SAOTA’s founder Stefan Antoni likes recounting an incident that happened while the company’s Cape Town office was being built. He became aware that a portion of the view of Table Mountain would be blocked as the roof was being lowered into place. Work ceased. To maintain a clear view of the city’s recognizable flat-top mountain, the entire roof had to be reconstructed.

“To capture that view was crucial,” Antoni said. “If you had not, you had erred terribly.”

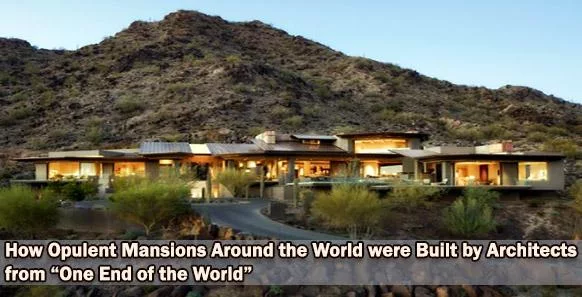

The story encapsulates Antoni’s philosophy, which invites nature’s grandeur into equally opulent homes. Through creative use of space and framing, these buildings can give the impression that you are in control of an entire mountain, an expanse of water, or an entire city. It’s not surprising they broke real estate records.

Its customers appear in groups in South Africa and the US, but also in countries like Russia, Indonesia, and Nigeria, putting SAOTA’s knowledge to the test in a range of situations. McMansions, these are certainly not: a SAOTA-designed house on Ocean View Drive in Cape Town’s Bantry Bay sold for 290 million rand in 2016 ($20.2 million at the time) reportedly becoming the most expensive private home sold in Africa. “We try to tell our clients that good design has got great value,” said Antoni.

Now, after over 30 years in the business, the firm has produced its first book, “Light, Space, Life,” which showcases some of its most memorable designs. “(The book’s purpose is) to capture a mindset; a thought up to a certain point,” said Antoni, who also described it as a “springboard” for new ideas. So where could the South African firm go from here?

Structural gymnastics at the bottom of Africa

Antoni began plying his trade in the mid 1980s, when apartheid and cultural boycotts meant South Africa was largely cut off from the world. He says his firm rode the wave of a “mini renaissance” in a post-apartheid creative boom, but Cape Town remained in many ways on architecture’s periphery, “at one end of the world, at the very bottom of Africa looking up.”

“You are very aware that you’re not at the center of the universe,” Antoni said, “and if you want to make any kind of impact, you have to do something exceptionally well.”

The distinctive landscape of Cape Town, situated between the sea and the mountains and blasted by two distinct seasonal winds, served as an incubator for SAOTA’s style.

Dr. Philippa Tumubweinee, an academic at the University of Cape Town School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, says SAOTA brought an innovative approach to the country’s architecture. “It’s structural gymnastics. It’s very long cantilevers, concrete and clean space which is not necessarily a new aesthetic, but within a South African context, it was relatively new,” she explained.

Cape Town’s sloping Atlantic Seaboard, where many SAOTA projects sprang up, also served as a shop window. “It’s quite visible,” Antoni said. “People can see (a) house, which works in our favor. Because if you design something that’s interesting or beautiful, people do notice.”

Work in South Africa slowed down in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, but SAOTA quickly resumed receiving commissions from all over the world. According to Mark Bullivant, a principle architect at SAOTA, by 2012 it has created its first project in Miami, Florida, a house on the Venetian Causeway designed to resemble the deck of a superyacht.

“It was this project that really set everything on its path for us,” he added. SAOTA picked up further work in Florida, along with New York, California, Colorado, and Texas.

Bullivant said places with a Mediterranean climate Los Angeles, for example are a natural fit for exporting what he calls a “Cape Town building,” while others, like the Middle East, require a different approach.

“We always say that our goal is to design a building that looks like it’s always belonged there,” he explained. For example, in Bali, SAOTA used local black andesite stone instead of concrete, and an upcoming project in Phoenix, Arizona, on the slopes of Camelback Mountain, will utilize rammed earth walls “to create a connection the site.”

“There’s a fundamental cultural aspect to the different places, in the way that people live,” said Bullivant. “But also, from a sustainable point of view, we’d like to use as much local materials (as possible).”

Designing for the one percent

300 employees work for SAOTA today, collaborating on projects with architects from all around the world.

Tumubweinee thinks SAOTA’s success has been largely attributable to its emphasis on the early stages of concept and design creation rather than the construction process. “On the surface (it) seems like a strange thing to do, because as the architect, you want to have control of the final product. But it means that they can do a lot more projects at the same time without having an incredibly large staff,” she explained.

“They disrupted the professional practice in the country,” she added.

The US real estate market has further burnished SAOTA’s portfolio. SAOTA-designed “Pine Tree,” in Miami sold for $22.5 million in 2017, according to the firm, and “Hillside,” a key location in Netflix Los Angeles realtor series “Selling Sunset,” sold for $35.5 million in 2019. In Miami earlier this year, an estate on Star Island containing two houses, the larger of which was designed by SAOTA, was listed for a reported $90 million.

Back in Cape Town, a city of stark economic contrasts and disparate living conditions, Tumubweinee said SAOTA’s ultra-high-end projects have not been without criticism. “But,” she said, “even though the criticism is valid and I do agree with that critique at some point, especially with architectural practice, there’s got to be a space in which people push the practice beyond.” It’s the “one percent,” she added, “who can afford innovation, who can afford for (architects) to experiment.”

Antoni insisted he is more interested in the worth owners place on their SAOTA homes than their financial value.

“Clients say, ‘you’ve ruined our lives,’” Antoni said, smiling, “we go on holidays now and we don’t enjoy them that much anymore we want to go back home.”

“In a way, that sort of sums it up,” he added. “A house or home is not just a functional living space, it should have an emotive quality … it should be a place where you can fulfill all your dreams and all your aspirations.”