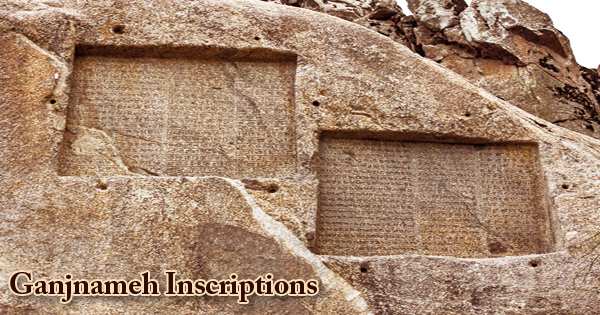

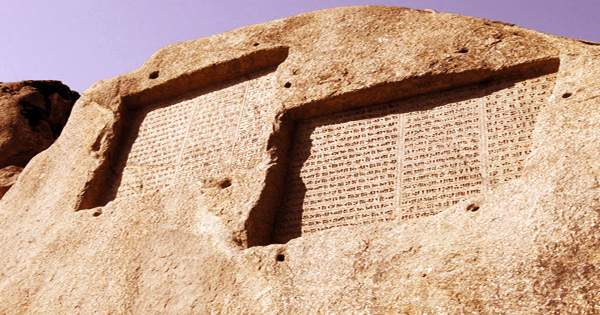

Ganjnameh (Persian: گنجنامه, romanized: Ganjnāme, Literally: Treasure Book) is so named because it was once believed that its cuneiform rock carvings were mysterious clues leading to caches of Median treasure. It is situated in western Iran, 12 km southwest of Hamadan (ancient Ecbatana), at an altitude of c. 2000 meters all the way across Mount Alvand. Two trilingual Achaemenid cuneiform inscriptions are housed at the site.

At the end of one of the hillsides of Alvand Mountain, which is a memory of the Achaemenid Empire, lies a significant ancient reminiscence of Persia. On a giant piece of granite, the two crucial inscriptions of this period are engraved there. The French painter and archaeologist, Eugene Flandin, who was accompanied by Pascal Coste, first studied them in-depth. Following their work, a British explorer, Sir Henry Rawlinson, used the inscriptions as a sort of Rosetta stone to decode the era’s cuneiform characters.

(Ganjnameh Inscriptions)

This place was on the road to Babel from Hegmataneh Hill (the summer capital of the Achaemenid Empire). It was one of the busiest and most safe paths of the time, therefore. About 500 BC, King Darius the Great ordered one of the inscriptions to be engraved. Khashayarsha (King Xerxes) ordered the second inscription to be built right next to the first, at the behest of his dead father. Their goal was to worship and pass their own thoughts and beliefs to Ahuramazda (the Zoroastrian God) and the honor of their ancestors.

On the order of Achaemenid King Darius the Great (r. 522-486 BC) and the one on the right by his son, King Xerxes the Great (r. 486-465 BC), the inscription on the upper left was formed. The texts are, in reality, a hubris-laden suck-up from the Achaemenid ruler Xerxes (r 486-465 BC) to the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda for making him such a stellar king. The message is repeated in three languages (Old Persian, Elamite, and Neo-Babylonian) on rock faces some 2 m high, to emphasize the point. A second panel commemorates his father, Darius, in a similar way. It is awesome to realize that in the long run, the many holes next to these inscriptions were intended to protect them from natural elements such as rain, storm, and sunshine. On two rocks on the other side of the town, the English and Persian translations of these inscriptions are engraved. These inscriptions were registered in 1931 on Iran’s national heritage list.

The two Ganjnameh inscription panels, sculpted in stone in 20 lines on a granite rock over a creek, measure 2 × 3 m each. The contents of the two inscriptions are similar, written in Old Persian, Neo-Babylonian and Neo-Elamite, except for the distinct royal name; Ahura Mazda receives praise, and lines and conquests are mentioned. Just to the east is the rock on which the inscriptions are engraved. The inscription on the left is named after King Darius the Great, and the inscription on the right is named after Khashayarsha. Every inscription is written in Persian, New Babeli, and Elami, each in three languages.

The translation of the two inscriptions is as follows:

- King Darius the Great’s inscription: “A Great God is Ahuramazda, the greatest of the gods, who created this earth, who created yonder sky, who created man, for man, who made King Darius, one king of many, one lord of many, I am Darius, the great King, the King of kings, King of countries containing all kinds of men, King in this great earth, far and wide, son of King Vishtasb, an Achaemenian.”

- The right inscription, belonging to King Xerxes I, reads: “The Great God is Ahuramazda, greatest of all the gods, who created the earth and the sky and the people; who made Xerxes king, and outstanding king as an outstanding ruler among innumerable rulers; I am the great king Xerxes, king of kings, king of lands with numerous inhabitants, king of this vast kingdom with far-away territories, son of the Achaemenid monarch Darius.”

The distinction is only in the names of the kings between the two documents. According to Stuart C. Brown, this mountain was apparently the main “east-west pass” through Mount Alvand in the pre-Hellenistic period. Ecbatana functioned as the summer capital during the Achaemenid era due to its high elevation and nice weather. So far, many titles have been named after these two inscriptions. The names used recently, however, are Jangnameh and Ganjnameh. They are given the name Jangnameh (Jang = War) under the influence of tales and people’s thoughts about the warfare of their kings. On the other hand, these inscriptions are given the name Ganjnameh (Ganj = Treasure) since the majority of people used to assume that these words contain a secret of a hidden treasure.

(Ganjnameh Waterfall)

Ganjnameh Waterfall: One of the province’s most significant waterfalls, near the city of Hamadan and at the tail end of the Abbas Abad Valley recreational park, is the Ganjnameh waterfall. From a height of around 12 m, this waterfall flows down; and it is known as Abbas Abad’s bath. Its average capacity is 200 liters/second. This waterfall is in the vicinity of the inscriptions of Ganjnameh and is also en route to the path from where the heights of the mountains of Alvand are available. The waterfall of Ganjnameh is a four-season waterfall, whose waterfalls from a height of 12 meters and creates a magnificent picture. In 2008, this waterfall was registered on the list of National Heritage Sites.

Information Sources: