According to new research, exposure to dangerous levels of heat and humidity in cities around the world has increased dramatically over the last three decades. The number of people exposed to extremely hot and humid days in a given year (measured in “person-days”) tripled between 1983 and 2016, according to a study of over 13,000 cities.

It’s the result of two trends colliding: increasing urban population and rising global average temperatures. Because cities are typically designed to trap heat, they frequently reach higher temperatures than surrounding rural areas. As a result, when people flock to cities, they are also flocking to places where they may be more vulnerable to heat-related illness and death. To make matters worse, extreme heat is already a leading weather-related killer, and climate change is exacerbating the problem.

Cities, the authors argue, will need to find ways to stay cool in a warming world in order to better protect their residents. “Long-term adaptation is frankly bleak in some cities.” But for much of the planet, we can use existing tools,” says Cascade Tuholske, a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University and lead author of the study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “I don’t see population growth and urbanization as a problem. It’s due to a lack of preparation.”

Our research is retrospective for billions of people on the planet. Every day, this is their lived experience. We must learn from them and collaborate with people in extremely hot cities to adapt.

Cascade Tuholske

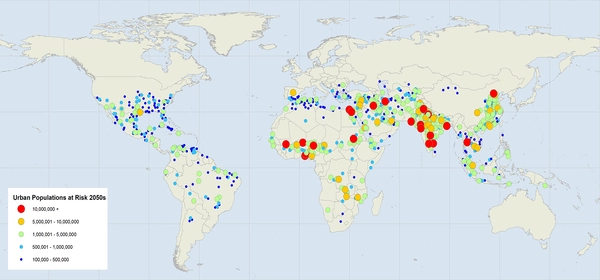

Tuholske and his colleagues discovered that a quarter of the world’s population lives in areas where exposure to extreme heat and humidity is increasing. They defined “extreme” in the study as at least 30 degrees Celsius on the wet-bulb globe temperature scale. The wet-bulb globe scale provides a detailed assessment of temperature, humidity, wind speed, cloud cover, and sun angle. On that scale, thirty degrees is equivalent to a day that feels like 106 degrees Fahrenheit. (This isn’t a direct conversion from Celsius to Fahrenheit because other factors are taken into account.)

They relied on both infrared satellite imagery and on-the-ground readings to determine weather conditions over roughly the last three decades. Using population data gathered by the European Commission and Columbia’s Center for International Earth Science Information Network, the researchers multiplied the number of extremely hot days by the number of people in each city to get a total of “person-days” in which city-dwellers experienced those extreme conditions. The number of person-days grew from 40 billion per year in 1983 to 119 billion in 2016 — showing how many more people are now suffering through extremely hot weather in the world’s cities.

According to the study’s authors, rising temperatures are responsible for roughly one-third of the global increase in exposure. The majority of the increase in exposure is due to more people moving to cities. However, this ratio varies from city to city. The main cause of heat exposure in Delhi, India, was a surge in population growth. However, climate change was a slightly larger factor in Kolkata. The differences indicate that solutions will most likely need to be tailored to each city. As cities continue to attract new residents and global average temperatures rise, they will need to act quickly.

Because of a process known as the Urban Heat Island Effect, cities can reach temperatures that are several degrees hotter than surrounding areas. Heat is absorbed by asphalt and other dark surfaces. More heat is released by factory exhaust and tailpipes. And there are fewer trees or plants to provide shade or the cooling effect of evapotranspiration (a process similar to how humans cool down by sweating). These effects are exacerbated in neighborhoods that have received less investment and more industrial activity over time, a phenomenon that has been shown in other studies to disproportionately harm communities of color in the United States.

Despite the increasing danger, heat-related deaths are largely avoidable. Cities can cool down by painting rooftops and other surfaces white to reflect heat. Increasing the amount of trees and greenery in neighborhoods also helps. There’s also more that can be done to warn people about impending heatwaves so they can find public cooling centers or other places to cool off with air conditioning. New York City and Los Angeles are just two of the major metropolitan areas working to achieve this goal around the world.

“Our research is retrospective for billions of people on the planet.” Every day, this is their lived experience,” Tuholske says. “We must learn from them and collaborate with people in extremely hot cities to adapt.”