For more than a century, paleontologists assumed that a fossil discovered in South Australia represented a powerful grave eagle (Taphaetus lacertosus). Now, new research has revealed its true taxonomy: it’s a vulture, and it’s the country’s first.

More than a century after it was first described as an eagle, Australia’s first fossil vulture has been confirmed. The discovery, made by palaeontology experts from Flinders University and the South Australian Museum, highlights the diversity of Australian megafauna and other animals many thousands of years ago during the Pleistocene period.

The renamed Cryptogyps lacertosus (meaning powerful hidden vulture) lived in Australia between 500 and 50 thousand years ago, according to a new study published today in Zootaxa.

“We’ve all seen a wedge-tailed eagle pick at a kangaroo carcass on the side of the road. Thousands of years ago, a very different bird would have filled the role of carrion consumer – one most people now associate with the African plains” Dr. Ellen Mather of the Flinders University Palaeontology research lab is the study’s lead author.

When we compared the fossil material to birds of prey from around the world, it was clear right away that this bird was not adapted to being a hunter, and thus was not a hawk or an eagle. The lower leg bone’s features are too underdeveloped to support the musculature required for prey killing.

Dr. Ellen Mather

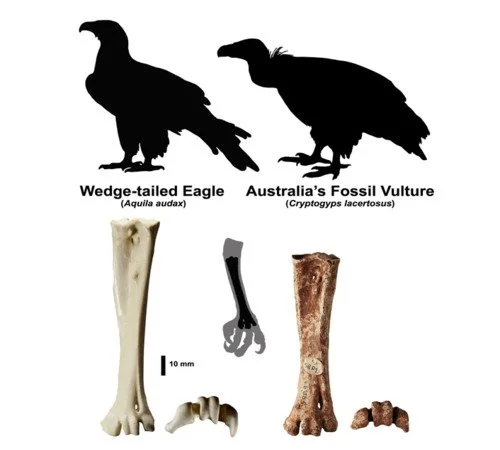

The extinct vulture shared the skies with wedge-tailed eagles, as well as enormous marsupial herbivores like Diprotodon and fierce carnivores like the marsupial lion Thylacoleo. However, unlike its similar-sized wedge-tailed cousin, the Cryptogyps was not an eagle; it was an ‘Old World’ vulture, a group previously unknown in Australia.

“When we compared the fossil material to birds of prey from around the world, it was clear right away that this bird was not adapted to being a hunter, and thus was not a hawk or an eagle,” Dr. Mather says. “The lower leg bone’s features are too underdeveloped to support the musculature required for prey killing.”

“When we placed Cryptogyps in an evolutionary tree, this confirmed our suspicions that the bird was a vulture, and we are very excited to finally publish on this species.”

First described in 1905 by Charles Walter de Vis, an energetic English ornithologist who described many taxa in quick succession while residing in Queensland, the fossil was first named Taphaetus lacertosus (powerful grave eagle).

According to senior author Flinders University Associate Professor Trevor Worthy, Cryptogyps lacertosus has now been given a new genus for what is a remarkable species. “The discovery answers the question of what happened to so many megafaunal carcasses when there were no vultures on the continent. We now know they were present. They’ve been concealed in plain sight “he claims

The lower leg bones, or tarsus, were especially important in revealing that this bird was a scavenger rather than a typical eagle. “This discovery also reveals that the diversity of our predatory birds used to be much greater. More importantly, the extinction of vultures in Australia has serious ecological consequences” Dr. Mather continues.

“Vultures play a very important role in ecosystems by accelerating the consumption of carcasses and reducing the spread of diseases. The loss of Cryptogyps could have caused a drastic upheaval in ecosystem function for a very long time as other species scrambled to fill in its niche.”

The first bone of Cryptogyps lacertosus, a fragment of a wing bone, was found near Kalamurina Homestead on the Warburton River in South Australia in 1901. De Vis believed it to be an extinct relative of the wedge-tailed eagle. It was only in the late 20th century that Australian palaeontologists began to suspect that this fossil material could belong to a vulture rather than an eagle.

Australia has the sobering distinction of being the only continent to have completely lost its vultures. Unfortunately, nearly half of all living vultures are threatened with extinction. The consequences of this decline have been disastrous, including increased disease transmission in both animal and human populations, potential impacts on the nutrient cycle, and ecosystem restructuring.

Dr. Mather confirmed the vulturine relationships when he linked newly discovered fossil material from the Wellington Caves in New South Wales and Leaena’s Breath Cave in Western Australia to the Kalamurina fossil.