. The governments decided to withdraw CD on crude edible oil and lentils, as well as continue the duty treatment of rice, wheat, onion, matar dal and chola dal. Zero customs duty on crude edible oil and lentils has also been introduced.

- · Subsidy for diesel and Electricity used in Irrigation: Bangladesh Government has decided to provide Tk. 7.5 Billion as an subsidy for diesel used for irrigation purposes and to continue with the 20% subsidy provided for electricity used in irrigation.

Conclusion:

Inflation was there always and it will be but the fact is the inflation should be controlled it should be kept in a limit. The government of Bangladesh should take necessary steps to keep it under control. Between the two mitigation techniques Bangladesh Government should keep its eye on the underlying reasons behind inflation. Bangladesh can mitigate the rising food price if Government can take necessary steps in increasing the production of food grains in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Govt. also has to increase employment facility by increasing the number of investment in production sector. If more industrialization can be occurred then the GDP will increase and the inflation will be mitigated. Bangladesh bank and also use the monetary weapons that they have over inflation. So, controlling of inflation for short term is not what our country needs to emphasize rather the long-term solution is needed.