“Ħaġar Qim” (Maltese pronunciation: [ħadʒar ˈʔiːm]; “Standing/Worshipping Stones”), is a megalithic temple complex, which is located on the southwest coast on the Mediterranean island of Malta, and it was built between 3500 BC and 2900 BC. The Megalithic Temples of Malta are among the most ancient religious sites on Earth, described by the World Heritage Sites committee as “unique architectural masterpieces.”

“Ħaġar Qim” stands on a hilltop overlooking the sea and the islet of Fifla, not more than 2km south-west of the village of Qrendi. At the bottom of the hill, only 500m away, one finds the remarkable temples of Mnajdra. In 1992 UNESCO recognized Ħaġar Qim and four other Maltese megalithic structures as World Heritage Sites.

Although Ħaġar Qim was first excavated in 1839, the temple complex itself had never really been completely buried. This is due to the fact that the tallest stones of the temple remained exposed above the ground over the millennia, and are even said to have been featured in 18th and 19th-century paintings. Ħaġar Qim’s builders used globigerina limestone in the temple’s construction. As a result of this, the temple has suffered from severe weathering and surface flaking over the millennia. In 2009 work was completed on a protective tent.

The biggest of the stones for this mysterious monument (Ħaġar Qim) are 7 by 3 meters and weighs over 20 tons. Parts of the temple line up with the summer solstice’s sunrise and sunset and there is a theory that this and other Maltese structures may be even older than believed.

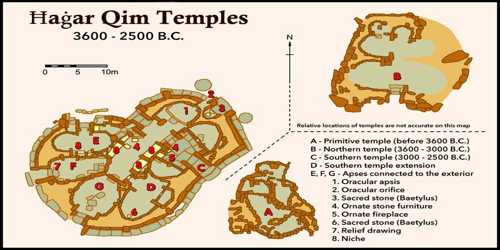

(Map of “Ħaġar Qim” Temples)

The ‘Hagar Qim’ (‘Worshipping Stones’) temple complex consists of a central building and the remains of at least two other structures. It has been pointed out that unlike most other Neolithic Maltese temple complexes, the ‘Hagar Qim’ temple complex consists of only one, instead of the more common two or three temples. Nevertheless, its design is similar to these other Neolithic temples. This design consists of a large forecourt and a monumental façade.

The Ħaġar Qim façade contains the largest stone used in Maltese megalithic architecture, weighing 57 tons. The upright menhir stands 5.2 m (17 ft) high. Erosion has affected the outer southern wall where the orthostats are exposed to sea-winds. Over the millennia, the temple has suffered severe weathering and surface flaking. The ‘Hagar Qim’ temple complex is made up of a series of C-shaped rooms known as apses. These apses are arranged on each side of a central paved space. Walls and slabs with square portholes cut through as doorways were used to screen off the apses. It has been noted this practice is unusual, as the apses of other similar temples have not been so well screened off.

One of the prehistoric chambers at Ħaġar Qim holds an elliptical hole which is hewn out in alignment with the Summer Solstice sunrise. At sunrise, on the first day of summer, the sun’s rays pass through this hole and illuminate a stone slab inside the chamber. Beyond the temple entrance is an oval area 14.3 m (47 ft) long and 5.5 m (18 ft) wide with large slab walls, originally topped by courses of masonry. The two apsidal ends are separated from the central court by two vertical slabs pierced by rectangular openings. These openings are thought to have been adorned with curtains to limit access to the side apses.

(Ħaġar Qim Temples, Malta)

The central area is paved with well-set smooth blocks, and along the walls are low stone altars, originally decorated with pit-marks. Some of these blocks are discolored by fire. In 1839, archaeologists discovered important objects in this court, now shown in the Valletta Museum. These include stone statuettes, a detailed altar-stone with deep carvings representing vegetation, a stone slab with spirals in relief and a displaced sill-stone. The right-hand apse once held a pen, theoretically intended for the corralling of animals. The left-hand apse has a high trilithon altar on its left, two others on right with one in a smaller chamber. An additional chamber beyond it combines a central court, niche and right apse.

Although this modern structure is useful in reducing the erosion caused by the exposure of the temple to the elements, it would no doubt have an effect on the aesthetic value of the site and the landscape as a whole. Perhaps this is one of the dilemmas of the conservators whether to preserve the site by adding a structure that would affect its aesthetic value, or to leave the site in its natural condition and risk losing it eventually.

Information Sources: