The dreadful planet Venus is famous for its extremely thick atmosphere, crushingly high air pressure, and surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead. In other words, its surface conditions are among the most hostile in the entire solar system.

However, according to the traditional definition of “habitable zone,” Venus is located within this “Goldilocks” zone. This is due to the fact that the present definition of habitable zone only considers the amount of sunlight reaching a planet. If there is too much or too little, liquid water cannot exist on the surface, and the planet is thus unsuitable for life. Venus is livable, which means it might potentially support liquid water, according to this simple requirement. But it clearly does not. So does this make Venus-like planets rare, or should we start questioning our definitions?

New research using simple models of the evolution of the atmospheres of Venus-like planets has found that these worlds are frighteningly common.

The runaway greenhouse

Astronomers aren’t sure what happened on Venus so long ago. We can only surmise how this planet became so bad because we don’t have detailed measurements of its surface.

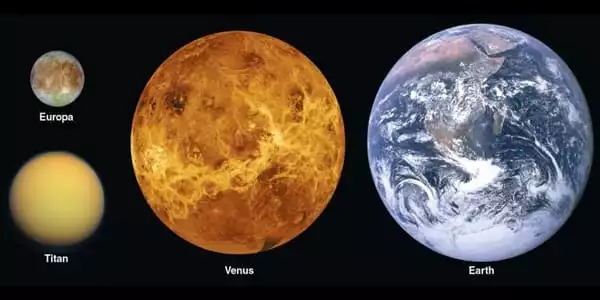

Because Venus is nearly the same size as Earth and originated in around the same region, many planetary scientists believe it began quite similarly to our own planet, with roughly the same amounts of all the critical ingredients: carbon, oxygen, silicon… and water. Venus most certainly began with pools — possibly oceans — of liquid water on its surface, surrounded by a lovely atmosphere.

And then, something went very, very wrong.

A protracted era of active volcanism may have damaged Venus’ atmosphere beyond repair. Perhaps it was simply the sun’s natural progression, with increased illumination draining all the water on the surface. Perhaps it was a process that we are still learning about.

Whatever the specific mechanism was, Venus had a runaway greenhouse effect. With each increase in atmospheric pressure, temperatures soared, causing even more gases to enter the atmosphere and feed off one other in a destructive cycle. Once enough gases had accumulated in the atmosphere, Venus was unable to cool, trapping practically all the solar light. If there was any life in those primordial oceans, it certainly wasn’t having a good time anymore.

The living world

The first stage in our search for habitable worlds is to locate planets that are in their stars’ habitable zones, because that is where Earth is in its orbit around the sun, and Earth is the only location in the universe known to contain life as we know it. Yes, different types of life may exist in the universe. However, because Earth-like life is the most easily recognized, it makes an easy target.

However, planets are complex, making it difficult to establish a clear definition of the habitable zone. Venus should have water on its surface because it receives just the appropriate amount of sunlight.

A group of scientists has now sought to locate the boundary between Earth-like and Venus-like planets. They used a rather rudimentary model of planetary atmospheres and the type of radiation those planets would get from various types of stars in a report just released to the preprint database arXiv.

The researchers began with an Earth-like mix of atmospheric gases (mostly nitrogen, with a bit of carbon dioxide) for each setup, with different types of stars and different orbits around those stars, and gradually increased the amount of carbon dioxide to simulate the beginnings of a runaway greenhouse effect. They then let the model evolve to see what happened to the composition of the atmosphere over time.

They declared a model planet “Venus-like” when the models blew up and a true runaway began. If the model planet stabilized and self-regulated, avoiding a runaway scenario, they designated it as “Earth-like” and still within the habitable zone.

The banality of evil

The researchers discovered that Venus-like worlds are unexpectedly frequent, and that large portions of the habitable zone may be inhospitable to life. For example, the typical habitable zone around a sun-like star ranges from 95 to 167 percent of Earth’s orbital radius. However, these models discovered that the outer border of the “Venus zone” reached 135 percent of Earth’s orbit, implying that our planet may one day experience its own runaway greenhouse effect!

F-type stars, with masses ranging from 1.0 to 1.4 times that of the sun, fared the best, with around 40% of their habitable zones surviving. Small red dwarf stars fared the worst because they produce the majority of their energy in infrared regions that are easily blocked by atmospheric molecules. For these stars, the Venus zone consumed all but the outermost edges of the habitable zone.

However, all hope is not gone. These models are basic, whereas planets are complicated. Not every planet that is capable of entering a runaway greenhouse cycle must. Interesting atmospheric mixing, shielding from planetary magnetic fields, increased amounts of water, or plate tectonics could all change planet trajectories. Not every Venus-like planet is doomed to become a terrible world, but we must exercise caution when looking for Earth-like planets.