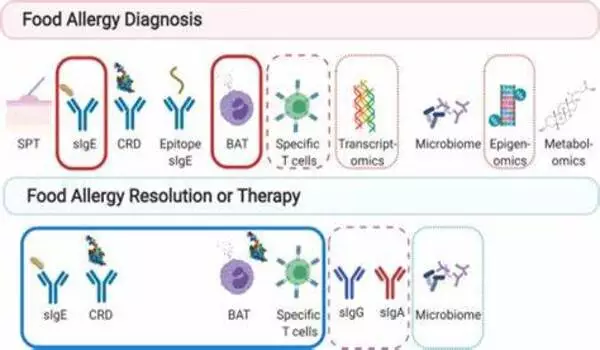

Researchers were looking into numerous areas of genetics, such as specific genes and genetic variants, in order to better understand their significance in food allergies. The notion was that certain genetic markers could make people more or less likely to have severe allergy reactions when they were exposed to specific dietary allergens.

For the first time, researchers showed that a genetic biomarker may be able to predict the severity of food allergy reactions. There is currently no reliable or easily accessible clinical biomarker that properly differentiates people with food allergies who are at risk for severe life-threatening reactions from those who have more mild symptoms.

For the first time, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago researchers and colleagues announced that a genetic biomarker may be able to assist in predicting the severity of food allergy reactions. There is currently no reliable or easily accessible clinical biomarker that properly differentiates people with food allergies who are at risk for severe life-threatening reactions from those who have more mild symptoms. The research was published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

“If the biomarker is detected, this may help us understand that the child is at a higher risk for a severe reaction or anaphylaxis from their food allergy and should use their epinephrine auto-injector if exposed to the allergen. Our findings also open the door to developing an entirely new treatment strategy for food allergies that would target or block α-tryptase.

Dr. Lang

Dr. Lang and colleagues discovered that the existence of an enzyme isoform known as -tryptase, which is encoded by the TPSAB1 gene, is associated with a higher prevalence of anaphylaxis or severe food reactions when compared to those without -tryptase.

“Determining whether or not a patient with food allergies has -tryptase can be done easily in clinical practice using a commercially available test to perform genetic sequencing from cheek swabs,” said lead author Abigail Lang, MD, MSc, an attending physician and researcher at Lurie Children’s Hospital and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“If the biomarker is detected, this may help us understand that the child is at a higher risk for a severe reaction or anaphylaxis from their food allergy and should use their epinephrine auto-injector if exposed to the allergen. Our findings also open the door to developing an entirely new treatment strategy for food allergies that would target or block α-tryptase. This is an exciting first step and more research is needed.”

While considerable progress has been made in identifying probable genetic markers linked to food allergies, it is important to highlight that genetics is a complex field, and several factors can contribute to the development and severity of food allergies. Genetics, environmental exposures, and the immune system’s response are among these influences.

Mast cells, which are white blood cells that are part of the immune system, contain the most tryptase. During allergic reactions, mast cells get activated. higher TPSAB1 copy number, which results in higher -tryptase, has previously been linked to severe reactions in adults with Hymenoptera venom allergy (or anaphylaxis after a bee sting).

Dr. Lang’s study comprised 119 TPSAB1 genotyping individuals, 82 from an observational food allergy cohort at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and 37 from a Lurie Children’s cohort who reacted to a peanut oral meal challenge.

“We need to validate our preliminary findings in a much larger study, but these initial results are promising,” Dr. Lang states. “We also still need a better understanding of why and how α-tryptase makes food allergy reactions more severe in order to pursue this avenue for potential treatment.”