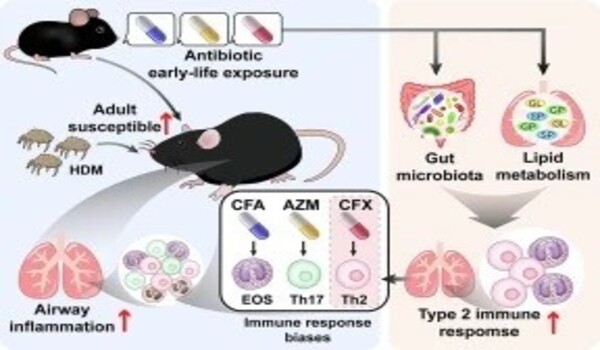

Researchers at the University of British Columbia have demonstrated for the first time how and why drugs can deplete bacteria in a newborn’s gut, resulting in lifelong respiratory allergies.

In a study published today in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, a research team from the School of Biomedical Engineering (SBME) found a unique chain of events that leads to allergies and asthma. In doing so, they have created numerous new pathways for investigating potential preventions and therapies.

“Our research finally shows how the gut bacteria and antibiotics shape a newborn’s immune system to make them more prone to allergies,” said senior author Dr. Kelly McNagny (he/him), professor in the SBME and the department of medical genetics. “When you see something like this, it really changes the way you think about chronic disease. This is a well-sculpted pathway that can have lasting consequences on susceptibility to chronic disease as an adult.”

We can now detect when a patient is on the verge of developing lifelong allergies, simply by the increase in ILC2s. And we can potentially target those cell types instead of relying on supplementation with butyrate, which only works early in life.

Ahmed Kabil

Allergies are caused by the immune system responding too strongly to harmless items such as pollen or pet dander, and they are the primary cause of emergency room visits in children. Normally, the immune system defends us against hazardous invaders such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites. In the case of allergies, it misidentifies something harmless as a threat — in this example, parasites — and initiates a response that causes symptoms such as sneezing, itching, or swelling.

Our immune system’s development begins very early in life. Microbes in the baby gut appear to play an important role, according to research conducted over the last two decades. Antibiotics are frequently administered to babies shortly after birth to fight illnesses, which can reduce the number of specific bacteria. Some of those bacteria produce a compound called butyrate, which is key to halting the processes uncovered in this research.

Dr. McNagny’s lab had previously shown that infants with fewer butyrate-producing bacteria become particularly susceptible to allergies. They had also shown that this could be mitigated or even reversed by providing butyrate as a supplement in early life. Now, by studying the process in mice, they have discovered how this works.

Mice with depleted gut bacteria who received no butyrate supplement developed twice as many of a certain type of immune cell called ILC2s. These cells, discovered less than 15 years ago, have quickly become prime suspects in allergy development. The researchers showed that ILC2s produce molecules that ‘flip a switch’ on white blood cells to make them produce an abundance of certain kinds of antibodies. These antibodies then coat cells as a defence against foreign invaders, giving the allergic person an immune system that is ready to attack at the slightest provocation.

Without butyrate to suppress them, the number of each cell, molecule, and antibody outlined in this cascade increases substantially. Butyrate must be administered within a narrow window after birth — a few months for humans, a few weeks for mice — in order to avoid ILC2 growth and subsequent events. If that opportunity is missed and ILC2s grow, the remaining steps are ensured and will stay with someone for the rest of their lives.

Now that researchers understand the additional phases, they have many more possible targets for stopping the cascade, even after the supplementing window has closed.

“We can now detect when a patient is on the verge of developing lifelong allergies, simply by the increase in ILC2s,” said Ahmed Kabil (he/him), the study’s first author and a PhD candidate in the SBME. “And we can potentially target those cell types instead of relying on supplementation with butyrate, which only works early in life.”

According to Dr. McNagny and study co-leader Dr. Michael Hughes, treating people’s allergies with antihistamines and inhalers just reduces symptoms, not curing the disease. To make more long-term progress, researchers must target the cells and systems that comprise this hypersensitive immune system. There had previously been no method to accomplish this selectively.

With this new understanding, patients can look forward to more effective, long-term therapies that target the underlying cause of the disease, opening the way for a future in which allergies are better managed, if not eliminated entirely.