Definition: Copper, an essential mineral, is naturally present in some foods and is available as a dietary supplement. It is a cofactor for several enzymes (known as “cuproenzymes”) involved in energy production, iron metabolism, neuropeptide activation, connective tissue synthesis, and neurotransmitter synthesis. In humans, copper is essential to the proper functioning of organs and metabolic processes. The human body has complex homeostatic mechanisms which attempt to ensure a constant supply of available copper while eliminating excess copper whenever this occurs.

However, like all essential elements and nutrients, too much or too little nutritional ingestion of copper can result in a corresponding condition of copper excess or deficiency in the body, each of which has its own unique set of adverse health effects.

Copper also helps the body form collagen and absorb iron, and plays a role in energy production. Most copper in the body is found in the liver, brain, heart, kidneys, and skeletal muscle. Both too much and too little copper can affect how the brain works. Impairments have been linked to Menkes, Wilson’s, and Alzheimer’s disease. Deficiency is rare, but it can lead to cardiovascular disease and other problems.

A wide variety of plant and animal foods contain copper, and the average human diet provides approximately 1,400 mcg/day for men and 1,100 mcg/day for women that is primarily absorbed in the upper small intestine. Almost two-thirds of the body’s copper is located in the skeleton and muscle. Only small amounts of copper are typically stored in the body, and the average adult has a total body content of 50–120 mg copper.

Copper is found in a wide variety of foods.

Good sources include:

- oysters and other shellfish

- whole grains

- beans

- potatoes

- yeast

- dark leafy greens

- cocoa

- dried fruits

- black pepper

- organ meats, such as kidneys and liver

- nuts, such as cashews and almonds

Most fruits and vegetables are low in copper, but it is present in whole-grains, and it is added to some breakfast cereals and other fortified foods.

Supplements – Copper supplements can prevent copper deficiency, but supplements should be taken only under a doctor’s supervision. Different forms of copper supplementation have different absorption rates. For example, the absorption of copper from cupric oxide supplements is lower than that from copper gluconate, sulfate, or carbonate. Supplementation is generally not recommended for healthy adults who consume a well-balanced diet which includes a wide range of foods. Many popular vitamin supplements (contain 2 mg) include copper as small inorganic molecules such as cupric oxide. These supplements can result in excess free copper in the brain as the copper can cross the blood-brain barrier directly. Normally, organic copper in food is first processed by the liver which keeps free copper levels under control.

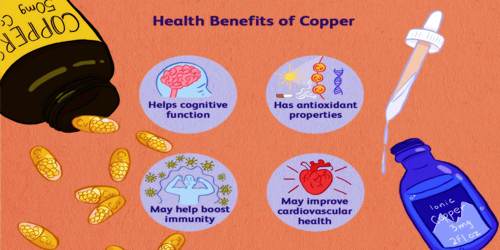

Health Benefits of Copper: Copper is an essential trace element (i.e., micronutrient) that is required for plant, animal, and human health. It is also required for the normal functioning of aerobic (oxygen-requiring) microorganisms. Together with iron, it enables the body to form red blood cells. It helps maintain healthy bones, blood vessels, nerves, and immune function, and it contributes to iron absorption. Sufficient copper in the diet may help prevent cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis, too.

Cardiovascular Health – Low copper levels have been linked to high cholesterol and high blood pressure. One group of researchers has suggested that some patients with heart failure may benefit from copper supplements. Animal studies have linked low copper levels to CVD, but it remains unclear if a deficiency would have the same impact on humans.

Neuron Signaling – In 2016, Prof. Chris Chang, a chemist who is part of the Sackler Sabbatical Exchange Program at Berkeley, CA, devised and used a fluorescent probe to track the movement of copper in and out of nerve cells.

Prof. Chang says: “Copper is like a brake or dimmer switch, one for each nerve cell.” His team found that, if high amounts of copper enter a cell, this appears to reduce neuron signaling. When copper levels in that cell fall, signaling resumes.

Immune Function – Too little copper can lead to neutropenia. This is a deficiency of white blood cells, or neutrophils, which fight off infection. A person with a low level of neutrophils is more likely to get an infectious disease.

Osteoporosis – Severe copper deficiency is associated with lower bone mineral density and a higher risk of osteoporosis. More research is needed on how marginal copper deficiency may affect bone health, and how copper supplementation might help prevent and manage osteoporosis.

Collagen Production – Copper plays an important role in maintaining collagen and elastin, major structural components of our bodies. Scientists have hypothesized that copper may have antioxidant properties, and that, together with other antioxidants, a healthful intake may help prevent skin aging. Without sufficient copper, the body cannot replace damaged connective tissue or the collagen that makes up the scaffolding for bone. This can lead to a range of problems, including joint dysfunction, as bodily tissues begin to break down.

Arthritis – Animal studies have indicated that copper may help prevent or delay arthritis, and people wear copper bracelets for this purpose. However, no human studies have confirmed this.

Antioxidant Action – Copper may also have an antioxidant function. It may help reduce the production of free radicals. Free radicals can damage cells and DNA, leading to cancer and other diseases.

Since copper availability in the body is hindered by an excess of iron and zinc intake, pregnant women prescribed iron supplements to treat anemia or zinc supplements to treat colds should consult physicians to be sure that the prenatal supplements they may be taking also have nutritionally-significant amounts of copper. When newborn babies are breastfed, the babies’ livers and the mothers’ breast milk provide sufficient quantities of copper for the first 4–6 months of life. When babies are weaned, a balanced diet should provide adequate sources of copper. Cow’s milk and some older infant formulas are depleted in copper.

Advice – The recommended daily allowance (RDA) is around 900 micrograms (mcg) a day for adolescents and adults. The upper limit for adults aged 19 years and above is 10,000 mcg, or 10 milligrams (mg) a day. An intake above this level could be toxic.

Deficiency and Risks of Copper: Copper deficiency is uncommon in humans. Based on studies in animals and humans, the effects of copper deficiency include anemia, hypopigmentation, hypercholesterolemia, connective tissue disorders, osteoporosis, and other bone defects, abnormal lipid metabolism, ataxia, and increased risk of infection. A high intake of zinc (150 mg a day or above) and vitamin C (over 1,500 mg a day) may induce copper deficiency by competing with copper for absorption in the intestine.

Copper deficiency has been seen in infants who consume cow’s milk instead of formula. Cow’s milk has a low copper content. Children under 1 year should be ideally breast fed and if not, fed manufactured formula. Cow’s milk does not have the required nutrients for a human infant.

Menkes Disease – Menkes disease is a rare, X-linked, recessive disorder of copper homeostasis caused by ATP7A mutations, which encode a copper-transporting ATPase. In these individuals, intestinal absorption of dietary copper drops sharply, leading to signs of copper deficiency, including low serum copper and CP levels. The typical manifestations of Menkes disease include failure to thrive, impaired cognitive development, aortic aneurysms, seizures, and unusually kinky hair. Most individuals with Menkes disease die by age 3 years if untreated, but subcutaneous injections of copper starting in the first few weeks after birth can reduce mortality risk and improve development.

Low levels of copper can lead to:

- anemia

- low body temperature

- bone fractures

- osteoporosis

- loss of skin pigmentation

- thyroid problems

Metabolic diseases can affect the way the body absorbs vitamins and minerals.

Celiac Disease – In a study of 200 adults and children with celiac disease, of which 69.9% claimed to maintain a gluten-free diet, 15% had copper deficiency (less than 70 mcg/dL in serum in men and girls younger than 12 years and less than 80 mcg/dL in women older than 12 years and/or CP less than 170 mg/L) as a result of intestinal malabsorption resulting from the intestinal lining alterations associated with celiac disease. In its 2009 clinical guidelines for celiac disease, the American College of Gastroenterology notes that people with celiac disease appear to have an increased risk of copper deficiency and that copper levels normalize within a month of adequate copper supplementation while eating a gluten-free diet.

The brain and the nervous system – Too little or too much copper can damage brain tissue. In adults, neurodegeneration has been observed as a result of a copper imbalance. This may be due to a problem with the mechanisms involved in metabolizing copper for use in the brain. High levels of copper can lead to oxidative damage in the brain. In Wilson’s disease, for example, high levels of copper collect in the liver, brain, and other vital organs.

Alzheimer’s Disease – An excessive accumulation of copper has also been associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Prof. Chang and colleagues have hypothesized that when copper accumulates in unusual ways, this may cause amyloid plaques to build up on a nerve cell. A buildup of amyloid plaques can lead to Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Taking High Doses of Zinc Supplements – High dietary intakes of zinc can interfere with copper absorption, and excessive use of zinc supplements can lead to copper deficiency. Reductions in erythrocyte copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, a marker of copper status, have been reported with even moderately high zinc intakes of approximately 60 mg/day for up to 10 weeks. People who regularly consume high doses of zinc from supplements or use excessive amounts of zinc-containing denture creams can develop copper deficiency because zinc can inhibit copper absorption. This is one reason the FNB established the UL for zinc at 40 mg/day for adults.

Other diseases in which abnormalities in copper metabolism appear to be involved include Indian childhood cirrhosis (ICC), endemic Tyrolean copper toxicosis (ETIC), and idiopathic copper toxicosis (ICT), also known as non-Indian childhood cirrhosis. ICT is a genetic disease recognized in the early twentieth century primarily in the Tyrolean region of Austria and in the Pune region of India. ICC, ICT, and ETIC are infancy syndromes that are similar in their apparent etiology and presentation. Both appear to have a genetic component and a contribution from elevated copper intake.

Taking high doses of copper could cause:

- stomach pain

- sickness

- diarrhoea

- damage to the liver and kidneys (if taken for a long time)

If any people take copper supplements, don’t take too much as this could be harmful. Having 1mg or less a day of copper supplements is unlikely to cause any harm.

Information Sources: