Researchers discovered ancient living communities in the fossil record and monitored how their numbers fluctuated through each of the planet’s catastrophic extinctions using an algorithm similar to what Facebook employs to create friend choices.

During mass extinction events, the number of communities (a group of diverse species living in the same broad area) decreased, as expected. However, the rate at which communities vanished did not necessarily correspond to the overall loss of life and biodiversity during an extinction, implying that the ecological consequences of extinction are not always proportional to the number of species that perish.

“There have been times in our history where there have been major events that saw tremendous changes in communities, but very few species disappeared,” said lead author Drew Muscente, who conducted the study when he was a postdoctoral researcher at The University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences. “And there have been events where many species had disappeared and communities and ecosystems were barely affected at all.”

Muscente is now a Cornell College assistant professor. The research was published in the journal Geology recently. The findings highlight the necessity of studying communities in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of environmental change in the past and present.

“We try to understand how changes in these communities lead to the fundamental transformation of entire ecosystems,” said co-author Rowan Martindale, an associate professor at the Jackson School.

It is notoriously difficult to identify communities in the fossil record. The majority of paleocommunity study focuses on comparing fossil samples and collections collected from rocks of diverse ages and locales.

There have been times in our history where there have been major events that saw tremendous changes in communities, but very few species disappeared. And there have been events where many species had disappeared and communities and ecosystems were barely affected at all.

Drew Muscente

And, while traditional computational methods can be used to classify samples into paleocommunities, they are best suited to datasets of a few hundred or thousand fossil collections. As a result of this limitation, traditional approaches can only be used on data from certain regions and time periods, rather than the full record.

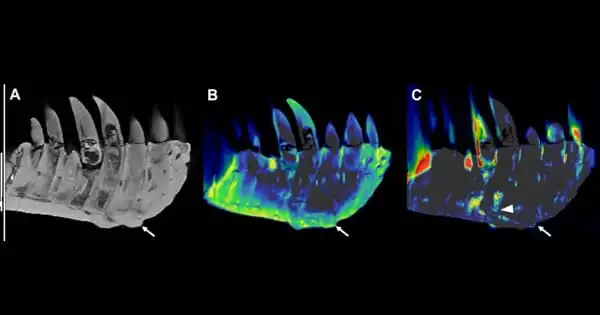

By using a community discovery technique based on network analysis methodologies, the researchers were able to overcome these obstacles and investigate the complete fossil record. These strategies are commonly used by social media businesses to connect people, but they are increasingly being used across a variety of scientific disciplines.

This is the first time, according to Muscente, that network analysis has been used to detect paleocommunities across the whole fossil record of marine animal life, from the beginning of time to the present geologic age.

Another advantage of the network analysis method, according to Matthew Clapham, a paleobiology professor at the University of California Santa Cruz who was not involved with the study, is the emphasis on displaying relationships rather than just the sorts of creatures present in an ecosystem.

“It brings the analysis closer to the way that the communities actually worked because communities and interactions between species are networks,” he said.

The program discovered more than 47 million relationships between these samples and categorized them into 3,937 separate paleocommunities using a database of 124,605 collections of marine animal fossils from throughout the world, representing 25,749 extant and extinct animal groups, or genera.

The research followed the evolution of communities and biodiversity over 541 million years. While both were affected by major extinction events, the degree of decline differed in some cases, according to the study.

Some extinctions had a greater impact on communities than on biodiversity. Some had a greater impact on biodiversity than on communities. And some people were impacted by both at the same time.

Furthermore, the researchers discovered no correlation between an extinction’s cause and whether it had a significant impact on communities or biodiversity.

The findings suggest that the ecological consequences of extinction are more dependent on which species are lost than on the quantity of species lost. Communities can be protected if the environment’s major participants are preserved. However, if too many of these players are removed, the community will fall apart as well.

Muscente expressed his optimism that the network analysis methodologies utilized in this study can be refined and applied to modern ecosystem research.

“I’d like to try and bridge the gap from the rock record to the present,” he said.

The study’s other co-authors include scientists at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the University of Idaho, the Carnegie Institution for Science, and Harvard University. The research was funded by the Keck Foundation, the Deep Carbon Observatory, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Carnegie Institution for Science, and the National Science Foundation.