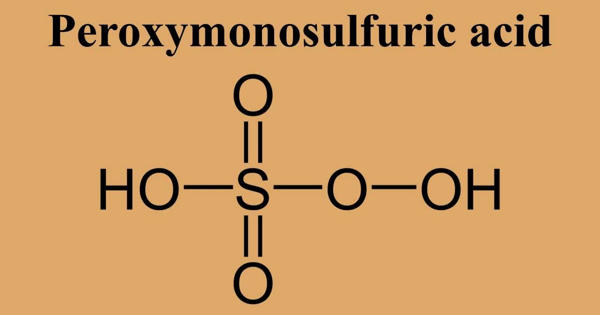

Ocean acidification is sometimes referred to as “climate change’s equally evil twin,” and for good reason: it is a significant and harmful result of excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that we don’t see or feel because it occurs underwater. At least one-quarter of the carbon dioxide (CO2) produced by the combustion of coal, oil, and gas does not remain in the atmosphere but dissolves in the ocean. Since the beginning of the industrial era, the ocean has absorbed approximately 525 billion tons of CO2 from the atmosphere, at a current rate of approximately 22 million tons per day.

Ocean acidification is a worldwide threat to the oceans, estuaries, and waterways. It is often referred to as “climate change’s evil twin,” and its prevalence is expected to rise as carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere remain at record highs. Ocean acidification and global warming, according to researchers from the University of Adelaide, are disrupting the way fish interact in groups.

“Fish exhibit gregarious behavior and cluster in shoals, which helps them acquire food and protect themselves from predators,” said project leader Professor Ivan Nagelkerken of the Environment Institute and Southern Seas Ecology Laboratories at the University of Adelaide. “Many gregarious tropical species are shifting poleward undercurrents of ocean warming and are interacting in new ways with fish in more temperate areas.”

We discovered that tropical and temperate fish species tend to move to the right when coordinating together in a shoal, especially when spooked by a predator. Under future climate conditions, mixed shoals of tropical and temperate species became less cohesive and showed slower escape responses from potential threats.

Angus Mitchell

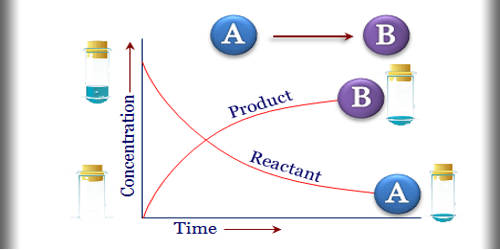

Under controlled laboratory conditions, the researchers examined how species interacted and behaved in novel ways as temperatures and acidification levels changed. The increasing concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere raises ocean surface temperatures and causes acidification. Although warming and acidification are two distinct phenomena, they interact to harm marine ecosystems.

Our oceans, like sponges, are absorbing increasing amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere. This exchange helps to regulate the planet’s atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, but it comes at a cost to the oceans and sea life, particularly commercially valuable shellfish such as oysters and clams. Ocean acidification is best known for its osteoporosis-like effects on shellfish, making it difficult for these creatures to build and maintain shells. Other species that are important to the marine ecosystem, such as reef-building corals and pteropods, are also affected by acidification (tiny snails eaten by numerous species such as fish and whales).

“We discovered that tropical and temperate fish species tend to move to the right when coordinating together in a shoal, especially when spooked by a predator,” said University of Adelaide Ph.D. student Angus Mitchell, who conducted the experiments.

“Under future climate conditions, mixed shoals of tropical and temperate species became less cohesive and showed slower escape responses from potential threats.”

Professor David Booth from the University of Technology, Sydney collaborated on the study.

“Our findings emphasize the direct effect of climate stressors on fish behavior, as well as the interaction with the indirect effects of new species interactions,” he said. The findings were published in the journal Global Change Biology by the research team.

“Strong shoal cohesion and coordinated movement affect a species’ survival: whether to acquire food or evade predators,” Professor Nagelkerken explained. “If the ability of fish to cooperate is harmed, it may determine the survival of specific species in the oceans of the future. When tropical species migrate to new temperate areas, they may fare poorly at first.”

The effects of disrupting what has been a relatively stable ocean environment for tens of millions of years are starting to emerge. Ocean acidification is literally changing the sea, threatening the fundamental chemical balance of ocean and coastal waters from pole to pole. Ocean acidification is sometimes referred to as “sea osteoporosis” for good reason. Ocean acidification can erode the minerals used by oysters, clams, lobsters, shrimp, coral reefs, and other marine life to build their shells and skeletons.

Human health is also an issue. Many harmful algal species produce more toxins and bloom faster in acidified waters in the laboratory. In the wild, a similar reaction could harm people who eat contaminated shellfish and sicken fish and marine mammals. While ocean acidification will not make seawater unsafe for swimming, it will disrupt the delicate balance of microscopic life found in every drop of seawater. Such changes have the potential to impact seafood supplies as well as the ocean’s ability to store pollutants, including future carbon emissions.