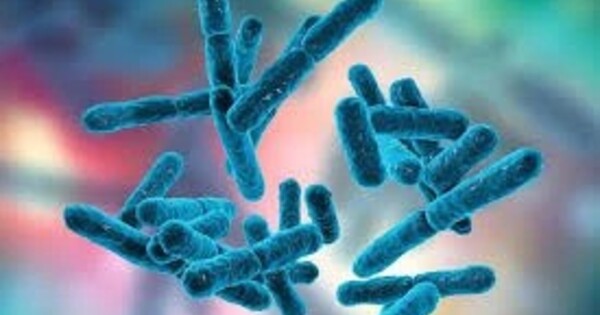

Researchers at Japan’s RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences, led by Hiroshi Ohno, have established a relationship between gut flora and the efficacy of milk allergy oral immunotherapy. The study, published in the professional journal Allergology International, discovered that Bifidobacterium – a genus of beneficial bacteria found in the gut – was connected with a higher risk of treatment success. The discovery could aid in the creation of more effective oral immunotherapies, potentially by combining them with probiotic supplements.

Many youngsters are allergic to cow’s milk, particularly certain milk proteins. Although most people outgrow it, for some, avoiding all milk-containing foods becomes a lifelong issue, especially when the allergic responses are severe and include anaphylactic shock. Researchers discovered that oral immunotherapy, a procedure in which patients consume little amounts of milk on purpose, improves milk allergy. Unfortunately, while allergic responses are minimized during treatment, tolerance typically fades quickly once treatment ends.

Gut bacteria are thought to help reduce allergic reactions to some foods, but little is known about the link between these bacteria and oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. Therefore, the RIKEN IMS team examined 32 children with cow’s milk allergy who received oral immunotherapy, with the first month being conducted in a hospital. “Oral immunotherapy is not without risk,” explains Ohno. “We closely monitored the children in the hospital, and in fact 4 children had such severe reactions to the milk that we could not allow them to continue the treatment.”

With this study, we have identified gut environmental factors that help establish immune tolerance against cow’s milk allergy via oral immunotherapy. The next step is to examine the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and to develop ways to improve the effectiveness of oral immunotherapy, such as the addition of probiotic supplements.

Hiroshi Ohno

The remaining 28 children underwent an additional 12 months of home treatment. They then avoided milk for two weeks before being tested on a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge to see if they could still handle it without experiencing any adverse reactions. During the food challenge, children were given a small amount of placebo or milk (0.01 ml), which was gradually increased every 20 minutes until they developed an allergic reaction or could drink the final 30 ml without reacting.

The researchers focused their analyses on immunological and bacterial changes during the treatment and the relationship between gut bacteria and successful treatment — which was defined as showing milk tolerance that lasted beyond the treatment period by passing the food challenge. They found that during treatment, immunological markers for cow’s milk allergy improved, and bacteria in the gut changed. Nevertheless, after two weeks of avoiding milk, only 7 of the 28 children passed the food challenge, even though they had been able to drink milk safely at the end of the treatment.

To figure out why the medication worked for these seven children but not the others, the researchers examined for clinical variables and gut bacteria types associated with successful treatment. In terms of clinical considerations, failure therapy was more frequent in children treated for eczema or asthma, as well as children with greater levels of milk-protein antibodies at the start. The presence of Bifidobacterium, a genus of beneficial bacteria in the Bifidobacteriaceae family, was associated with a higher chance of treatment success.

In fact, only children who passed the final food challenge showed an increasing trend in these bacteria over the course of treatment. When considering ways to improve oral immunotherapy, this is good news because while the first two factors are difficult to change, the types of bacteria in one’s gut are not set in stone.

“With this study, we have identified gut environmental factors that help establish immune tolerance against cow’s milk allergy via oral immunotherapy,” says Ohno. “The next step is to examine the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and to develop ways to improve the effectiveness of oral immunotherapy, such as the addition of probiotic supplements.”