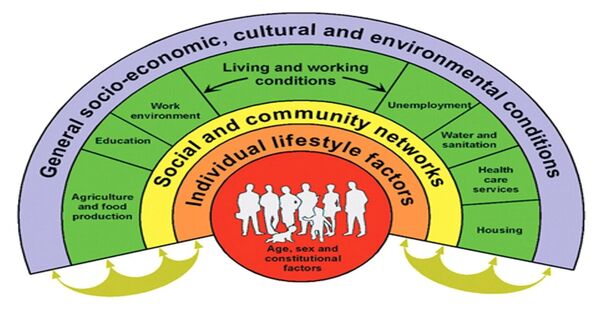

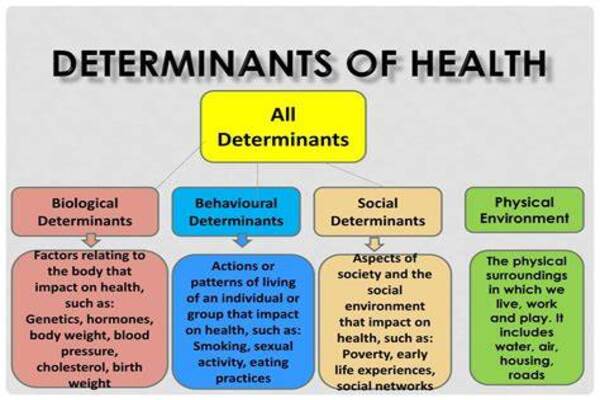

In unincorporated towns along the US-Mexico border, historically and socially marginalized groups become invisible to the healthcare system, demonstrating that geography serves as a structural determinant of health for low-income populations. So concluded a study by a team from the University of California, Riverside, that concentrated on the borderland of Southern California, notably the eastern Coachella valley.

From September to December 2020, Ann Cheney, an associate professor of social medicine, population, and public health in the School of Medicine, collaborated with María Pozar, a community investigator and CEO of Conchita Servicios de la Comunidad, to interview 36 Latinx and Indigenous Mexican caregivers of children with asthma or respiratory distress. The researchers discovered that populations in the “colonias” (unincorporated territories on the borders) lack essential necessary infrastructure, including healthcare access.

Nearly 2.7 million Hispanic or Latinx people live along the border between the United States and Mexico. The colonias’ immigrant population has poor English proficiency, health literacy, and income, as well as lower levels of formal education. Many are undocumented.

Our work shows the importance of geography in health and how geography acts as a structural determinant of health. For example, foreign-born caregivers who speak Spanish or Purépecha prefer to take their children across the U.S.-Mexico border for respiratory health care because physicians there provide them with a diagnosis and treatment plan that they perceive improves their children’s health.

Dr. Cheney

“Our work shows the importance of geography in health and how geography acts as a structural determinant of health,” Cheney said. “For example, foreign-born caregivers who speak Spanish or Purépecha prefer to take their children across the U.S.-Mexico border for respiratory health care because physicians there provide them with a diagnosis and treatment plan that they perceive improves their children’s health.”

The study, published in the journal Social Science & Medicine, found the caregivers perceive U.S.-based physicians as not providing them with sufficient information since most physicians do not speak their language and do not adequately listen to or are dismissive of their concerns about their children’s respiratory health. The caregivers perceive Mexican-based physicians as providing them with a diagnosis and treatment plan, whereas U.S.-based physicians often prescribe medications and provide no concrete diagnosis.

“Further, only those with legal documentation status can cross the border, which contributes to disparities in children’s respiratory health,” Cheney said. “Thus, caregivers without legal status in the U.S. must access healthcare services in the U.S. for their children and receive, what these caregivers perceive, as suboptimal care.”

Cheney added she was surprised to learn that caregivers who did not have legal documentation status in the U.S. asked trusted family and friends to take their children across the border to receive healthcare services for childhood asthma and related conditions.

“Geography, meaning living in unincorporated communities, harms health,” she said. “Geography and the politics of place determines who can and cannot cross borders.”

Study participants discussed the distance they needed to travel to pediatric specialty care for the care and management of their children’s respiratory health problems. Some commented on the lack of interaction and communication with physicians during medical visits. Some participants commented on the lack of physicians’ knowledge about the connections between their children’s exposure to environmental hazards and poor respiratory health and allergic symptoms.

The research took place in four unincorporated rural communities — Mecca, Oasis, Thermal, and North Shore — in eastern Coachella Valley, along the northern section of the Salton Sea. People living in the colonias here are subject to the health effects of environmental hazards. Many are farmworkers living and working in the nearby agricultural fields. Most of the workforce lives in mobile parks and below the federal poverty line.

“In addition to toxic water and dust from the Salton Sea, other environmental health hazards, such as agriculture pesticide exposure, waste processing facilities, and unauthorized waste dumps, also contribute to this community’s high incidence of poor respiratory health,” said Gabriela Ortiz, the first author of the research paper and a graduate student in anthropology who works with Cheney. “These communities are vulnerable to the policies and governing decisions around exposure to environmental hazards and infrastructure development. The absence of infrastructure and lack of healthcare infrastructure limits their access to primary care and specialty care services.”

Ortiz explained that anthropologists and social scientists have long argued that environmental injustices are a product of structural violence.

“This is indirect violence caused by social structures and institutions that prevent individuals from meeting their basic needs because of political economic domination and class-based exploitation,” she said. “Understanding the complex interplay between geography, borderlands, and health is essential for coming up with effective public health policy and interventions.”