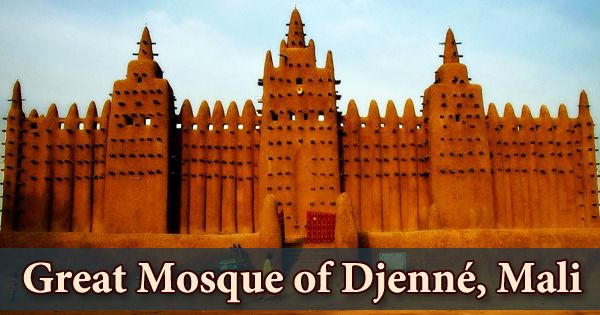

The Great Mosque of Djenné (French: Grande mosquée de Djenné, Arabic: الجامع الكبير في جينيه), in present-day Mali, is one of Africa’s wonders and one of the world’s most remarkable religious buildings. It is also the finest achievement of Sudano-Sahelian architecture (Sudano-Sahelian refers to the Sudanian and Sahel grassland of West Africa). The mosque is located in the flood plain of the Bani River in Djenné, Mali. It is the world’s largest mud-brick or adobe structure, and many architects believe it to be the pinnacle of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style, which has distinct Islamic influences. The site’s original mosque originates from the 13th century, although the current structure was completed in 1907. It is not just the heart of the Djenné community, but also one of Africa’s most famous sites. In 1988, UNESCO listed it as a World Heritage Site, along with the “Old Towns of Djenné.”

Djenné prospered as a significant center of business, learning, and Islam, which had been practiced since the beginning of the 13th century. It was founded between 800 and 1250 C.E. The exact year the original mosque in Djenné was built is uncertain, but it has been suggested that it was built between 1200 and 1330. Al-Sadi’s Tarikh al-Sudan, which chronicles the early history, possibly from oral tradition as it existed in the mid-seventeenth century, is the first text to mention the mosque. It’s the world’s largest mud-brick edifice, about 20 meters high and 91 meters long, and the best example of Sudano-Sahelian architecture, which is distinguished by adobe plastering and timber scaffolding.

There is no further documented record of the Great Mosque until René Caillié, a French adventurer, visited Djenné in 1828, years after it had been abandoned and wrote about it,

“In Jenné is a mosque built of earth, surmounted by two massive but not high towers; it is rudely constructed, though very large. It is abandoned to thousands of swallows, which build their nests in it. These occasions a very disagreeable smell, to avoid which, the custom of saying prayers in a small outer court has become common.”

The Great Mosque has become the spiritual and cultural heart of Mali, as well as the Djenné population, over the years. It also hosts the Crepissage de la Grande Mosquée (Plastering of the Great Mosque), a one-of-a-kind annual festival. Seku Amadu erected a new mosque on the site of the ancient palace between 1834 and 1836, to the east of the present mosque. The new mosque was a huge, low structure with no towers or decorations. In April 1893, French forces commanded by Louis Archinard conquered Djenné. Félix Dubois, a French journalist, visited the village soon after and described the remnants of the ancient mosque. The inside of the damaged mosque was being used as a graveyard at the time of his visit.

According to the tarikh, Sultan Kunburu converted to Islam and had his palace demolished and the place rebuilt into a mosque. The cultural property “Old Towns of Djenné” is a serial property that includes four archaeological sites: Djenné-Djeno, Hambarkétolo, Kaniana, and Tonomba, as well as the old fabric of Djenné’s current town, which spans 48.5 acres and is organized into ten districts. The property is part of a larger ensemble that has long represented a typical African city. It also serves as a good example of Islamic architecture in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In 1906, the town’s French administration arranged for the original mosque to be reconstructed with the construction of a school on the site of Seku Amadu’s mosque. Under the guidance of Ismaila Traoré, head of Djenné’s guild of masons, the renovation was finished in 1907. According to folklore, the original Great Mosque was built in the 13th century, when King Koi Konboro Djenné’s twenty-sixth ruler and first Muslim sultan (king) decided to establish a place of Muslim prayer in town using local materials and traditional design skills.

The mosque was enclosed by a wall and two towers were erected by King Konboro’s successors and the town’s rulers. The mosque compound grew over the ages, and by the 16th century, it was said that the mosque’s galleries could hold half of Djenné’s inhabitants. In his report of a trip across Mali in 1931, French ethnologist Michel Leiris claims that the new mosque was built by Europeans. He further claims that residents were so dissatisfied with the new structure that they refused to clean it until they were threatened with prison.

Even on the hottest days, the Great Mosque remains cool. The roof and walls are supported by a lattice of 90 internal wooden columns, which provide insulation from the sun’s heat. Meanwhile, the roof includes many apertures that enable fresh air to circulate during the dry season but maybe closed with terracotta covers during the rainy season. The prayer hall inside the mosque can accommodate up to 3,000 people. Two tombs can be found on the terrace in front of the eastern wall. The remains of Almany Ismala, an important 18th-century imam, are housed in the larger tomb to the south. A pond on the eastern side of the mosque was filled with earth to create the open area that is presently used for the weekly market during the French colonial period.

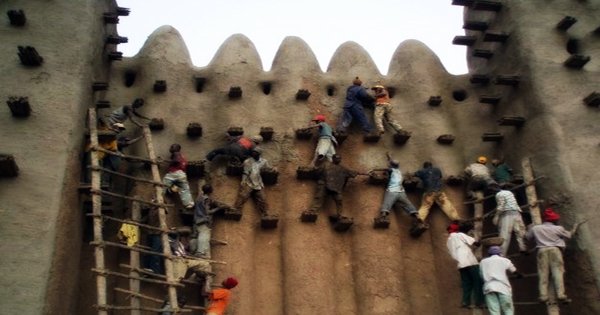

The current Great Mosque has a rectilinear plan and is partially encased by an outside wall. The structure is covered in an earthen roof and supported by gigantic pillars. The building’s walls are adorned with toron, which are bundles of rodier palm (Borassus aethiopum) sticks that protrude about 60 cm (2.0 ft) above the surface. The toron can also be used as ready-made scaffolding for annual maintenance. Half-pipes made of a ceramic stretch from the roofline and deflect rainwater away from the walls.

The mosque is built on a platform measuring about 75 m × 75 m (246 ft × 246 ft) that is raised by 3 meters (9.8 feet) above the level of the marketplace. The roof features many holes (above) with terra-cotta covers that offer fresh air to the inner rooms even on the hottest days. Three minarets and a succession of engaged columns make up the Great Mosque’s façade, which creates a rhythmic impression (below). When the Bani River floods, the platform protects the mosque. Six flights of stairs, each with pinnacles, lead up to it. The main entrance is located on the building’s northern side. The Great Mosque’s outside walls are not perfectly orthogonal to one another, resulting in a trapezoidal shape to the building’s layout.

Each April, in an epic one-day ceremony known as the Crépissage, the walls of Djenné’s Great Mosque are restored using mud (Plastering). The structure, like the town’s typical adobe homes, requires annual strengthening before Mali’s brief but devastating rainy season, which falls largely in July and August and brings nearly all of the country’s normal 1,000mm annual rainfall. Despite modest changes in shape each year, this massive operation ensures that the mosque will survive the rainy season. The Great Mosque’s prayer wall, or qibla, faces east towards Mecca and overlooks the main marketplace. Three huge, box-like towers or minarets projecting out from the main wall dominate the qibla. The central tower is approximately 16 meters tall.

Djenné’s residents have weathered numerous attempts over the years to change the character of their unique mosque and the essence of their yearly festival. The prayer hall, which measures roughly 26 by 50 meters (85 by 164 feet), is located behind the qibla wall in the eastern section of the mosque. The Rodier-palm roof is supported by nine inner walls that run north-south and are perforated by pointed arches that almost reach the roof. The Crépissage is a festival that celebrates Djenné’s community, faith, and tradition, as well as a crucial act of maintenance to keep the mosque’s walls from cracking and falling.

The interior courtyard to the west of the prayer hall, measuring 20 m × 46 m (66 ft × 151 ft), is surrounded on three sides by galleries. Arched apertures punctuate the walls of the galleries facing the courtyard. Women only have access to the western gallery. The establishment of a management committee for the Mosque, an association for Koranic schools, and monitoring by the village chief, its Council, and district chiefs provide customary protection for the Great Mosque, the Koranic schools, and the Tombs of the Saints.

Djenné’s community has worked tirelessly to preserve its cultural legacy and the Great Mosque’s unique identity. The peculiar architecture of Djenné renders it extremely vulnerable to environmental concerns, particularly flooding. Djenné is characterized by “exceptional architecture and its urban framework, of unusual harmony,” according to UNESCO, and the Great Mosque exemplifies this. Despite its centuries-long history, the mosque continues to play an important role in modern culture.

Information Sources: