Researchers study the profound changes that occur in the brain throughout pregnancy. Pregnancy is a transforming period in a person’s life during which the body undergoes rapid physiological adjustments in preparation for parenthood, as we all know. What the broad hormonal alterations caused by pregnancy do to the brain is still a mystery. Researchers in Professor Emily Jacobs’ group at UC Santa Barbara have created the first-ever map of a human brain during pregnancy, shedding insight on this understudied area.

“We wanted to look at the trajectory of brain changes specifically within the gestational window,” said Laura Pritschet, lead author of a paper published in Nature Neuroscience. Previous studies had taken snapshots of the brain before and after pregnancy, she said, but never have we witnessed the pregnant brain in the midst of this metamorphosis.

The researchers studied one first-time mother’s brain every few weeks, beginning before pregnancy and continuing for two years after childbirth. The results, gathered in partnership with Elizabeth Chrastil’s team at UC Irvine, show changes in the brain’s gray and white matter throughout gestation, implying that the brain is capable of remarkable adaptability well into adulthood.

Laura Pritschet and the study team were a tour de force, conducting a rigorous suite of analyses that generated new insights into the human brain and its incredible capacity for plasticity in adulthood.

Dr. Jacobs

Their precise imaging technique enabled them to capture ongoing brain reconfiguration in the subject in great detail. This approach builds on earlier research that studied women’s brains before and after birth. As the authors put it, “our goal was to fill the gap and understand the neurobiological changes that happen during pregnancy itself.”

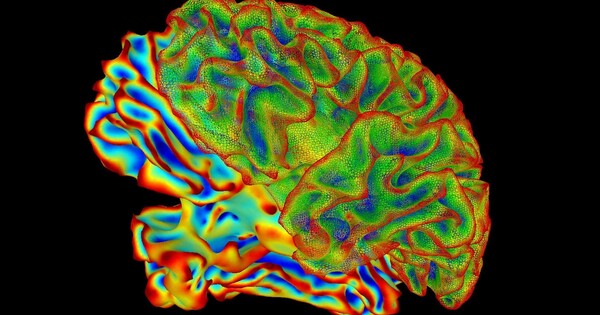

Decrease in gray matter, increase in white matter

The most noticeable alteration the scientists saw as they examined the subject’s brain over time was a drop in cortical gray matter volume, the wrinkled outer region of the brain. Gray matter volume decreased as hormone synthesis increased throughout pregnancy. The authors stressed that a decrease in gray matter volume is not always a bad thing. This alteration could imply a “fine-tuning” of brain circuits, similar to what all young people experience when they enter puberty and their brains become more specialized. Pregnancy most likely represents another stage of cortical refining.

“Laura Pritschet and the study team were a tour de force, conducting a rigorous suite of analyses that generated new insights into the human brain and its incredible capacity for plasticity in adulthood,” Jacobs said.

Less noticeable but equally significant, the researchers discovered large increases in white matter, which is located deeper in the brain and is responsible for improving communication between regions. While the decrease in gray matter lasted long after giving birth, the rise in white matter was only temporary, peaking in the second trimester and decreasing to pre-pregnancy levels around the time of birth. According to the researchers, this type of effect has never been documented before using before-and-after scans, providing for a more accurate estimate of how dynamic the brain can be in a relatively short amount of time.

“The maternal brain undergoes a choreographed change across gestation, and we are finally able to see it unfold,” Jacobs told me. These alterations indicate that the adult brain is capable of enduring extended periods of neuroplasticity, which may promote behavioral adaptations associated with parenting.

“Eighty-five percent of women experience pregnancy one or more times over their lifetime, and around 140 million women are pregnant every year,” said Pritschet, who seeks to “dispel the dogma” around women’s fragility during pregnancy. She emphasized that prenatal neuroscience should not be seen as a niche study area, because the findings from this line of inquiry will “deepen our overall understanding of the human brain, including its aging process.”

The open-access dataset, available online, serves as a jumping-off point for future studies to understand whether the magnitude or pace of these brain changes hold clues about a woman’s risk for postpartum depression, a neurological condition that affects roughly one in five women. “There are now FDA-approved treatments for postpartum depression,” Pritschet said, “but early detection remains elusive. The more we learn about the maternal brain, the better chance we’ll have to provide relief.”

That is exactly what the authors have set out to do. Through the Maternal Brain Project, their team is expanding on these early results with assistance from the Ann S. Bowers Women’s Brain Health Initiative, which is managed by Jacobs. More women and their partners are enrolling at UC Santa Barbara and UC Irvine, as well as through international collaboration with Spanish researchers.