According to a study presented at the 2019 NCRI Cancer Conference, men with greater levels of ‘free’ testosterone and a growth hormone in their blood are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer.

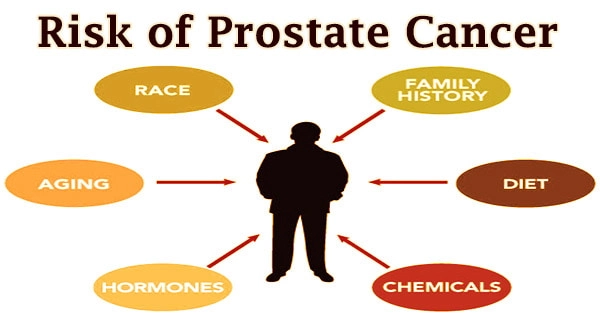

Other variables that raise a man’s chance of acquiring prostate cancer include his age, ethnicity, and a family history of the illness. North America, northern Europe, Australia, and Caribbean islands have the highest rates of prostate cancer. In Asia, Africa, Central America, and South America, it is less frequent.

The current study, which included almost 200,000 men, is one of the first to demonstrate significant evidence of two characteristics that may be altered to lower prostate cancer risk. Prostate cancer screening is likely to account for at least some of the variance in certain industrialized nations, but other factors such as lifestyle variations (diet, etc.) are also likely to play a role.

Prostate cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in men worldwide after lung cancer and a leading cause of cancer death. But there is no evidence-based advice that we can give to men to reduce their risk.

Dr. Ruth Travis

The research was led by Dr. Ruth Travis, an Associate Professor, and Ellie Watts, a Research Fellow, both based at the Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, UK. Dr. Travis said: “Prostate cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in men worldwide after lung cancer and a leading cause of cancer death. But there is no evidence-based advice that we can give to men to reduce their risk.”

“We were interested in studying the levels of two hormones circulating in the blood because previous research suggests they could be linked with prostate cancer and because these are factors that could potentially be altered in an attempt to reduce prostate cancer risk.”

The researchers looked at 200,452 males in the UK Biobank study. When they enrolled in the trial, they were all cancer-free and not on any hormone treatment. The guys provided blood samples to be analyzed for testosterone and an insulin-like growth factor-I-like growth hormone (IGF-I).

The researchers calculated the amount of free testosterone in the blood, which is testosterone that is not attached to any other molecule and so may have an effect on the body. To assist the researchers to account for normal changes in hormone levels, a subgroup of 9,000 men provided a second blood sample at a later date.

The men were tracked for an average of six to seven years to see if prostate cancer developed. There were 5,412 instances of the illness in the group, with 296 fatalities. Men with greater blood levels of the two hormones were more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer, according to the study.

Men were 9 percent more likely to develop prostate cancer for every rise of five nanomoles in IGF-I per liter of blood (5 nmol/L). Prostate cancer risk increased by 10% for every rise of 50 picomoles of ‘free’ testosterone per liter of blood (50 pmol/L).

In a population-wide analysis, the researchers found that men with the highest levels of IGF-I have a 25% higher risk of prostate cancer than those with the lowest levels. Men with the greatest levels of ‘free’ testosterone had an 18% higher risk of prostate cancer than those with the lowest levels.

Because the blood tests were performed several years before the prostate cancer appeared, the researchers believe that the hormone levels are causing the increased risk of prostate cancer, rather than the malignancies causing higher hormone levels. The researchers were also able to account for other characteristics that potentially impact cancer risk, such as body size, socioeconomic position, and diabetes, due to the study’s huge size.

Dr. Travis said: “This type of study can’t tell us why these factors are linked, but we know that testosterone plays a role in the normal growth and function of the prostate and that IGF-I has a role in stimulating the growth of cells in our bodies.”

“What this research does tell us is that these two hormones could be a mechanism that links things like diet, lifestyle, and body size with the risk of prostate cancer. This takes us a step closer to strategies for preventing the disease.”

Dr. Travis and Ms. Watts will continue to go at the data from this study to see if their conclusions are correct. They also want to focus on risk factors for the most aggressive kinds of prostate cancer in the future.

Men who are overweight or obese are more likely to acquire an aggressive type of prostate cancer in the future. Obese men’s recovery following surgery is longer and more difficult, and their chance of dying from prostate cancer is greater, according to research.

Professor Hashim Ahmed, chair of NCRI’s prostate group and Professor of Urology at Imperial College London, who was not involved in the research said:

“These results are important because they show that there are at least some factors that influence prostate cancer risk that can potentially be altered. In the longer term, it could mean that we can give men better advice on how to take steps to reduce their own risk.”

This study also emphasizes the necessity of large-scale research, which is only feasible because of the hundreds of men who volunteered to participate.